“Sin-Tra-La!” by Diane Lefer

My FATHER HAD BEEN DEAD going on four years when his widow phoned from Portugal.

“I’m sure you don’t want to talk to me,” she said, “but I need to know where you live these days. I’m sending you something I never should have kept.”

I was still in the same apartment in Santa Monica. She had kept everything.

What Olive shipped to California was my father’s disinterred remains.

The coffin was made of heavy and beautiful wood with brass ornamentation. It took four somber men to bring it in. What is the etiquette for this? The men seemed surprised when I reached out to shake their gloved hands.

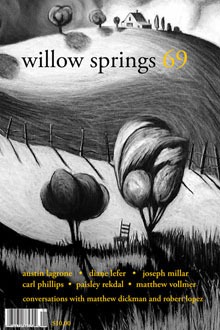

OLIVE AND I HAVE NEVER MET. She’s apparently what’s referred to as an “English Rose,” though from her name and my distaste for her I’ve always imagined a sickly greenish tinge to her skin. I wasn’t invited to the wedding. I’d never been to their home in Sintra. When Dad and I talked via Skype, from what I could see of his expat study, it looked lugubrious-no other word for it-though I realize the gloomy shadows behind him might have been due to the webcam. The city itself? In the album Dad posted, Sintra glows all pink and gold, magical geometries and crenellated towers. It looks ancient and unreal as a folktale and it was hard to imagine my rational father there. A professor of sociology, he had deprecated his own field, calling it “common sense with footnotes,” but in our time apart, who knew how much he had changed? My plans for a visit were postponed again and again, usually at Olive’s request. So I looked at photos and tried to picture my father walking steep hills past churches that resembled fortresses-buildings that didn’t point the way to heaven, I thought, but were built to confine the faithful and hold them in.

I did not attend his funeral. I didn’t even know he had died till Olive sent me an e-mail with a link to her Flickr photos from the wake and the mausoleum in Lisbon, and so it was easy to believe he wasn’t really dead. He was in Sintra, far away, retired amid the palaces, on perpetual vacation. But the fact remained that I was an orphan, both parents gone now, an existential state of being that should reverberate in a person’s soul. And it didn’t. I’d been deprived of the immediate shock of his heart attack, of keeping vigil till the moment he died. If you don’t know you’ve been orphaned, if your life goes on, unruffled, if you only find out after the fact, it seems histrionic to feel what you feel. I sent Olive an angry e-mail.

She replied with equal anger: “For you, death is a hobby. I am in mourning and I did not want or need your morbid attentions.”

I DON’T KNOW what sort of service Olive arranged in Portugal, but she shipped my father’s remains to an Orthodox Jewish mortuary in L.A. What was she thinking? My father–defiantly irreligious, militantly rational. He had changed since my mother’s death, but this? When the man from Chevra Kadisha phoned to announce the arrival, I insisted they relinquish the casket at once and deliver it to me.

DAD ALWAYS SAID I WAS TOO CLEVER by half. Being single, I used to irritate my parents by making pronouncements about marriage-that you don’t really understand what marriage means, for example, until you’ve committed adultery. I encouraged them to see it as their rite of passage into being adult, and I repeated this nonsense to justify my own affair with a married man and to encourage Dad to cheat on my mother. He loved her, of course, and so did I, but Mom grew up in a series of foster homes, at least one of them Mormon, and that may be why the wildest thing she ever did, at least in my presence, was drink a cup of tea after making us take note she had dunked the teabag only once. I thought my father deserved more fun.

So did I. In our home, once I reached adolescence, my mother kept the curtains drawn, blinds shut. You couldn’t be too careful with a daughter. She feared I might be standing by the window when the “wrong kind of person” passed by. The house stayed closed-in and gloomy while I was plain and overweight, though I preferred to call myself “chubby” or “pleasantly plump.”

Later, I spent years convincing myself and telling her that fucking was like shaking hands-the polite thing to do when you first meet. “Remarkable,” said my mother, “No guilt, no shame,” in a tone so sour it must have been spiked with envy. I explained that once the sexual tension was broken, everything was smooth and I could focus again on work.

But once upon a time before I equated sex to a handshake, I fell in love with my professor. Intro to Statistics, of all things, hardly English Romantic Poetry. In his arms I could be carried to a place outside myself, outside of time. In bed with the married man I loved, all my longing and waiting and hurt were instantly erased or, at least, assigned to someone else’s past, some unknown person’s life.

Then it was over, twelve years ago, and I took the Big Blue Bus from UCLA to the beach and I walked out on the pier, along the boardwalk, out past the souvenir stalls and the Ferris wheel and the Latinos with fishing rods, up and around to the juggler and the stand-up comic and the magician calling a little girl out of the circle of spectators and over to the barrier at the pier’s edge. I wasn’t going to commit suicide. I was just going to think about it. The water was flat and black and I thought it was strange that a person drowns by swallowing seawater when what you want is to be swallowed by the sea.

Jenna called my name.

I turned and saw her, golden tan, her cut-offs slung so low I could see the little ring in her navel.

She said, “Don’t you remember me?”

I could hear my own breath and my heartbeat and the cries of the gulls, the water lapping against the pilings. When we were in high school, Jenna had died in a car crash.

“It’s me,” she said. The pilings creaked. “Leni.”

