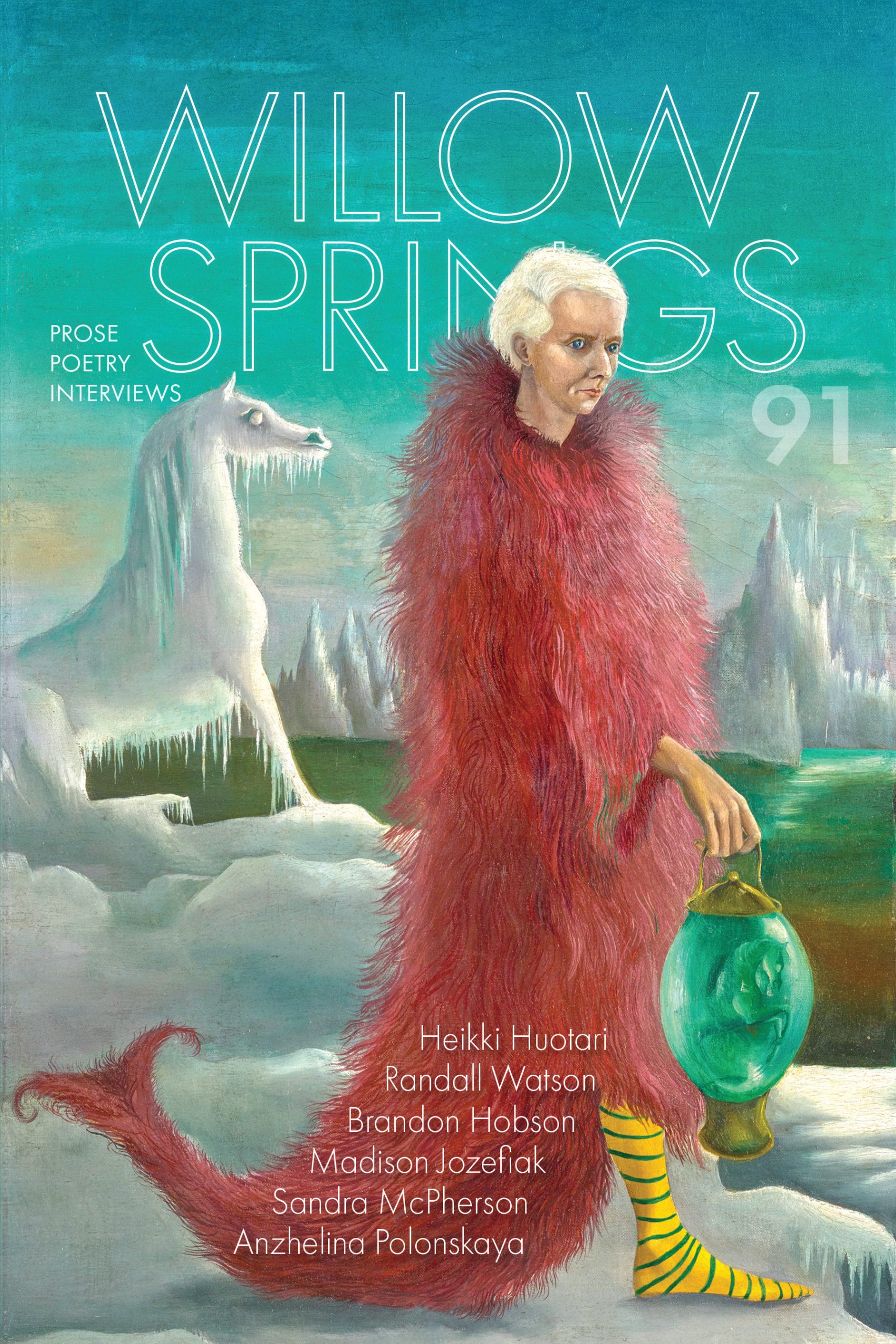

Found in Willow Springs 91

Back to Author Profile

THE VILLAGE. There was a time before the plantation cleared a road to the village when we were known as the ancestral keepers of the fern grotto. It was a charge borne upon our ancestors by the king, his private spiritual retreat, he proclaimed in a moment of dominion as he clapped the shoulder of the one nearest to him, and thus was born our village. Though the king and the promise of his return were long dead, his decree was ferried from generation to generation until the arrival of the mercantilists with their high white collars and long black coats waving papers of deed and oleaginous promises of stewardship. So we said nothing when they built their sugar mill at water’s edge at the mouth of the cove, stayed silent when they stripped half the grotto’s lee side to build the flumes and winches to bring materials up and down to the mill, and watched the seas while we bided our time.

