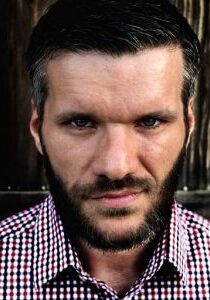

About Laurie Lamon

Laurie Lamon’s poems have appeared in journals and magazines, including The Atlantic Monthly,The New Republic, Ploughshares, Colorado Review, Arts & Letters Journal of Contemporary Culture, Poetry Northwest and 180 More Extraordinary Poems for Ordinary Days, edited by Billy Collins. She was selected by Donald Hall, Poet Laureate 2007, as a Witter Bynner Fellow for 2007. Her collections of poems are The Fork Without Hunger, 2005, and Without Wings, 2009 (CavanKerry Press). She is a professor of English at Whitworth University.

A Profile of the Author

Notes on Four Poems

“This Poem Doesn’t Care That It Isn’t a Sonnet” is a very new poem, and it’s representative of other elements of style and subject in my work. I’m very concerned with what distracts us from the on-the-ground reality being played out everywhere around us. The poem is a kind of catalogue of what a poem knows it can’t do anything about: the superficial distractions of pop culture, technology’s interference with real human time, political terrors, human suffering, animal abuse… It acknowledges that we live with burdens which are overwhelming. On one important level, our responsibility is simply to be aware, to be witnesses, and to care. At the more “political” level, the poem is curious about the world, engaged by facts, and accurate in its telling. Even at a quieter lyrical level, the poem also quickens us. To be truly affected by beauty is not a passive response. It wakens our desire for the conditions and goodness of that beauty.

The question of stylistic and subject connection and departure is so interesting to contemplate and study in poets. I began as most poets probably do, being startled and gratified by imagery, and how a line has architecture, enacting time and space. Thirty years later, I can see how early affinities have evolved into recognizable themes. Some of those are evident in these four poems.

I wrote “Pain Thinks of Black” over fifteen years ago. I remember the process of writing it distinctly, probably more distinctly than any other of the Pain Poems, certainly. These poems are quite different from my other poems. With this series, and crucially with this poem, I am trying, with very intentional reductions, to render experience without metaphor or simile, without the values of association and correspondence. That sounds like a description for something other than a poem! When I was writing the first of what would become over 40 of what are now The Pain Poems, it was the X-ray and MRI image that became the visual guide for what I was handling. Everything familiar to me as poetic tools had become inadequate.

“Pain Thinks of Black” took years to get right, as ridiculous as that sounds. It’s only 4 lines long! The utter catastrophe that can open up, be real, and become part of your life’s history, and which you can survive…. Dickinson’s poem “Pain—has an Element of Blank—“ and her descriptions elsewhere of “Adamant” are buried in the psyche of this poem. “Pain Thinks of Still Life” is something quite different in subject, exploring the paradox of that genre to express the dynamic of possibility that the image and juxtaposition can render. The imagistic poem, the Still Life painting—they offer an amazing presentness that is anything but quiet.

Notes on Reading

I read all kinds of books. I love history and science and biography. One of the best books I’ve read in the last few years is Walter Isaacson’s Einstein: His Life and Universe. I think curiosity about the physical world is an antidote to most of our failings as human beings! Emily Dickinson knew much about botany; she was a devoted and learned gardener, and she grew orchids in her conservatory. Poets I return to again and again include Dickinson, Adrienne Rich (An Atlas of the Difficult World in particular), and Muriel Rukeyser. I didn’t discover Rukeyser until graduate school, and I can’t imagine understanding Rich’s poetry without knowing hers, and her biography. I read Czeslaw Milosz to encounter one of the most generous, compassionate, and intelligent minds of the last century. I think “Six Lectures in Verse” should be required reading for us all. I read Linda Pastan for her spare complexities, and for the way she integrates mythology into the world of streets and flower markets, husbands and breakfast tables, overcoats and bedsheets.

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.