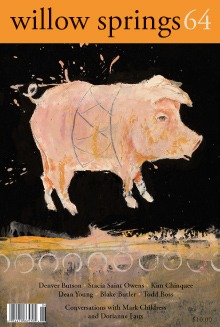

Found in Willow Springs 64

February 23, 2008

Rachel Kartz and Neal Peters

A CONVERSATION WITH MARK CHILDRESS

Photo Credit: alabamanewscenter.com

Born in Monroeville, Alabama, Mark Childress comes from a southern family and grew up in Ohio, Indiana, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama. Though he continues to move every four or five years, it is because he writes about the South, Childress says, that he is identified as a southern writer and often placed alongside Harper Lee, Flannery O’Connor, and Truman Capote. “On the one hand, it’s a kind of ghettoization,” he says. “On the other hand, it’s a really nice ghetto.”

Childress is the author of six novels, including Tender, a Literary Guild selection; Crazy in Alabama, published in eleven languages and named the [London] Spectator’s “Book of the Year” (1993); and his most recent, One Mississippi, of which Ann Lamott says, “Mark Childress is at the top of his form.” He has also written three children’s picture books, and his articles and reviews appear in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Times of London, and the San Francisco Chronicle, among other national and international publications. His awards include the Thomas Wolfe Award, the University of Alabama’s Distinguished Alumni Award, and the Alabama Library Association’s Writer of the Year.

After graduating from the University of Alabama, Childress worked as a journalist for ten years, until he eventually decided to focus all of his time on his own writing. He currently calls New York City home, where he is working on his seventh novel. We talked with him over coffee at Café Dolce in Spokane.

Rachel Kartz

One Mississippi takes place in the South, in the seventies, and explores the heightened racial conflict caused by the desegregation of public schools. In an earlier interview, you said you were in the South at this time but weren’t old enough to participate. Were you worried, when writing One Mississippi or Crazy in Alabama, about getting it right or possibly offending somebody with your take on these things?

Mark Childress

No, because what I’m trying to write is fiction. So I felt like as long as I was true to the spirit of the time and what happened then, and as long as I was honest in the way that fiction is honest, it’d be fine. It’s hard to say that a pack of lies, which is what a novel is, can be honest. But I truly believe that, in a lot of ways, fiction is more true than nonfiction because you can get inside people’s heads and tell what they really think. You can’t do that in nonfiction.

As a journalist I used to be frustrated that I couldn’t get people to say what their motivation was for something, even when I knew what their motivation was. People protect themselves. Novelists go right through that, to the heart of what characters really think.

Certain people criticized Crazy in Alabama because there’s a theory in civil rights literature that white people have to be the hero, that black people should never be the hero of their own narrative. This is the self-justified southern white way of saying, “We were really the good people.” I could never consider for a moment that Peejoe was the hero of the book. In fact, there’s a point where Peejoe says, “I’m not the hero.” His telling on the stand that the sheriff killed the boy is the one heroic thing he does, but it happens very late in the book. So, I didn’t set him up as a hero. I wanted a character that white people would be sympathetic to, a character that approached the racial conflict—see, to my mind, the sheriff is a human too. And he’s dealing with the forces of history pushing in the direction that he had to go. And I wanted to present the racial question in all of its subtlety. It’s not black and white. It’s all shades of gray. Just like every question.

Kartz

How much research do you conduct when writing about historical facts or people?

Childress

It depends. Tender was very much a novel of Elvis Presley. So, before writing that book, before I wrote one word of it, I read every book ever written about him, listened to every piece of music he ever made, which is a lot. I went to Graceland and worked as a tour guide. I toured all the homes where he lived, tracked down the addresses just to see what the settings were like. Then I started writing the book and I threw some of that away, changed things as I wanted to, because I wrote it as a novel. So, for that book, the research was critical. But I haven’t done research like that for any other book.

With V for Victor, I did go back and do a little research. Usually, I’ll write a first draft and look at the history of it and see what I need to check. Then I go back and maybe do some research, and change it on a subsequent draft. I don’t tend to do that much. One Mississippi was a different set of circumstances and actions, but a setting very much like the high school that I attended. I knew exactly what that library looked like, what the hallways smelled like, and what the cafeteria looked like. That’s pretty much just lifted from my life—the setting—though all the events are fictional.