THE BOY. The night before the boy was born, the mother couldn’t sleep. Whether, she said, it was the discomfort of her first pregnancy or from her failure to garner for the boy a karmic destiny, she didn’t know. Habit more than thought moved her body to shore’s edge once again this night. There she saw the cobalt-colored sea writhing like a live thing, a serpent splitting itself upon the sand, and when she got close enough, she saw that the waves were not the iridescent reflection of the gibbous moon and her mantle of nightly attendants but swell upon swell of butterfly wings winking like wet sapphires in the water, yielding for a moment on the black sand before returning to the roiling surf. She touched nothing but ingested the vision before her with a concentration fierce enough to pierce the awareness of her unborn son and returned to her hut to give birth.

WINGS AND WAVES. There are those who are eager to jump in at this point to offer the naturalist explanation, namely, that a wreck of cliff-dwelling kittiwakes must have descended upon a kaleidoscope of migrating butterflies and with ruthless efficiency, denuded their prey of their gaudy and undigestible finery for the fat-storing soft bodies within. We wait for them to finish explaining before nodding and secretly side-eyeing each other for the pity we feel for their circumscribed lives.

THE GROTTO. How long the sugar mill remained, whether it was a couple of years as some say or only a couple of months as say others, all agree that the ocean will reclaim what is hers. So when the tsunami punished our island, drawing itself up into the depths of the grotto before retreating with every vestige of structure man-made, everything scrubbed clean down to the concrete piers, we were not surprised. We returned to the grotto, cleaning and replanting, plunging it back into its fecund darkness so the ferns would grace us with their return.

THE CARPENTER. It was at this time the carpenter came to us. He had been abandoned by the company, cast-off, much like their dream of wealth by sugar cane on the shores of our village. So, like the shipwrecked sailors throughout the ages who had found our village by happenstance and luck, the carpenter settled himself on the edge of our village and became the latest curiosity for the boy and the other village children, another gift from the bountiful largess of the sea.

BLESSINGS. Looking back, it is tempting to see these as the salad days, the time just before the events that would mark us forever, like stigmata of our village existence. The village children were growing strong and brown under the tutelage of a watchful ocean and an unyielding sun. The time when the carpenter took it upon himself to build a fence around the area we had been using as a makeshift cemetery, so that now and into the future, our beloved dead could lie free from the scourge of stray dogs. And we, so impressed by this improvement, sent word to have the ground officially consecrated, only to wait several years before an irritated cleric, who must have been diverted from a more important sacred duty elsewhere, arrived in a rattling hackney pulled by the whitest horses we had ever seen, spat out a few perfunctory words in a language we did not understand, and did not even stay for the celebration we had

prepared but left immediately afterward without a word, which fostered a lingering resentment that still poisons that realm and would explain the hodgepodge of memorials strewn across that space without line or reason as if left to the dead to organize themselves.

THE FIRST TIME. When it happened, we were sure it must have been a mistake. It was easy to see why. The boy was not yet a teenager, although the local authorities had declared he was dead, and two days later even the good doctor had come to the village bearing an official certificate with a penned signature in a Continental blue-black ink that was said to contain a kind of iron integrity that would make it permanent for all time. The children pretended to play across from the carpenter’s shop while he silently pieced together the small cabinet that looked less like a casket than a coracle rabbeted with a tightness that made us believe it could have been seaworthy. It displayed the parsimonious dovetailing, which eliminated the need for nails but of a type that you won’t find today even among the most skilled artisans except in the dreams of certain old men with calloused pads on the tips of their fingers and along the fringes of their sunken palms like the underside of a bear paw. The next day we all followed the family through the heat of the dusty flats to the cemetery and stayed to watch our friend be lowered into the dry hole and then withdrew back to our homes that evening to suffer the ministrations of our grandmothers who had resurrected rituals they had learned from their grandmothers when they were children to ward off the evil eye. None of the parents believed them when the children complained late that night of being unable to sleep because of the incessant moaning that apparently only they could hear, like the lamentation of an ancient tree slowly keeling over in repose.

LAZAR. Blinded by frustration and bound together by the injustice of their insensate elders, the children spurned the warmth of their beds and stumbled out into the darkness like dazed homunculi to the source of that sound, pulled like a beacon to the graveside where they had stood earlier that day. The creaking was unbearable here, so they dug with their hands in the fine-grain dirt to expose the coffin of their friend, which bulged and groaned like the leathery egg of some mythical creature about to burst forth. Suddenly branches, torn from nearby trees by the more quick-thinking among them, were passed around and they started to beat that coffin in a wild cadence, less to silence the fulsome creaking than as another improvisation to accompany this festive event. At some point, their drumming must have cracked the lid, for it broke into several pieces and fell into the coffin. For a moment there was complete silence, a stillness like the eye of a hurricane, save for the labored exhalations like a thirsty animal emanating from the darkness within the coffin. In a slant of moonlight that cleared some cloud cover just at that moment, like a heavenly beam from the eye of God himself, they saw a pair of hands grip the gunwales of the casket, and the boy who had been declared officially dead, certified, and borne to his grave, pushed himself up until he stood looking up at them

unblinkingly, his face awash in light.

