Found in Willow Springs 57

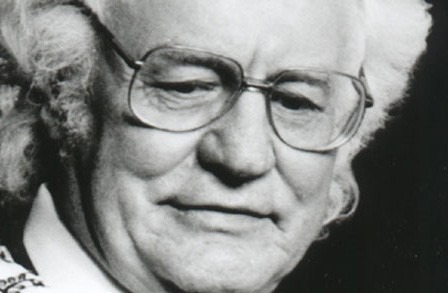

A Conversation with Robert Bly

Kaleen McCandless and Adam O'Connor Rodriguez

April 18, 2005

Photo Credit: Poetry Foundation

According to psychologist Robert Moore, “When the cultural and intellectual history of our time is written, Robert Bly will be recognized as the catalyst for a sweeping cultural revolution.” As a groundbreaking poet, editor, translator, storyteller, and father of what he has called “the expressive men’s movement,” Bly remains one of the significant American artists of the past half-century. In the following interview, Mr. Bly speaks about everything from poetics to politics, grief to greed, history to human nature. He ponders the death of culture and the redeeming nature of art, asking people to “develop the insanity of art, which is a positive insanity.”

Robert Bly was born in western Minnesota in 1926 to parents of Norwegian descent. After time in the Navy, he studied at Harvard and the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop alongside classmates that included Donald Hall, Adrienne Rich, Kenneth Koch, John Ashbery, W.D. Snodgrass, and Donald Justice. In 1956, he received a Fulbright to translate Norwegian poetry and discovered a number of major poets—among them Pablo Neruda, César Vallejo, Gunnar Ekelof, Georg Trakl, and Harry Martinson. He soon started The Fifties, a literary magazine for poetry translation in the United States, which eventually became The Sixties then The Seventies and introduced a new international aesthetic to American Poetry. He co-founded American Writers Against the Vietnam War in 1966, and when The Light Around the Body (1968) won the National Book Award, Bly contributed the prize money to the resistance.

While Iron John: A Book About Men (1990) was an international bestseller, Bly has published many books of poetry, essays, and translations, most recently Eating the Honey of Words: Selected Poems (1999), The Night Abraham Called to the Stars (2002), The Winged Energy of Delight: Selected Translations (2004), and The Insanity of Empire: A Book of Poems Against the Iraq War (2004). His most recent book of poems is My Sentence Was a Thousand Years of Joy.

We met Mr. Bly in his room at the Montvale Hotel in Spokane.

ADAM O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

Why did you decide to publish The Insanity of Empire yourself?

ROBERT BLY

Well, I have a publisher—HarperCollins—and one or two others that help, but I thought they’d take a year or more. And I decided, no, too important, try to get it out. And besides, I can do anything I want with it, like give them away if I want to. And I’ve printed a lot of books myself. It was just good expedience to get it out. A friend of mine designed the cover and the whole deal. It was done in two weeks.

KALEEN MCCANDLESS

In the first part of that book, the poems are really direct. Did you notice a change in the voice?

BLY

The first poems are the newest ones: “Call and Answer,” “Advice from the Geese,” and “Let Sympathy Pass.” [Reads from “Let Sympathy Pass.”]

People vote for what will harm them; everywhere

Borks and thieves, Bushes hung with union men.

Things are not well with us.

Well that’s true. It’s quite direct here. I had intended to do an entire book of eight line stanzas. But I couldn’t sustain it. So I went back to old notebooks and arranged them three at a time.

What was it we wanted the holy mountains,

The Black Hills, what did we want them for?

The two Bushes come. They say clearly they will

Make the rich richer, starve the homeless,

Tear down the schools, short-change the children,

And they are elected. Millions go to vote,

Vote to lose their houses, their pensions,

Lower their wages, bring themselves to dust.

All for the sake of whom? Oh you know—

That Secret Being, the old rapacious soul.

