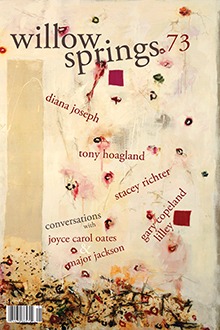

Found in Willow Springs 73

Back to Author Profile

A JEWISH WOMAN SHOULD BE modern, educated, and cosmopolitan; this will be signaled by the modern, educated, and cosmopolitan fragrance of Chanel No. 5, the scent of which permeates her body, all of her garments, her wig, and the entirety of her house, including the garage.

The epicenter of this womanhood should be located in the master bath. It should be large and sunny, with a marble tub, brass fixtures, and flocked wallpaper in shades of gold and cream. Pride of place will be given to a neat, gilt-edged dressing table holding powder, Fire and Ice lipstick, and a giant bottle of Chanel No. 5.

A woman should not keep such a bathroom all to herself! Little granddaughters are welcome to linger here, to breathe in the scent of toothpaste and soap while their toes sink into the wall-to-wall carpet. They are allowed to drink in the sight of the Dorothy Draper stools, the deflated wig on the stand, and the naked grandmother who hums as she picks out her clothes in the adjoining dressing room. She smiles and says, "Hello, Dolly."

"Dolly" is an acceptable endearment for a granddaughter, as is "Lovey." When angry or annoyed, she will call this granddaughter "Stacey."

A Jewish woman takes pride in her figure! She doesn't mind--or even notice--if her granddaughter stares while she funnels her long, dangling breasts up from her waist and packs them into the stiff, white cups of her Playtex bra.

A woman is married! She signs her checks Mrs. Max Siegel in exquisite, looping script long after Mr. Max Siegel has died. But everyone knows her as Eva.

A woman should be nicely dressed. Comfort-wear is acceptable for certain occasions, but one does not attire oneself in ragged, ill-fitting dresses. "Vintage" is not a fashion category a proper Jewish woman recognizes.

If the granddaughter is no longer so little, Eva will pat her hand and confide, "We're the only ones in the family with really nice figures." It will take the granddaughter a while to uncover the rule behind this statement: a Jewish woman should have big breasts.

A woman should be ladylike and proper, and she will despise any item, garment, or contraption that violates this rule. With spine-chilling fierceness she says, "Now Stacey, when are you going to get rid of that pickup truck?"

A woman should have ten perfectly manicured nails, unless she severs the tip of her pinky while unfolding the ping pong table; after that, she should have nine perfectly manicured nails.

She should have a lovely home! Deep-pile carpet, plush sofas, crystal chandeliers-her house should be suffused with Lawrence Welk-style elegance.

Her utterances should be bold and remembered: ''All the best books have lots of sex scenes," and, "I always thought Stacey would make a wonderful paralegal," and, ''Are you going to let her go out dressed like a washerwoman?"

Teabags must be reused. Every woman should find a special plate and designate it as a holding area for damp teabags.

A woman does not drive a truck! Not even a little red one! It doesn't matter if she's a student and moves every year. A Jewish woman pinches her granddaughter's elbow joint and says, "It's not feminine!"

Elegance is not to be confined to the master bath. Even the guest bathroom should be graced with framed tapestries and an alabaster tray holding shell-shaped soaps. Bathrooms are important! Her family was the first in Nephi to have indoor plumbing; her father insisted on it.

Bathrooms are a sign of cultivation! Certainly they were in Nephi, Utah, the small agricultural town where her father settled after emigrating from Grodno. Once he arrived in America, he never spoke his native Yiddish again. Not even to Bertha, his wife, who produced their first child, Eva, in 1906. Only English.

Well, they said schnorrer. They said mishegas and shmata.

She eats! She knows that life is composed of a series of meals--not too much, not too little. There's deep satisfaction in a nice piece of cold salmon.

After a meal, a woman should clean the kitchen until it looks like it's never been used. The sink should be wiped down with a paper towel, which should be placed on the edge to dry. Paper towels are to be reused.