Drownings are always tricky things, is all the authorities would say.

Children, the doctor was reported to have said with a shrug. Such miraculous healers.

THE CELEBRATION. We all accepted it for what it was: a cosmic mistake, a wrinkle in the timeline of fate, and among the more religious among us, a divine correction and rebuke of the greedy reach of the evil one. The boy’s mother celebrated by pinning the death certificate to the wall of their hut where it could be mocked and insulted by all who entered for their homecoming feast to honor the boy who had escaped from that most unjustified of deaths—drowning—and somehow slipped fate to return to them. The boy, however, seemed mostly unmoved by the festivities as he sat at his place of honor and turned a placid face toward all of us, silently scanning us like a scientist observing the sacred rituals of a heretofore unknown tribe. But what did we expect? Who knew what he must have experienced in the anteroom of the hereafter? Would any of us have acted any different if we had been wrested from the grip of death?

THE GIRL. Then it happened again. This time there were no special sounds, no churning in the minds or bodies of the children; in fact, the most remarkable thing about it was how pedestrian it was, how it lacked any sort of imprimatur, spiritual or otherwise. She just appeared suddenly along the main path of the village, as lost and confused about it as we were. She was grown certainly, but still in the first blush of womanhood, wearing what looked to us like the homemade shift of another era. And yet, when we tried to talk to her, tried to wheedle out a name at least, she looked at us with the mild alarm of one who was hearing only gibberish. It was only the oldest women in the village, those who still retained the vestiges of the indigenous mother tongue spoken in their youth before the advent of Christian education, it was only they who were able to reach the young woman and learn that she indeed did belong to us, but from that earlier time when things in the area were not yet named, and in legend her name had been given to the pali that overlooked our nearby beach, the suicide of a girl who threw herself off the promontory after her inevitable jilting by the sailor who had taken her heart, her body, and in the end, her very reason for living. Apocrypha made manifest in unshod feet.

MORE. They took her in, just as we took in the others who started returning, some like the girl, rambling into the village until they were recognized, and others, like the boy, who needed assistance to escape the confines of what was supposed to be their domicile of eternal rest. At first, the Japanese and those who cremated out of tradition or financial necessity feared they had made an irreversible error, inadvertently choosing an immovable roadblock on the road to restoration, but we found that even the incorporeal ashes of the cremated were enough to generate the return of a loved one or family member.

QUESTIONS WE POSED, ANSWERS WE EARNED. It soon became apparent to all of us that there was no explanation for who came back and who didn’t. Victims of crime or violence, those who, it could be said, to have suffered unjust deaths, did not automatically return. Those who gave their lives for service or principle, what we had been taught were honorable deaths, rarely returned. Suicides, those who might be said to be undeserving of life, were given another chance. Those who perished through accident with surprise in their eyes did sometimes return but arrived with a joyless demeanor. To this day, those of us who were children wonder why none of our pets ever came back. Over the days and weeks, one hard lesson did become clear: Despite what we had been taught, the way one died garnered no judgement. Death, unmoored from the moral reasoning that we had willingly accepted into our minds and bodies as smoothly as a knife between the ribs, was as meaningless as the stone guardians that marked our temples. If our final acts on earth were merely the treading of thespians in some forgotten production, then even the one thing we thought was absolute, death’s finality, was just a cawing mockery of the pitiful scaffolding of belief that had shaped our existence.

THE RISEN. Those who returned were different than we had remembered. They arrived with a taciturn demeanor and a deportment of extreme indifference that we previously had ascribed to heartless ranchers or plantation managers. The risen gazed upon us with an inscrutable flatness in their eyes, which belied the overwhelming sense of melancholy in their wake that suffocated us when they left the room. While the chill of death had left their bodies, it seemed that no warmth could be gleaned from them, wives who in previous times remembered reaching for the warmth of their husbands in bed, now complained of heat being leeched from their bodies and replaced with a glacial coldness lonelier than their annulled widowhood. Some reported feeling smothered by a murderous rage if one stood too close to them, while others disagreed and called it a bottomless anguish that constricted their lungs and hearts. No one could disagree that too long in the presence of one of the risen brought on a curious vertigo whose main symptom seemed to be the keen awareness of the lethargy of time, as if the inertia of the past was suddenly made manifest in the moment and we were forced to grievously confront it in the hidden consciences of our souls.