Neal Peters

When writing about politically volatile material, like Peejoe’s experience in Crazy in Alabama, do you have a message you’re trying to deliver?

Childress

I think it was Louis B. Mayer who said, “If you want to send a message, send a telegram.” I really don’t think of my books as having messages when I’m writing them. When I go back and look at a book, I can say, “Okay, I suppose you could draw the lesson of A or B.” But when I’m writing a book, I’m actually just in the act of figuring out what happens, what people are going to do, and what they say, and trying to make it as interesting and dramatic as I can. It doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t stop and think if you’re sending the right message, but I think those reflections, like whether or not I was excusing white guilt, those are all things that arrive after you’ve published the book––those are critical reactions to the book. It’s not your concern when you’re writing it. You’re just trying to be true to the book’s internal rules.

Within Peejoe’s world, he doesn’t think of himself as a hero. The civil rights movement is set up as a story of villains and heroes. And there’s no room for gray areas—the media doesn’t describe gray areas—you’re either good or you’re bad. And so they chose which side he would be on. To me, one of the most interesting characters in that book is Uncle Dove. He’s much more like most people were in the South. He knows that racism and segregation are wrong, but he thinks it’s just too big for one man to change and it’s never going to change, so you have to kind of go with the flow and be kind to people as far as you can. And that explains what a lot of white southerners went through at the time.

The thing a lot of people miss, that I tried to explore in that book, is how close black and white people were before integration. Almost all white households had a black person working in the household. Even relatively poor families would have “help,” so the contact was a lot closer than it is now. In some ways, our society down there was more integrated than it is now. Not the public accommodations, not the pools and the restaurants and things like that, but everybody was in contact with everybody else. On a person-to-person basis, there wasn’t a lot of hatred. But there was a lot of interest on the white side of perpetuating the system that kept black people down.

Peters

Crazy in Alabama is written in varied points of view. Chapters alternate between Peejoe’s first-person point of view and Lucille’s third- person. Can you talk about the opportunities and limitations of using multiple points of view?

Childress

The thing I liked about opposing those points of view was that I wanted the story to have kind of a dark side and a light side and to go back and forth between the two. At times, Peejoe’s becomes the light story and Lucille’s becomes the dark story—they change places a few times. But I like a sense in the book that, Oh man, that was a heavy scene and Taylor’s dead, and that’s terrible, or, Okay we can relax because Lucille’s having a good time in Vegas. I like books that make you cry and laugh and that go back and forth between those extremes. I love John Irving’s books because he always does that. At the happiest moment in the book, you’re almost dreading what’s going to happen next, because you know it’s not all going to turn out to be so happy. And that’s so much more like real life than a story that’s all dark, or a story that’s all comedy. I kind of like that, giving the reader that sucker-punch, where it’s like I’m distracting the reader with something funny and then snap, something tragic happens. It happens that way in life. I like those contradictions and complexities.

As I get older my writing tends more toward linguistic simplicity, but more complexity of the narrative, if that makes sense. I think my style has become plainer on the page, and that’s been an intentional thing I’ve worked toward. A World Made of Fire is written in iambic pentameter—it’s extremely layered, there’s a lot of difficult dialect in it, and it’s a very challenging, “literary” kind of novel. At the time, I thought that was sort of the mark of art—to make something challenging and difficult and dense and layered and all that. I began to realize—and a lot of writers have written on this—that the harder thing to write is the simple sentence that expresses complexity. Or a story that’s accessible to a general reader yet has every layer of meaning of a literary novel. To me, that’s a bigger challenge, so it’s the kind of thing I like to take on because it’s the kind of book I like to read. You know, where the narrative grabs you and pulls you through. Dickens is somebody we study, but he’s also incredibly enjoyable to read. That’s the dividing line between the kind of books I like and the kind of books I don’t like—a book with a narrative that hooks me and drags me through it, and at the end, I go, Wow, I didn’t know that was going to happen. I love that effect in a book.

Kartz

What’s the difference between genre and literary fiction?