When her granddaughter asks, "Why did your parents settle in Nephi?" a proper Jewish woman answers in an irritated, aggrieved tone that indicates that either: (1) everyone already knows all about this and therefore the question is stupid, or: (2) she doesn't want to talk about it, or: (3) she is so elderly that she no longer trusts her memory. She says, "Well, they had a store!"

This granddaughter has to ask other relatives and eventually consult the historical record in order to learn that her great-grandfather followed his elder brother to Utah. But the reason why two Jewish brothers would migrate from the Russian Pale of Settlement to the land of the Latter-day Saints remains hazy. One explanation is that they were fucking brilliant. But a proper Jewish woman would never say that.

Cars are important! Cars are the heraldry of the West--symbols of status and freedom and Eros. Max takes her for dozens of drives when they're courting, she reveals in her diary: "We went to our secret spot and parked!!!"

A Jewish woman is persistent! The battle over the pickup truck continues for a decade. On every visit, without fail, Eva brings up the subject of her granddaughter's truck. Her revulsion with it. Her deep desire for it to be jettisoned.

"Well! It just isn't done!"

A woman should not be an old maid. When her granddaughter is twenty-eight, she puts on an air of flinty resolve and says, "Now Stacey, when are you going to get married?"

A woman can be cosmopolitan even if she spends her entire life in Utah (with the exception of four years of college in Berkeley). First in Nephi, then, after she turns fourteen, in Salt Lake City. Her family moves there so Eva can meet some Jewish boys. Because in Nephi, they are the only Jews.

Well, she can meet a handful of boys: the Beehive State does not seem as enchanting to the chosen people as it does to others. In 1899, the estimated Jewish population of Utah is six thousand. In 2000, the estimated Jewish population of Utah is six thousand four hundred.

"Max wanted me to have it," she says, of her impossibly glamorous, entertaining-style house, with its shantung drapes and sunken living room and one bedroom (with a guest room in the basement). Still: one bedroom! Because Max built it as a love nest after the children were grown.

Max built it and promptly died. Eva lived there another forty-five years, alone.

A woman rarely mentions her dead husband, though she keeps his picture beside her bed, over the bar, and on the piano. On his side of the colossal master bath, his shirts still hang in the closet; beside the sink, his bottle of King's Men cologne remains until 2009, when Eva dies and her granddaughter relocates it to her own bathroom.

In 1919, her father trades in the horse for the car in which a Jewish woman travels past the houses and fields of her neighbors. These neighbors take the biblical verse about lost tribes very seriously and therefore approve of her family somewhat more than the other gentiles, gentile being their word for non-Mormons.

"Jeans only look good on a really slim woman."

She hums to herself constantly, happily, tunelessly. If asked what she's humming, she's elusive. If pressed, she says, "The old songs."

In Nephi, they are the only Jews the Saints have ever seen. And might ever see.

Flirting is always a good idea. A woman should not hesitate to bat her eyelashes and coo to her granddaughter's boyfriend, "Would you believe I'm ninety-eight years old?"

A woman should be wonderfully generous! Or perhaps wonderfully cunning. After once again informing her granddaughter of the deep hate she feels for the truck, she offers to take her down the hill and buy her a new car. Right now!

The granddaughter, who is fond of the truck, declines.

In the little side pocket of her handbag, a woman should always keep Kleenex, mints, and half a stick of Trident gum.

A proper Jewish woman gets on a plane and goes to every family event, every wedding and bar mitzvah and Seder. She looks very smart in her harbor-print suit and freshly curled wig at her granddaughter's college graduation, also from Berkeley. She does not say, "This all used to be a meadow full of sheep," until asked repeatedly. She is a creature of certainty; she does not like to talk about change.

In the side pocket of her handbag, the granddaughter--who is not a creature of certainty--always keeps Kleenex, mints, and a couple of Xanax.

A woman should keep an eye on the other women in the family. All of them should be properly attired and undeniably refined. A woman should make a good impression!

"Now Stacey, when are you going to get married?" With mounting horror, when her granddaughter is thirty-five.

The saints, at various times in history, are told to do business only with other Saints, but in Nephi the Mormons continue to patronize the store. One reason is that it's the only store. But everyone likes her mother, Bertha, who's so pretty and well spoken, her Yiddish accent notwithstanding. She went to college in Grodno, Eva says, though it's difficult to figure out precisely what this means since she left Poland at the age of eighteen.

