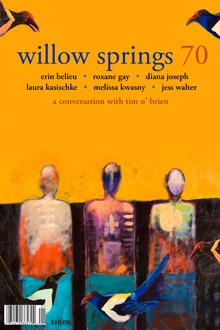

“Through the Womb” by Roxane Gay

WHEN WE FIRST MET he told me how much he loves children. He told me how much he loves women because they can bear children. Motherhood, he said, is the truest expression of a woman; a woman is not really a woman until she bears children. The way to his heart is not through the stomach, but through the womb. He doesn’t know there was once fruit in my womb that spoiled. He doesn’t know they hollowed me out. He doesn’t ask and I don’t tell. I let him talk. I mete out rope, inch by inch. One of us will hang. Once, while we were drinking wine, I asked, “But what about women who can’t have children? What about women who tried and things ended badly?” A look of perfect disgust crossed his face. I admired the honesty. He said, “Women like that are invisible to me.” Then he smiled, said we would make pretty babies. I refilled my glass. I smiled back, even though he could not see me. I said, “Yes, baby.” He would like me to find the way to his heart through my womb. I went to the bathroom and tried to find my reflection in the mirror. The edges were blurry. I was startled. I collect these moments–the sorrows, the petty betrayals of my body. I worry them between my fingers like stones until they are bright and smooth. I use these bright smooth stones to cover my rage, the hollowness of it, to weigh it down, to hold it close, to weigh me down. I cook him dinner and watch him eat. Sometimes, he grunts his appreciation, asks for more and I bring it to him. I say, “Eat, baby.” I place one of my stones on the tip of my tongue. I satisfy myself with the blandness of it. Whatever he asks for, I give him. I want to fatten him until he is all flesh. I make sure his beer is cold or his martini stiff. He offers to wash the dishes, but I say, “Why don’t you go sit on the couch?” I say, “Tell me about your day.” I say, “Tell me everything you’ve ever wanted to say.” I do these things so my resentment stays sharp and pure. He likes to sit on the couch stretching his legs. He unbuttons his pants and lifts his shirt, exposing his pale stomach. There is a slight bulge from the food he’s just eaten. He slaps his belly and it echoes because my home is sparsely furnished. He says, “Look at my baby bump.” I say, “Yes, baby.” He says, “Feel it kick.” I say, “Yes, baby.” Sometimes, when we’re in bed, he says, “If you get pregnant, we’ll have to get married.” He says, “Let’s have at least five kids.” He suggests names. I say, “Yes, baby.” He is hopeful when he says these things. He touches me with purpose. We take chances. I should say, he takes chances. In the heat of the moment he sometimes uses the word breed as if I am livestock. I am an animal. He is an animal. I am a bitch in heat. We rut. When I am late, he says, “Maybe you shouldn’t drink that glass of wine, just in case.” He says, “Maybe you should take a test.” I say, “Yes, baby.” I let him run to the drugstore and while he’s gone, I pour myself a glass of wine. I call him on his cellphone and say, “Bring pickles.” I am a spiteful woman. I carry my stones. They grow heavier with his hope. They are cold. I name them—Greta, for a girl, Edgar, for a boy. His mother is in a convalescent home. We visit her on Wednesdays and Sundays. She pretends to forget my name every single time, always looks at me as if my features have changed. Her eyes make me uncomfortable. They are cloudy, the blue irises seeping past their edges into the white meat of her eyeballs. When his phone rings, he leaves his mother’s room, always talking too loudly. He has no respect for the quiet of slow, lonely death. I sit in an uncomfortable chair with wooden arms. I try to breathe shallow. The smell of the place is terrible. His mother licks her lips. They are dry and the sound makes me cringe. She asks for water and I pour some into a plastic cup from a plastic pitcher. Her hands shake when she drinks. Sometimes she needs help so I stand next to her and hold my palm to the back of her head. I hold the cup in my other hand and bring it to her lips. She takes careful sips. If he sees this, he says, “You are so beautiful when you’re being maternal.” I say, “Yes, baby.” He only sees me when he wants to. I worry more smooth stones–how he sees right through me, the chilly numbness when he touches me. I nearly worry the skin from my fingers, imagine nothing left but blood and bone. Once in a while, a nurse’s aide breezes through the room to shift the arrangement of air molecules. She smells like cigarette smoke. All the nurse’s aides sit out behind the convalescent home, smoking their way through their shifts. He is an only child, born when his mother was forty-two, an unexpected surprise. She likes to tell me, “There’s still time for you.” She thinks I’m waiting. I am much younger than she thinks. There is too much time for me. When he leaves the room to talk too loudly on his phone, he’s talking to the woman who thinks she’s his girlfriend, who doesn’t know where he spends his nights, or knows and doesn’t care. I have no idea what I am doing. They have a child together, a girl, she’s three. I pretend not to know her name. “I’ll always feel something for the mother of my child,” he says, and I say, “Yes, baby.” Sometimes, I see his girlfriend at the grocery store with her daughter. The kid looks like him, the same brown eyes, the same strange walk, toes pointing slightly inward, an extra bounce in the heel. The girlfriend is not as pretty as me, though her child is beautiful. The girlfriend wears loose clothing, often pants with block letters across the ass. She is much younger. Her hair is wild. She is radiant. She always smiles. She and her daughter walk through the store. The girl talks as much as her father, filling the store with chatter. She seems precocious. Precocious children can be irritating. Intelligence in a child is a delicate, dangerous thing. I like to follow them. I am invisible so they can’t see me. I close my fist around my stones so they do not rattle. I follow the girlfriend and her daughter and make note of what the girlfriend buys to feed her child. I judge. I think, I would not feed my child such things. Sometimes the girlfriend and daughter are leaving the convalescent home as we arrive. When we walk past each other, she doesn’t see me. She holds her head high. I do too. When he spends the night, which is often, I make him breakfast. He likes three-egg omelets, runny, so the eggs fold around his fork as he eats. While I cook, he stands behind me, resting his chin against my neck. He rubs my stomach and sways our bodies side to side as I add cheese, fresh mushrooms, green peppers, and fold the omelet in half He says, “Some day, it won’t be just us.” I flip the omelet, then slide it onto a plate with fresh orange slices and parsley. I fatten him. I say, “Yes, baby.” I watch him eat. I keep his coffee hot. As he eats he nods happily, reads the paper. He asks, “Why don’t you ever eat?” I never answer and he quickly forgets his question. I close my hand around a bright smooth stone, the weight of it growing heavier and heavier, holding me to this place. I press my fingers against my ribs, skin thin, and feel my sharp, hollow bones.