LUCK, THE ONE-EYED BITCH. Superstition kept us from probing too deeply into the ‘why’ of our luck, for surely that would make it cease overnight, but we could not help wondering about the ‘who.’ Who decided who would return? Perhaps if there had been some sort of plan, some discernable method we could have intuited to answer this critical question, maybe we would have been happier. But in the vacuum created by that absence, whispers grew louder that some families got more than others. Abusive husbands returned without invitation, mothers who died in childbirth returned without their babies, even village drunks and a hated overseer came back to remind us of painful memories and other bad times. Some began to claim that all the risen were addled, clearly damaged goods not good enough for heaven nor hardy enough for hell. But that only generated other recriminations. Suddenly, personal insults and buried grudges bloomed in our village to poison neighbors and drench relatives in the bad blood of long dormant feuds, all of which gave jealousy leverage to fray the bonds of our community. A gloom settled itself as tight as a fist in our village. Sparks between neighbors could ignite from mere sideways glances, welcome parties were scarcely attended, and family members shunned each other like carriers of incurable diseases. All might have remained this way with the ruts of hatred and habit growing deeper in our hearts, and envy burrowing itself further under our skins only to erupt later in a froth of anger and accusations, were it not for the quake.

THE QUAKE. The island’s uneasy existence between the crust of its former self where we lived and the nascent flows where lava and sea met to form the wet black husk of new birth produced the occasional rumbling: the restless goddess of earthly creation reminding us of her power. And while the rest of us cowered beneath tables or benches, or braced ourselves in doorways or against walls, the risen, all of them, were outside looking to the heavens watching the passage of birds as they lifted themselves from their aeries and rookeries and took wing away from their volatile surroundings. It only occurred to us then that maybe they hadn’t wanted to return either. That all of us were victims of some cruel cosmic joke, punchlines in an internecine squabble between unfeeling gods, or the detritus of a forgotten divine prank. While the risen were still silently beseeching the heavens, a murmuration swept through the village, and all of us concluded the thing that seemed obvious at the time: we needed to find them a way back.

BLOOD IS THICKER. The suggestion that we kill them again was quickly extinguished as less a solution and more of a genocide. Besides which, the responsibility for each would fall to their family, something no one could contemplate. Subsequent discussions only offered solutions that were no less messy, no less violent, nor any more feasible. The adults were stumped until a child pointed out that weren’t we just trying to bring them all closer to heaven? She then pointed to the highest peak on the island.

STAY OR AWAY. Preparations began immediately for what in earlier days might have seemed like a celebration. Meals were prepared and packed, water was drawn from catchments into flasks, fruit was harvested for snacks on the way up, and even the littlest ones grew giddy. Everyone, outfitted and loaded up, filed out of the village with our risen. To say that we were joyous would be an aggrandizement, rather a tendril of hope, something that had been missing among us for a long time, seemed to rope all of us together. As we neared the summit, the children started singing the song that they had pieced together on the way up:

Here we come, here we come, here we come,

To the top of the rising sun!

We‘ll bring them all the way,

For all to stay or away!

FAREWELLS. Nearly everything that had been prepared—the food, the water, the small and sundry gifts we had collected—were all left on the perimeter while we gathered the risen in the middle. We explained to them that the sun will soon set and the moon will soon rise, and then added, in case they had forgotten, the traditional time for farewells. With only the simplest of goodbyes—a touch of the hand, perhaps, or a stroke of the cheek—we turned to go back down the mountain. Those who dared to look back saw the gathered look after us for a moment and then return their gaze back up to the heavens, and then we knew that it was time to go.

THAT NIGHT. All through the village, it was a solemn dinner as we tried to restrict our conversation to the barest of necessities and concentrate on the mundane movements of our lives. We carefully avoided any glimpse of the mountains and what might be silhouetted there in the moonlight. That night we slept like the dead, immovable in our guilt, yet freed from the yoke of sorrow that we had borne since their arrival.

THE SUN ALSO RISES. It was with a sense of disappointment, rather than surprise, when we awoke the next morning to see a few of them back in the village, seeming no different than when they had left the day before. Throughout that evening and on into the week, all of them would eventually return to us with no sign of fear, recrimination, or anger in their eyes or in the corners of their mouths. Just a tacit acceptance on both sides, like an indifferent handshake, of the return of the status quo.