Childress

It keeps changing every year. When I was in college, it was the time of the metafictionalists and experimentalists, and Barth and Barthelme and Gass were the heroes of the teachers I had. Vonnegut. And these people were writing anti-novels and were all about subverting the form, changing the form, doing experiments and things like that. I didn’t respond to those kinds of writers. I read them and did my papers and discussed them, but I always preferred strong narrative. I was an addict for Dickens and books that have things that happen in them and things that change and people who are different by the end. It’s a strong narrative that draws me through.

That’s why I was so turned on by the Latin Americans. I discovered Marquez and Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes and all these great writers who were just as besotted with narrative as I was. Some of those books brought narrative back into fashion in North America. You can almost trace it. After One Hundred Years of Solitude, Mark Helprin wrote Winter’s Tale—which was a huge hit and was sort of a literary fabulist novel, a magic-realist novel set in New York—that sort of opened a lot of people’s eyes. They said, “Oh my God, we don’t have to write pinched little exercises in mental masturbation”—which is what some of that metafiction was to me. You can read every word of a Gass book and by the end of it, you may have learned something, but you haven’t felt anything. I like fiction that makes you feel.

That said though, the whole idea of genre, I mean, the idea of a “literary detective novel” didn’t exist twenty-five years ago. But even the great masters used to write them. Conrad wrote them. Twain wrote his. We got very uptight in the sixties and seventies about, you know, this is art, and this is commerce. And a book can’t be good if it’s popular. That’s as much crap as saying a book can’t be good if it’s unpopular. Popularity is no determinant of quality.

It also has a lot to do with shifting fashions. Narrative was not in style twenty-five years ago, and now it is. Now, oftentimes, you have books that have very strong narratives and are extremely popular. These two things used to be, could be, synonymous. But there was a kind of anti-commerce movement in the art. You know, Let’s throw out anyone who’s popular. And I’m glad to be part of the wave that’s brought it back the other way.

Peters

How do you think literary fashion will change in the near future?

Childress

I have no idea. Everyone in publishing has been predicting the end of publishing since I entered it twenty-five years ago, yet there are a lot more books being published and sold now than there were then. Everyone thought that the death of the independent bookstore would kill fiction and literature in America. The opposite has actually been true. I hate it as much as anybody––the death of the little independent bookstores in New York where I live. Now, all we have in our neighborhood is a Barnes & Noble. But on the other hand, in a typical small city in Alabama, there are now two Barnes & Noble stores with more books than that city had access to before. In a lot of small towns around the country, that’s replicated. In a Barnes & Noble, you have over five hundred thousand titles for sale. Before, maybe you had a mom and pop shop with six thousand titles. I’m sorry for ma and pa, but the people of that city now have an excellent bookstore. I kind of see it as a two-edged sword.

That said, the cell phone novel is coming from Japan. Have you heard of this? This is the rage now––they sell millions. They’re written to be read on cell phones. The modern generation––the ADD, caffeinated generation––will they have the attention span to read an eight hundred page novel? Seems to me enough of them will. Look at the list of bestselling literary fiction, fantastic books that are selling widely today. Everyone’s worried about the death of the physical book with these e-readers and Kindles from Amazon. I still say that until you can go to sleep on the thing, throw it across the room in a fit of rage, or tear a page out to write a grocery list, then regular books are going to survive. I still like to physically hold a book.

Peters

In your opinion, who is the best writer, or what is the best work of fiction, in the last twenty-five years?

Childress

Oh, wow, that’s an impossible question because literature is not a beauty contest. There’s not one person whose vision is better than everyone else’s. There’s a tendency, especially in America, to try to single out what’s the “best.” I have particular writers and particular genres that I go to over and over again. But I don’t rank them that way.

It’s very easy for me to say To Kill a Mockingbird is my favorite book because I was born in that town and it gives people something to talk about. But To Kill a Mockingbird was really my favorite book when I was thirteen or ten when I read it first. I haven’t read it in a long time so it’s not currently my favorite book. But, that said, I currently have a particular obsession with Latin American writers. I think Gabriel Garcia Marquez is probably one of the great writers of our time. One Hundred Years of Solitude is a seminal book for me that I go back to over and over again. You see Marquez’s footprints all over Gone for Good.