That “Secret Being” comes out of the Muslim world. The amazing idea they have contributed is the idea that inside you there’s a nafs—despite the “s”, it’s a singular noun—which is the greedy soul. I have a teacher in London, a Sufi from Iran, and he describes all that in The Psychology of Sufism. That whole little book is about the greedy soul. He says the greedy soul will eat up everything. It’ll destroy a hundred universes for the sake of a little attention—the flutter of an eyelash. It’s willing to destroy everything. When people become Sufis, they are thought that their primary enemy is the nafs. Occasionally the teacher checks to see how much progress they’ve made. I like the concept very much because it doesn’t put evil outside of us, with Satan. It doesn’t imply that a few little things are wrong with us, [in a gruff voice] “What do you mean a little thing? Are you insane?”

MCCANDLESS

Is that the same idea in Light Around the Body of the “inward self ” and the “outward self?”

BLY

That’s said more in the European way. The inward and the outward. I didn’t know about the nafs then.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

Is our nafs voting right now?

BLY

Everyone’s nafs together—they tend to be Republican.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

Automatically?

BLY

The Republicans, aren’t they the ones who stand and say, “Well, I want what’s mine. And I want what’s yours.” I’ve heard that voice before. In 19th century, the farmers of Kansas were fighters against lobbyists, the big grain companies, etc. Now Kansans vote Republican, even if that means they will lose their houses or businesses. The Republican Party does not represent the people, but the nafs. Forget about Franklin D. Roosevelt. Forget about Social Security. The greedy soul hates Social Security. “God, you’re doing something for someone else? Are you crazy?”

One of the things that drove Whitman crazy was to see the greedy soul at work after the Civil War. So many men died in that war. So many sacrifices were made. As soon as the war was over, the big companies moved in. The corruption was unbelievable. The lobbyists literally bought Congressmen. A positive vote in the House of Representatives cost $100. A Senator’s vote cost $500. That’s how visible the nafs was. Despair over that drove Mark Twain nuts. What we have now is a repetition of the situation after the Civil War, but on an international scale.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

Just add zeros to those numbers.

BLY

Exactly. [Reads from “The Stew of Discontents”]

What will you say of our recent adventure?

Some element, Dresdenized,

coated with Somme

Mud and flesh, entered, and all prayer was vain.

The Anglo-Saxon poets hear the whistle of the wild

Gander as it glides to the madman’s hand.

Spent uranium floats into children’s lungs.

All for the sake of whom? For him or her

Or it, the greedy one, the rapacious soul.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

There it is again. That same phrase at the end just like the poem before.

BLY

A few years ago I published a book of poems called Meditations on the Insatiable Soul. My father was dying at that time. I visited him and in two poems I describe my own rapacious soul. I called it then the insatiable soul, but I decided later that the phrase was too pretty—Meditations on the Insatiable Soul. The reality is not pretty. The word “greedy” is better. Anyway, the concept of the nafs is the main thing I’ve learned in the last ten years. The danger of giving poetry readings is that many people—as they did last night—stand up and clap. The greedy soul loves that. It’s great. And if it feels like it, the greedy soul will betray God, your children. You understand? Betray your wife. Betray your parents. It betrays anyone for the flutter of an eyelash.

MCCANDLESS

Is there a way to get away from the greedy soul?

BLY

The consciousness that there is such a thing helps. That awareness is what the greedy soul doesn’t want. You see? There are many references in the New Testament to the nafs. Jesus says, “When you pray, don’t pray in public.” Go into your closet and pray. If you pray in public, the greedy soul will eat the prayer. The Muslim holy books tell a story very like that: a community leader was so faithful as to prayer sessions, he always stood up praying in the front, and everyone thought that was so wonderful. He had done that for years. One day he came in late and had to stand in back. At that moment his nafs was irritated and complained to him. After that he never prayed in public again.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

Do you think the nafs is everyone’s primary motivation?

BLY

Ninety-nine percent of the time.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

Has that changed, do you think, over the years in America? I hate to be too focused on our country, but—

BLY

I think we are witnessing capitalism substituting itself for democracy. Democracy was always a touchy thing for the nafs because it offers something to black people, offers money to poor people. “Well, what do you mean you’re giving money to them!” When capitalism speaks, it says, “Everything is for the nafs. Period. We don’t care about the poor people in the world. We don’t care about anything but us.” Your nafs might advise you to give to the tsunami relief, because you might get a little flutter of the eyelash there. But you noticed how much was promised and how little delivered. The nafs says, “No, we’ll keep it for ourselves.”