A NEW THEOLOGY. We gathered, then, to discuss that perhaps we had been mistaken in our theology. The dogma honed within us by the church, namely, a universal lust for heaven, had been erroneous. What other conclusion could there be from the actions of the risen? We did not need the naïve exhortations of a clergy who were as neophytic as we were in this circumstance. Faced with our bleak rejection of the ascension into heaven, we were left with only with the descent into hell.

HELL WITHOUT FIRE. We immediately recognized the deficiency of our catechism. Our religious education spends a lifetime preparing us for heaven with nary a motion for the preparation of hell. A suggestion of fire was timidly raised, only to be extinguished by the silence of that ghastly imagining. In our bifurcated cosmology, if there is a stairway to heaven, wasn’t there also a pathway to hell? The long silence evoked by that question threatened to transmogrify into grief, when again, a child spoke and reminded us of the forbidden hollows that formed the vascular core of the island.

BASALT. This time, we packed no food, prepared no gifts, and packed only a fiasco of water for each of the risen and a single torch for all as we coursed out of the village and turned toward the black fields of pāhoehoe lava. The eons of magma that slowly passed out of the core to create our islands had cooled over epochs to form spacious voids others called lava tubes. To us, this arterial array was a monolithic account of creation, each ropy wall beneath the surface a testimony to the nascent delivery of our island. We chose the longest tube we knew, a subterranean hollow of singular opening with a deep and lengthy passage within a surround of darkness. We formed a gauntlet and after handing the boy the torch, we ushered him and the rest of the risen into the maw of dead lava, as if welcoming them into their new dwelling. They ambled forward, one following another while we watched from the surface until the torchlight no longer refracted back to us. We turned then to the scree that surrounded us and stacked basalt over the entrance to create a seal and a ward to our problem.

A BEACON. No one is sure if it was the boy who returned first or not, but it was sometime that evening that someone saw the torch braced against the cemetery fence, like a beacon for the prodigal, and, as some of us took it, a fiery admonishment of our lack of imagination. It would be by noon the next day when all the risen had returned and the first raindrops started to fall, sizzling in the flare of the torch before succumbing to the downpour and being snuffed out.

THEN CAME DAYS OF RAIN. The singing of the birds replaced by the incessant keening of male frogs in their splendor and libidinous desire. Evacuated graves like neglected basins overflowing. A flourishing of centipedes with weary mothers as sentries over their sleeping children at night. Versicolor scale like mold murals blooming in corners and beside windows. All of us standing in open doorways, brooding on terrestrial desolation. Loneliness like hookworm through the soles of our feet, creeping up our spines into our heads.

THE CARPENTER. For weeks, each raindrop struck us like the ticking of an eternal clock while the earth drowned in ennui. Lulled by this, we failed to notice when the carpenter began, only that at some later point, we realized that he was the only moving thing in the torrent. We watched him move deliberately, stacking the wood, and then racking it to keep it above the continual drift that coursed through the paths in the village. More days were taken up by sawing, measuring, arranging, shaping pieces for a

plan visible only in his head. They fit together slowly under the blows of his hammer, first a bulging side like a herniated wall, then a couple of generous platforms, forward and aft, but it wasn’t until he shaped an enormous fin on the underside of his creation, did we realize that he was creating a keel for a vessel with an extraordinary draft. On the day he started applying the pitch, the day we heard the first bird sing and saw a rift in the gloom like the hesitant cracking of a door before a flood of light, we knew it wouldn’t be long before we had to be ready to try again.

SHEPHERDS. Again this time, there were no elaborate preparations, no planning or thoughts of contingencies, just a quiet gathering of the risen by the village women, while the men hauled the boat to the ocean. The children, rather than high-stepping and clowning around like the first time, entered the gathering and silently took the hand of the one they liked best and led them like gentle shepherds, while the risen walked with a relieved acquiescence, toward the beach. Once there, the mother of the boy had only to gesture and the boy climbed up onto the vessel and ascended to the highest point on the prow. The village children then released the hand of their charges and the risen climbed wordlessly into the boat, none of them looking back once they entered the craft, but like the boy, kept their eyes focused forward to the horizon. When the last of them was aboard, the men in the water timed the shore break, and through a wrangling of shoves and precise nudges, they propelled the boat forward where it eventually caught and launched itself out into that enigmatic blue expanse. None of us went home then. Instead, we continued to watch the shadow of the boat against the setting sun until the nadir of the earth’s curvature swallowed them up. In later years, we would remember this moment as the start of an unraveling inside ourselves, a blurring of boundaries in the meaning of time, the notion of sorrow, and the comfort of death, but at that moment, all we understood was that we were suddenly alone again, forsaken in the twilight.