Usually, frankly, when I’m writing fiction, which is most of the time, I don’t read much fiction, because I tend to mimic what I read in my writing. I like to hear the way things sound. So if I’m reading a book by Jayne Anne Phillips, then the next page I write is somehow going to sound like Jayne Anne Phillips. Usually when I’m trying to write fiction, I read nonfiction or history or current events, then I save up novels. Then, when I’m in between writing, I’ll read a whole bunch of them at once.

Kartz

You were talking last night about Crazy in Alabama being a historical novel. What’s your definition of a historical novel?

Childress

A historical novel is a novel that takes place in the past, in which the fact that it takes place in the past is somehow central to it. I was telling the anecdote about the movie executive who said, “Yeah, I know it’s a civil rights story, but does it have to be period? Couldn’t we move it to today?” Because that would’ve cut the budget. And no, it couldn’t. Because the central concern of Crazy in Alabama is desegregation and the moment when desegregation actually happened in the little towns. When I wrote that book, I felt that there hadn’t been a novel that dealt specifically with that moment. Everyone thinks To Kill a Mockingbird is a civil rights novel, but it’s a novel about the thirties, way before the civil rights movement started, and at the end of the book, black people are no better off than they were at the beginning.

When I was a kid, that was that moment of demarcation. I remember very specifically coming back to the town where my grandmother’s house was. The year before we had swum all summer in the brand new swimming pool that had just been built. We came back the next year and they had filled it with blacktop. There was the diving board and the ladders that we used to get into the water and, one year after they built it, they had filled it with blacktop rather than let black people swim in it. I was seven years old that summer and that had a mighty big impression on me. It still doesn’t make any sense to me. That story was repeated all over the South that summer, because the public accommodations law was passed. Swimming pools were ruled public accommodations, so instead of letting black people swim, they just closed the pools. As a matter of fact, when we were scouting for the movie, we saw ten or fifteen pools that were still relics of that time. No one had ever swum in them again.

Peters

You move around a lot, never staying in one place for more than a few years, and yet, in some of your books—especially Crazy in Alabama—you explore social complexities against a backdrop of strong community ties. Do you, as a transient citizen, ever feel isolated from the communities you live in?

Childress

Absolutely. And I think in some way that may be why I move—to become a stranger again. That’s very much following the pattern that my family had when I grew up. My father had a job that transferred us every few years. It was like being in the army. We hated it as children, because we always had to leave our friends, and we were always the new guys in school, and just when things would be going good, you’d pick up and move and have to start all over again. But then, as adults, the three of us brothers have continued to move. Four or five years into a place and we say, “Well, I feel a little itchy now, it’s time to move on.” I think also that estrangement from the community is sort of what you seek as a writer. When you go to a place for the first time, you see things that people who have been living there for twenty years don’t see. It’s all new to you, the smells and the sounds and the kind of food and the way people talk. I still remember when I first moved to New York. It all seemed very powerful and exhausting and loud and busy and crowded. And now it’s just home. Trying to sleep without sirens going and garbage trucks at four in the morning, I’m like, I need some noise, it’s too quiet. When I start feeling too much at home in a place, then it’s time for me to leave. I think as I get older maybe that’s going to settle down. But, I don’t know, I haven’t seen much indication of that.

Kartz

Even though you keep moving, most of your books take place in the South. And you identify yourself as a southern writer—

Childress

I don’t identify myself as that, but everyone identifies me as that because most of the books I’ve written take place in the South. I come from a southern family. I’ve said being southern is like a virus––you carry it with you wherever you go. Just because you’re in Indiana doesn’t mean you’re not southern; it just means you go to the black side of town to find turnip greens. We carried our little southern household wherever we went, anywhere in the country. If I were from Kansas I’d probably be writing obsessively about Kansas. I wrote Gone for Good, which has nothing to do with the South, but its hero is a southerner, from Alabama and Louisiana. I just think of it as my country––my people—and that’s who I write about.