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

The presidents on TV, they want some eyelid flutter, right?

BLY

Yes. Exactly. Being democratic would never do it for them now. Do you have my Abraham book here? Oh, here’s a good one. [Reads from “Noah Watching the Rain.”]

I never understood that abundance leads to war.

Nor that manyness is gasoline on the fire.

I never knew that the horseshoe longs for night.

In another poem I use the word “faithful”: [Reads from “The Storyteller’s Way.”]

It’s because the storytellers have been so faithful

That all these tales of infidelity come to light.

It’s the job of the faithful to evoke the unfaithful.

Our task is to eat sand, our task is to be sad—

Being sad is your task if you are fighting the nafs.

Our task is to eat sand, our task is to be sad,

Our task is to cook ashes, our task is to die.

The grasshopper’s way is the way of the faithful.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

You also said “our task is to be sad” last night, when you were talking about grief.

BLY

Several people noticed that. I did say that, yes, but the poem also says the reason I am not bitter is because I keep holding the grief pipe between my teeth. A friend says, “Everyone I know is trying to keep themselves from feeling grief.”

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

General grief? Personal grief? Both?

BLY

We were down looking at the river in Spokane. It’s polluted. The Russians come—there are, what, thousands of Russians in town, now—they fish there. They eat it. They’re not willing to accept the grief that we’ve polluted that damn river and the fish are inedible. That’s a kind of a grief we have to accept. More and more, we have to accept the grief not only about our history as a race of human beings, but also the grief of our race as Americans. And then at home you know, you see a little child and you are actually looking at a king of the nafs. “I want this! I want that!” You can’t do anything about it exactly, except to remember that you were like that when you were small and to feel a little grief for that. I think grief is the most valuable emotion we can have right now.

MCCANDLESS

You mentioned at the end of The Insanity of Empire that we have to process the grief, and if we don’t, we will be blind to our truth. You quoted Martín Prechtel—

BLY

He has a brilliant mind. We’ve been good friends. Maybe twenty years ago, a person from Santa Fe said to me: “There’s a strange man living in a teepee two miles out of town.” And I said, “Let’s go.” So we went, and there was Martín, just come from Guatemala, with his wife and two small sons. Later, I invited Martín to join a group of teachers at a men’s week in California. The teachers all got together and asked Martín what he would do with the men. Martín said, “Well, I think I would take the guys out into the woods and get them lost. They wouldn’t have any food for seventy-two hours.” Everyone’s eyes got big because they had been thinking about one hour sessions. Martín was talking about serious stuff—getting them lost in the woods! Alone for seventy-two hours! He is a great teacher and writer.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

I heard he recently started a school.

BLY

He’s always wanted a school. And he finally got it. And he loves to teach. He’s found an old Native American church building down there and every three months people come and spend maybe ten days to two weeks and he teaches them. He likes to start with Mongolia. There hasn’t been any teacher like Martín in this country for a long time. I’ll quote you one phrase of his. [Reads from The Insanity of Empire.] “Many observers have noticed that even though the United States and Canada have many resemblances, we have so many more murders per capita than Canada does. Why is that? Perhaps it’s because we kept slaves and later fought a vicious civil war to free or keep them. We know from Vietnam that the violence men witness or perform remains trapped in their bodies. Martín Prechtel has called that suffering ‘unmetabolized grief.’ To metabolize such grief would mean bringing the body slowly and gradually to absorb the grief into its own system, as it might some sort of poison.”

But this is like the people in the Civil War who did all that killing and the nafs approved of it. Very much. And then what did we do with them? We sent them away to kill the Indians. No one said to these soldiers at that time: “You’ve been in war, you’ve got to have three years of treatment before we let you look at one Native American.” [pauses, reads again] “Once the Civil War was over, soldiers on both sides simply took off their uniforms. Some went west and became the Indian fighters. We have the stupidity typical of a country that doesn’t realize what the killing in war can do to a human being.” That’s the same thing the President doesn’t understand today. [resumes reading] “When the violent grief is unmetabolized, it demands to be repeated. One could say that we now have a compulsion to repeat the killing.”