A proper Jewish woman drives. When she is well into her nineties, she continues to drive to luncheons and weekly mahjong games. She runs her car through the carwash with startling frequency, though her current neighbors--mostly gentiles, as the Mormons continue to call the unaffiliated--seem unlikely to notice a muddy fender. Much less pass judgment on it.

There is a certain way of doing things and you do them that way. A cocktail buffet should include chilled salmon, cold cuts, and rye bread. Paper plates are for picnics, not parties. After years of witnessing this aplomb, the granddaughter finally adopts her grandmother as her personal domestic muse. When faced with hostessing conundrums, she ties on an apron and asks herself, "What would Eva do?"

The granddaughter does this without much seriousness, but also without much choice. As she gets older, she finds herself clutched by household furors, spasms of propriety tinged with unnamable feelings: tableclothpride and paperplatehorror, as the Germans might say if they didn't speak German.

A proper Jewish woman does not talk about who has died, or not often, though she does seem sad when all her friends predecease her. Which is what happens when she lives to be 103.

With utmost effort matched only by her pique, when she is one hundred and her granddaughter is forty-one: "It's not complicated. You get a rabbi, then go out to lunch."

The granddaughter never marries. She does not have children.

Perhaps Eva is embarrassed.

She dies at home, in her spacious, gold-and-white bedroom, beside a framed photo of Max, over a century after starting life in Nephi, a small, agricultural town eighty-five miles from Salt Lake City, where her family were the only Jews her neighbors had ever seen and probably ever would see.

So a woman must be neat, and friendly, and well spoken. She has to represent. Her entire people.

As the eldest child, Eva is up for the task--what luck! When her father expands into women's ready-to-wear, he selects exquisite things for her on buying trips: a gray worsted suit with a grosgrain tie, an emerald cape and matching silk shift. Even so meticulously attired, she will not enter the rooms of young men without a chaperone.

If pressed, a woman contributes to the oral history archive at the University of Utah. She reports that her mother Bertha left Poland "out of a sense of adventure, like any young person," though this view seems a bit sunny. Perhaps Bertha, educated as she was, noticed a few things--the Tsar's restrictions on Jewish settlement, for instance, and how the "temporary" May laws never ended. Later, her brother joins her in America. Her parents and three sisters remain in Grodno.

And presumably are slaughtered there.

"Where were your parents from?" her granddaughter asks. "The old country," she replies, because a woman does not like to dwell on the past. "But where, exactly?" "Oh," she says, and waves her hand toward the Great Salt Lake, dismissively.

In the living room, in a small, fancy cabinet, a woman keeps a clutch of cards and letters from the old country. The Yiddish words are unintelligible, and the ink has faded to the color of weak tea, but to hold one of these letters is to feel oneself balancing on the lip of something howling and vast.

A proper Jewish woman understands this. She understands all the sorrows. At times, knowledge flicks across her face like a crack in her gilt dressing table, but she never speaks of it. Instead, she escorts her granddaughters on a trip to Israel--four teenage girls and one seventy five-year-old, proper Jewish woman.

The green velvet cape with the fox fur collar and matching silk dress. The tiny chain mail purse. Oh dear, where are these lovely things now? Ah--they're in my closet.

After she dies, I find a dozen ancient, pristine matchbooks in her bathroom drawer. On the cover is an illustration of a woman in a crisp forties suit; on the inside it says: Join Hadassah, the Womens Zionist Organization of America. Identify yourself with a great human and historic endeavor! Which is what a woman does.

A woman looks forward. She looks for progress, for the good. She puts on neat clothes and straightens her wig. She's smart, upright, and feminine, and she tries to pass on the hard-earned rules that made her this way--the rules that made her safe. She represents, even when no one is looking, because she's the only Jewish woman these people have ever seen and may ever see.

She does not linger on the past, except for the old songs, which she hums constantly, handing them down through repetition and osmosis. She doesn't take things too seriously, except for the serious things, and she doesn't talk about those much. Instead she says, "I hate that truck."

It takes me a long time to understand what this means. But a Jewish woman knows things. She knows her granddaughter will eventually catch on.