Actually, when I started, except for Truman Capote and Harper Lee, there really weren’t many fiction writers from Alabama. And now there are several really good younger writers coming up from there. I don’t think I had any effect on that, it’s just a generational thing. Living through the civil rights movement had a big impact not just on me but on the generation after me, the people who were younger than I was when it was going on. It continues to resonate. In the beginning, I felt like I was writing about a part of the country that no one else was writing about, because Truman Capote wasn’t writing about it anymore, and Harper Lee wasn’t. So I felt like it was my little territory. Now there are conferences on Alabama writing. That’s weird. That’s a new development in the last twenty-five years.

Peters

What does it mean to be a southern writer now?

Childress

A lot of times it means there’s a separate section in the bookstore, where they kind of ghettoize you—put you over to the side. African- American and gay and southern writing, these are ghettoized sometimes.

That’s the reason a lot of writers resist the label. If you come from the South, which is the most distinctive part of the country, you know you’re different. And the literature of the South is a different set of books than the literature of New York or California. But it’s kind of funny that nobody has conferences on midwestern writing and, in the South, there’s a conference every week on the question of, “Are we becoming too much like the rest of the country?” On the one hand, it’s a kind of ghettoization. On the other hand, it’s a really nice ghetto. Faulkner’s there, Harper Lee’s there, Flannery O’Connor’s there, Eudora Welty is there. Toni Morrison I count as a southern writer. Alice Walker’s there, Zora Neal Hurston. So, if you’re going to put me in a ghetto, I’ll take that ghetto. And I understand. Our culture’s all about subdividing us into little groups and trying to find which niche we fit in. Nobody ever considered Hemingway a Michigan writer, but if he were publishing now, he’d be considered some kind of provincial.

Kartz

You completed your undergraduate degree at the University of Alabama, but you didn’t pursue an MFA. Can you talk about the benefits and the drawbacks of not being in an MFA program?

Childress

The community I got into was journalism. I went to work for newspapers and magazines right out of school. For the next ten or twelve years, while I was writing my fiction at home, I was very much in a writing community—it was just a different kind of writing that we were doing. I feel like I wrote a million words for newspapers before I ever published a word of fiction. And I think each sentence I wrote—even if it was about a Gardendale city council meeting—was teaching me how to write. I do believe that writing is a combination of gift and craft, but I feel like practice makes you better. I think that I was a much better writer after ten years of working on deadlines and having to pump out whatever the editors told me to go cover that day. It took the ego out of the writing. You can’t have ego about your writing in a newspaper. You have a deadline. If you don’t turn the story in on time, you get fired. And that’s really motivating—to learn to sit in the chair and write.

I think sometimes in academia, inspiration is overplayed––that we have to find that moment for the muse to strike us. Well, bullshit. If you wait for the muse to strike you in the publishing business, you’re fired. Just because you’re a writer doesn’t mean you don’t have a certain duty to do your work.

The one thing about MFA programs, and that I regret I didn’t do, is read a lot. I mean I was reading, of course, all the time, but not in the way you do for school. When not in school, you tend to read more of what you like and you don’t always take on things that challenge you or that you feel are good for you. I needed to pay the bills some way and I thought that being a working writer was probably going to help me as much as doing fiction workshops. I had done four years of them at Alabama and they were great, but I kind of felt I had gotten all the juice out of them.

Kartz

You said in an interview that often your characters are much more in control of the story than you are. Nabokov said, “That trite little whimsy about characters getting out of hand; it is as old as quills. My characters are galley slaves.”

Childress

[Laughs.] Good for him.

Kartz

How do you reconcile these two statements?

Childress

Well, I didn’t make the Nabokov statement, so I don’t have to reconcile that. [Laughs.] He’s a hero of mine, and a brilliant writer, and I will guarantee you that when he started Lolita he didn’t know everything that was going to happen. Now, he would tell you that he made that happen and that he told those characters what to do. But I’d bet that, at some point, those characters became alive in his mind and were speaking dialogue to him––because that’s what they do.