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

So what do soldiers do now?

BLY

You come home and beat up your wife, that’s the first thing you do. Then you start at your children. You cause an immense amount of damage. Unmetabolized grief is like an unmetabolized poison. Well, that’s a new idea. Psychologists have to take that in.

MCCANDLESS

Did we not have any kind of treatment in previous wars, like in World War II?

BLY

No. The ones who got treatment were the ones who had their legs blown off and stuff. And they’d be in the hospital. Otherwise, we’d turn them right back into the main culture. That’s hard to believe, but we did.

Researchers have identified a part of the brain called the amygdala. Apparently, horrible events get stored there. We know that for centuries people lived in groups of fifty or seventy-five. You might wake up at 4:00 in the morning and realize that strangers have come and killed twenty of your people. The dead are all lying around. Human beings cannot thrive then. It’s too much. The speculation is that the memories of what you just saw, all those dead people, your relatives and friends, are stored in the amygdala. Within two days everyone is back to normal and thinking, “I don’t really remember what happened.”

We could say that Civil War soldiers stored violence they had done and seen in the amygdala. Then when they went West, and fought Indians, it came out of the amygdala.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

Is there anything to be hopeful for?

BLY

I don’t know, that’s your problem. [everyone laughs] But I have a friend out here who works a lot helping farmers. He also built up this section of Spokane, about five years ago. And now he does all kinds of things, but he says that he has a hopeful place in him that he always keeps and he won’t allow it to be disturbed. At the same time, to be able to feel all the grief. Not to have it—the whole mind stuns, you don’t feel anything, it’s not that. You feel the grief that you have, and then you make sure that you have hopeful places. And that’s one thing that poetry does. If you get through a poem, I don’t care how much grief there is in a poem, at the end you’ll feel some hope. And that’s what poetry is. It’s a form of dance. And oftentimes—because you start dancing in a poem, I mean the vowels dance and the rhythm dances—by the end, your body receives an infusion of hope. More than it does from prose.

MCCANDLESS

Why’s that?

BLY

Because it’s a compressed form, so in order to make it lively, it has to have dance. The difference between poetry and prose, I think, is that in poetry, there are old, old ways of dancing with the vowels, consonants. And if you can’t dance, you can’t write poetry. Every time one reads Rilke, we see that he talks about the most serious things, but there’s always a feeling of great delight at the end. He’s a genius. So’s Kabir. We should put one of his poems in here.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

Did you translate his book?

BLY

Yes. [Reads from “The Great Communion of Being” by Kabir.]

Inside this clay jug there are canyons and pine mountains

and the maker of canyons

and pine mountains!

All seven oceans are inside, and hundreds of millions of stars.

The acid that tests gold is there, and the one who judges jewels.

And the music from the strings no one touches, and the source of all water.

If you want the truth, I will tell you the truth:

Friend, listen: the God whom I love is inside.

Whew! That should be enough, huh? [Reads from “The Meeting” by Kabir.]

When my friend is away from me, I am depressed;

nothing in the daylight delights me,

sleep at night gives no rest,

who can I tell about this?

The night is dark, and long hours go by

because I am alone, I sit up suddenly,

fear goes through me

Kabir says: Listen, my friend,

there is one thing in the world that satisfies,

and that is a meeting with the Guest.

So, you can say that this exhilaration is the very opposite of the mood around the nafs. Kabir says that inside you there is an energy which is never cruel and always luminous. That’s the source of hope, and that’s why a saint will go out in the desert and spend twenty years, because sooner or later, that Guest will come along.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

What did you say at the reading, about “The poet who really writes, standing there after you die?” I believe the poet’s last name was Jiménez—

BLY

Oh, yes. “I am not I.” That’s right. That’s the mood. [Quotes “I am not I” by Juan Ramón Jiménez]

I am not I. I am this one

Walking beside me whom I do not see,

Whom at times I manage to visit,

And at other times I forget.

The one who remains silent when I talk,

The one who forgives, sweet, when I hate,

The one who takes a walk when I am indoors,

The one who will remain standing when I die.

It’s a great poem. He puts all he knows of “The Visitor” in one poem. “The one who remains silent while I talk.” So, as long as we talk so much, we can’t feel “The Visitor” to be present. “The Visitor” is the one who “forgives, sweet, when I hate.” The one “who takes a walk when I am indoors.” He’s pointing out the association of that secret one with nature. “The one who takes a walk when I am indoors. The one who will remain standing when I die.” I love this poem.

MCCANDLESS

Yesterday, you said something about the transparency of nature. Can you talk about that a little?

BLY

Maybe I could read you “Watering the Horse.”

How strange to think of giving up all ambition.

Suddenly I see with such clear eyes

The white flake of snow

That has just fallen in the horse’s mane!

There is something here that reminds us of some old Chinese poets. Once they had given up the idea of joining the Chinese Social Service, they’d drop out of ordinary life and become hobos. That was an aim of the sixties, too. Gary Snyder, for example, did that deliberately, knowing well that whole Chinese background. The idea is: “I’m not going to be a part of this. I’m just going to go out and build a little shack instead.” Then a strange thing sometimes happened: you would be able to see things in nature much more clearly. It was as if nature became transparent.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

Did it actually work that way?

BLY

Yes.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

Your poems that EWU Press just published: were these written in that Chinese mode, too?

BLY

Exactly. I wrote them in the late fifties and early sixties. It happened that I didn’t publish them at the time. So I went back one day and found them. I love that kind of poem. They aim somehow to catch the transparency of nature.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

What do you mean by “the transparency?”

BLY

Okay. [Reads from “After Working”]

After many strange thoughts,

Thoughts of distant harbors, and new life,

I came in and found the moonlight lying in the room.

Outside it covers the trees like pure sound,

The sound of tower bells, or of water moving under the ice,

The sound of the deaf hearing through the bones of their heads.

We know the road; as the moonlight

Lifts everything, so in a night like this

The road goes on ahead, it is all clear.

The transparency suggests that we know the road. You long for something? You can do it. We know the road. I like that. You almost never feel that certainty in the city, but you feel it out in the country. I’m a very coarse person in many ways. You can see all these greedinesses in me and my passions. And my body is heavy. And yet, because I try to hold on to that transparency, my body has to put up with it.

One time, St. Francis and his friends were coming back from Rome, and they didn’t have much money. They walked and walked, and it was cold and raining. Finally they got to the house of friends. They knocked on the door, “Let us in!” “What are you robbers doing down there?” And someone threw hot water on them. “No, it’s Francis. It’s Francis and his friends! Let us in!” “Go away you robbers!” They dropped stones on them and trash. “Come on, let us in! It’s Francis!” And the people keep throwing stuff on them. And the people with Francis say, “This is terrible!” “No,” Francis said, “This is perfect joy.” You understand? Because all of that was good for defeating their nafs. They think they’re really something and these guys are throwing stuff on them.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

Sometimes when you read, you come back to a poem that maybe you haven’t read in a while, and you seem genuinely surprised by something you said?

BLY

Maybe it’s good I have a bad memory. I was surprised last night when the man who introduced me asked me to read “The Hockey Poem.” “The Hockey Poem” isn’t transparent at all, it’s just funny. It’s about greed of various kinds. But I was surprised at how many jokes there were in it. I enjoyed that. And here is a nafs sentence about the goalie: [Reads from “The Hockey Poem.”]

This goalie with his mask is a woman weeping over the children

of men, who are cut down like grass, gulls standing with cold

feet on ice. And at the end, she is still waiting, brushing away

the leaves, waiting for the new children, developed by speed,

by war….

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

What about madness—that’s something from the reading. You said we have to double the madness. You were talking about television and children—

BLY

The insanity of television is really ugly insanity. It’s shameless nafs insanity. We have children, and we let the television teach them? That’s insane. As a parent, it’s important to develop the insanity of art, which is a positive insanity, to meet that negative insanity. Because we had many kinds of art in the house, the positive insanity of art, the children were not quite as caught up with the other stuff. What I’m trying to say here is that parents have a new responsibility now. We used to be able to trust what was coming in. You can’t trust it anymore.