When you really know a character, you know how he or she would say everything they might want to say. It’s kind of a semantic argument to say the characters did it. Of course, the characters are creations of your mind, so actually, your mind did it. I think it’s just a question of imagination. If you imagine the people to be real and you imagine them for long enough––an intense enough period of time––you come to know those imaginary people as real. And then they start doing things that you didn’t necessarily tell them to do. Now you have to give them permission to do those things. Maybe that’s what Nabokov was saying: they’re his galley slaves. If they took him in a direction he didn’t want to go, he would stop, go back and cut what he had just written and go off in another direction. So he’s definitely the captain of the ship, but I think those galley slaves sometimes grabbed hold of the rudder and steered him in a direction he didn’t think he was going.

Kartz

Regarding “Good Country People,” Flannery O’Connor said that when the wooden leg was stolen, she hadn’t known the character was going to do that, but in the end it was inevitable. Do you align more with that statement?

Childress

In my experience of writing, yes. But of course, I’m not Nabokov, so I can’t know what was going on in his head and the psychological somersaults he flipped to achieve what he put onto the page. But that sensation of Flannery’s is, to me, the sensation that I want––that sensation when I come to a moment in the story where something happens that I didn’t expect… and it seems perfect. That, to me, is the unconscious working through fiction. Some part of you prepared for that moment, but to the conscious part of your mind, it was not what you thought was going to happen.

In One Mississippi, I was about 180 pages into the first draft when I realized what was going to happen at the end. I’d had no idea. But when I went back and looked at the beginning, all the clues were already there. From the very first time you meet Tim, there’s something unsettling about him, something dark. I don’t know why I put that in there, but when I realized what was going to happen I stopped for about a month and said, I don’t want to write a book that ends with a school shooting. That was not what I had started to write. But that was what the characters did.

I don’t know if Flannery’s right or if Vlad is right, I just know that at that point, as hard as I tried to steer the galley slaves in another direction, they wanted to go where they wanted to go and I followed them. It’s a glorious moment when you’re writing a book and you reach that point where you feel like it’s telling you what’s going to happen. The story begins to write itself. That’s the moment where the writing becomes fun—instead of gutting it out to see what the hell you’re trying to do, which is what most of it’s like.

Kartz

The only two homosexuals in the novel––Tim and Eddie––kill themselves. Are you worried about the commentary this is making on homosexuality or homosexuality in the ’70s?

Childress

There were a couple others in there but you never quite realized who they were. For instance, if you read very carefully, the note that Tim left––it turns out that the guy he was at the rest stop with was Red. And there are a couple of other closeted characters that you have to go back and find for yourself. I understand that Tim and Eddie both commit suicide, and, I guess, in a way that’s a commentary on just how “nonexistent” homosexuality was in Mississippi in the 1970s.

There’s a wonderful memoir by Kevin Sessums, called Mississippi Sissy. He grew up the sissiest kid in some little Mississippi town. He went and had this whole gay life in Jackson in the ’70s, in the period of One Mississippi. I lived in Jackson in the ’70s, and, A: I didn’t know I was gay, B: I didn’t know any gay people, and C: I didn’t know there was a gay bar in Jackson, and I lived there. It was so completely closeted that unless you took that step you had no idea those people existed. It was a really different society, and I’ve read statistics that say, to this day, 30 to 40 percent of teenage suicides are closet homosexuals who can’t admit that they’re gay. And that’s now––when it’s so open. I didn’t set out or plan for those boys to meet that fate, but I think it was… God, if I tried to be out, in high school, in Mississippi? I probably would be dead in some way. I’d have either gotten killed or I’d have killed myself if I wasn’t able to pass as a “straight kid.” Some kids were just too sissy they couldn’t pass. A lot of them killed themselves or moved away.

I’ve definitely chosen, as an adult, to live in places that are a lot friendlier than that. I moved out of Alabama in 1987, and I’ve never lived there since, because I like to live in a freer place.

Tim, in One Mississippi, probably didn’t even know he was gay. Until, at some point, he had to admit to himself that A: he was, and B: he wasn’t going to change. I think that’s when he decided he’d just rather die. I hate the choice he made for himself.

Everyone says you can’t connect the gay experience with feminism, with civil rights, but it’s all the same thing—it’s all oppression and repression. I mean, you can’t pretend not to be a black person. That’s the only difference––everyone knows you are.

Peters

Crazy in Alabama later became a movie, for which you also wrote the screenplay. When you write a screenplay, what do you give up and what do you gain?