MCCANDLESS

Do you think kids are turning away from books?

BLY

Yes, of course. The figures of the percentage of children who read dropped from 60% in the last decade down to 50%, and now it’s down to 42%. And that’s in only about five or ten years. [pauses] Do you read to your children?

MCCANDLESS

I read to them every night.

BLY

That’s because you’re intelligent. Kids know there’s fun in that. My kids did, too. But we’re talking about developing “throw-aways.” We’re developing a culture that accepts the idea that three-quarters of children will be throw-aways, only good for buying cars and houses. And we’re not going to educate them, and we’re not going to tell them about God. We’re going to use them as throw-aways, to buy the things people manufacture. That’s ugly.

MCCANDLESS

The ultimate nafs civilization, isn’t it?

BLY

Yes, it is. This nafs-life is not what the United States was created for. So, we’re in some kind of trance in which we see these hideous things happening to our children and we don’t do anything about it. The nafs in television has a big hold on adults too.

MCCANDLESS

Is that a recent development, or was it apparent in other media before television?

BLY

You had to go out to see movies. Now, it’s right in the house. It’s sort of like having whores in the living room. Why not make the kitchen into a whorehouse—how would that be? We used to leave the house to see something really shoddy.

I don’t understand how we’re going to solve this, because we’ve trained human beings to be passive. Don’t walk, drive a car. Don’t make your food, buy it. That works for capitalism. Most Senators and Representatives have been bought by the corporations.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

Then why even keep a place of hope?

BLY

Hope is what combats it. If you have hope, you pick up the book, turn off the TV. You’ve got to have hope for your children. Because that’s what it’s for. It’s feeding, you’ve got to feed them that hope. And that’s a divine thing that parents do.

MCCANDLESS

And cry when they don’t. Is it a primal thing in everyone, that has always been, or do we traditionally have a “counter-nafs?”

BLY

Joe Campbell told a story about that. He was living in Hawaii, and one day policemen saw a man who was about to jump over a cliff. The two policemen got out of their car. One policeman stepped over—it was very risky—and when the man jumped, he reached and caught him. And Joe said, “He risked his life to save the life of that other man. That’s what culture is.” The willingness to die for another is the opposite of the nafs.

O’CONNOR RODRIGUEZ

You said at the reading that as you become more interested in culture, America moves away from it—

BLY

That fits along with the way we are becoming a nafs culture. If you really took on the obligation to help every human being in the serious way a Catholic nun takes her vow, you would be much more resistant to the wholesale lowering of human standards through television and buying presidents. I think it is built into the human being—this anti-nafs willingness to sacrifice oneself for another human being. Women do that whenever they give birth. I think that’s one reason men are more nafsish—women sacrifice every time they have a child. The nafs culture doesn’t support good motherhood.

MCCANDLESS

Do you think we’re exporting that to other countries?

BLY

I do, and that’s horrifying. Norway and Sweden, for instance, resist our ways. Sweden has wonderful laws for the protection of pregnant women, whether they’re married or not. They put a lot of money into that. Of course, here that would be knocked down by Tom DeLay. It’s interesting to think that since The United States has become the world leader in encouraging nafsish behavior and selfishness in all forms, we can’t expect a culture of serious book reading to continue, because it’s hard work. Students now are primarily visual; people graduate high school and college and they don’t read. Something infinitely important is being lost. Reading requires great effort. Observers tell the story of a grown man, an illiterate who decided to learn to read. It turned out he had to put blanket over himself eventually when he was reading because his body temperature actually fell two degrees from the effort. In the West, children start early, so we don’t recognize it, but it shows how much energy is required to take these little squiggles and turn them into thoughts and ideas. Reading requires a lot from the body. When kids don’t read, they’re losing something infinitely important. It isn’t only that we’ve become visual. We’re losing what we’ve spent a thousand years, two thousand years learning how to do.