Childress

It’s a whole different medium and it was hard to learn how to do it. The studio sent me a box of scripts and the books they were based on. I spent two months reading the books and then the scripts. Some of them were great movies and some of them were really pulpy. I mean, how do you turn a Tom Clancy novel into The Hunt for Red October? I realized that the main thing you lose is like two-thirds of the story. Because if a movie’s as long as a novel, it’s going to be ten hours long. The first thing you start to think about is what to get rid of, what to throw out. And this is the reason that the book is almost always better than the movie—because the book is usually simply more than the movie. It’s more detailed, with more incidents––more complex, more subtle. If you made One Mississippi into a movie that had every flip and turn of the story, the thing would be twelve hours long and nobody would watch it.

So the first thing you have to do is stop being a novelist and become a screenwriter, which means you start looking for what you’re going to throw away. I had too many characters and too many stories going off in different directions. Then I had to look for the action that could be told in pictures. At the same time, as you’re losing a whole lot of story and you’re losing a whole lot of words, you’re gaining pictures. And so you can tell the whole story in a series of pictures.

There’s this scene in Crazy in Alabama I was proud of because I wrote it on the set like two days before we shot it. We were trying to look for a way to do that police riot at the swimming pool. A riot, by its very nature, is scattered. Something’s happening over here, and something over there. What is a visual image that could take us throughout it? And I came on the idea of focusing on the little brother of Taylor. You see him first. He’s watching the riot, then he climbs into the swimming pool and stretches out––the riot’s going on all around him. He’s just lying there, like Jesus lying in the water looking up. It said so much about the nobility of the soul of the people who were doing the protesting, and the evil going on around them. If you tried to describe that in a novel, it wouldn’t work. The words would just be spattering all around it. It’s such a simple image, that, to me, was the best moment of the movie because it was a visual distillation with no dialogue that in the book is seven pages.

I don’t know if you’ve read many film scripts, but they seem flat and the dialogue is very short. That’s because the actors and the set and the music and all this other stuff is added in to make it rich and full. That’s the hardest thing––to try to keep all that richness off the page of the script because that just distracts the director; he doesn’t need to know all that. He needs to know where they stand and what they say, and he’ll figure out the rest of it.

They’re both intriguing forms. I prefer the novel, because I get to be the director and the producer and the casting director; I don’t have to consult with anybody, and nobody can come in and cut my novel without my permission, or buy my characters. In a movie contract, they buy the right to your characters from now until the end of time—it’s stated—in any medium now existing or yet to be invented throughout the universe. And so I called my agent, and said, “I want Saturn. They can have all the other eight planets, but I’m hanging onto the Saturn rights.” He said, “That’s a deal killer.” I said, “Okay then forget it.” It’s ridiculous. They own your characters. So if they wanted to turn around and do “Crazy in Alabama 2,” and have Lucille become a black woman who moves to Detroit and works with Diana Ross—they have the perfect legal right to do it. In the novel world they can’t do that. I’m the author and I control it absolutely.

Kartz

You said once that when you’re writing novels, it’s like you’re seeing a film in your head—

Childress

We’re all poisoned by movies and television; we’ve had them since birth. I do tend to see scenes visually, and to see things in my mind, and then describe what I’m seeing in the scene. You have to use language that suggests all the senses. Not just what you see and hear, which is all a movie can do. In the book you can talk about how things taste, and how they smell and how they felt, and the temperature and all those things that are not accessible to a moviemaker. In the book, you can look at Lucille, and you can have your own picture in your mind of who she is. In a movie, it’s Melanie Griffith. So if you don’t like Melanie Griffith, you don’t like the movie. A book is a more universal thing, because your mind takes the place of all those other people that work on the movie. It fills in those gaps for you. That’s why one of the most exciting things to me is when a high school kid comes up and says, “God, it’s just like you’re a spy in our high school. That’s just what it’s like at our high school.” And then a seventy-year-old woman says, “Wow, that’s just like what it was like for me when I was in high school.” And you realize their experiences were completely different, but they projected their experiences onto yours and that’s got meaning that works for them. That’s the thing about fiction. That’s what fiction can do. I love that part.