How could I not have recognized her? Jenna had been my age but it was her sister Leni who fascinated me. Leni of the exaggerated swaying hips. “That’s what men like,” said my mother, in a tone that made it clear that whatever men liked was not something she wanted me to emulate.

On the pier, not a sound came from my throat until I managed, “Oh.”

Leni reached as if to hug me. What was I supposed to say? I’m so sorry for your loss? How do you bring up death years after the fact to someone with a belly button ring? She asked about me. I noticed her toenails were painted silver. I answered in monosyllables, still trying to figure out what I was supposed to do.

A sexy Filipino-looking guy put an arm around her waist and she bumped her hip against his. “Wanna see if they can get both our names on a grain of sand?”

That’s when I finally spoke–“On a grain of rice”–to correct her.

She went off with him, giggling. I watched them go, hating myself for leaving Jenna’s name unspoken, angry at Leni for being at the beach with a boyfriend when her sister was dead.

That’s when I began to haunt (so to speak) graveyards and funerals. Is that what my father told Olive? Is that all he told her about me? Olive, I wasn’t morbid. I was ashamed at how the fact of death left me silent and so I had to observe how decent people behave. At first I looked down on all the stock phrases and gestures of sympathy, but I learned.

By the time my mother died, I was able to accept condolences with good grace.

BOTH OF MY PARENTS DIED MUCH TOO YOUNG, but of course it’s easier to lose a parent than a child. And the vigils I went to were for children, and I thought of Jenna’s parents and wondered how they were getting on.

We stood outside the precinct house after an unarmed teenage boy was shot dead by police. Even the media has taken to calling this sort of thing “OIS” for Officer Involved Shooting, rather than tragedy or homicide. We chanted the usual words, No justice, No Peace, gathered in front of the school where a six-year-old girl had been caught in gang crossfire. The mother wailed, “I gave birth to her! I gave her life!” In some neighborhoods, this is almost routine, but that doesn’t mean anyone ever gets used to it. People held the mother as she cried, and the flowers and candles, crosses and teddy bears lined the pavement and then grew into a mound, and I thought there had to be more to all this than etiquette and I thought that my body had never given life and I hoped it never would. My father’s first wife, the one he was married to when he met my mother, had no children, which makes it as though she never existed. “I gave her life!” cried the mother and she called for those responsible to come forward. “Please, please, give yourselves up,” and then she said what they all say: “I hope no other mother ever has to go through this.”

I went to work with my mind full of pictures of carnage and grief and I thought how pointless my work was-a statistical analysis of the likely effect legalization of California’s marijuana industry would have on the Mexican cartels. I stared at graphs and curves and numbers and kept thinking about the little girl and what killed her and how once a criminal enterprise exists, it goes on existing. It can always diversify. And I thought that cartels and gangs aren’t created by drugs or the demand for them but by poverty and inequality, humiliation and corruption, and that the solutions are obvious and that no one would implement them while I would continue to draw a salary, watching footnotes overshadow common sense.

Dr. Levitsky called me in. He slapped my report. “This is a political agenda.”

I’m not sure whether he fired me or I quit but I went from doing something meaningless to doing nothing at all.

IF I HAD TO HAVE A ROOMMATE to make the rent, I wanted no drugs, no drama, no vegetarians. In fact, I wanted someone very much like my mother. Kelly is sober and earnest to a fault. Even her cat is exemplary a courteous animal sensitive to my feelings. When I stroke his ginger fur, he licks himself clean to get rid of my scent, but waits until he thinks I’m not looking.

The coffin came, not “disinterred” from the ground but merely removed from storage in a Lisbon crypt. It took four men and a gurney to roll it in.

Kelly turned out to be superstitious. “I’m not sleeping under the same roof as… him.”

MY FATHER’S DEATH WAS SUDDEN, my mother’s slow and the weeks when she was dying may have been the happiest of her life. I don’t think I ever heard my mother laugh-really laugh-until those euphoric days on morphine. I was with her almost all the time and only saw two occasions when her mood changed and then it wasn’t to grief but to anger. The first time was when the hospice worker came and held her hand and asked in gentle tones who she wanted to see, who she wanted to forgive, and was there anyone from whom she needed to ask forgiveness. My mother summoned up her strength to rasp, “Get this person out of here.”

Those days, my mother was greedy for all the pleasure she’d denied herself or been denied. I’d never before seen her so lighthearted or, when she wanted more drug, seen the scheming look in her narrowed eyes.

The morphine kept her happy until the nurse came. “She’s not in pain anymore. Your mother has become an addict.”

I said, “At this point, it hardly matters.”

“Oh, yes it does.”

My mother’s face, pale with impending death, for a moment turned red with rage.

*

RIGHT AFTER DAD RETIRED and before Mom was diagnosed, he booked passage for them on a cruise to the Mexican Riviera. I sometimes thought that was what killed her: she got sick immediately after he announced, “Let’s have some fun!”

My father and I were at her bedside when she died. He threw his arms around me. “My darling!” He sobbed into my shoulder and held me tight as if forgetting for the moment who was who, and I realized that, improbable as it seemed, my parents had loved each other.

My father never thought of giving up his trip. He asked me to cruise to Mexico with him in her stead but the thought of sharing a small state room-well, that was just impossible and would have been even if not for that moment’s desperate embrace. I couldn’t imagine being trapped on one of those floating cities that go out on the ocean pretending it’s as safe as land. So he went alone, though he did not remain that way long.

I stayed home and dreamed about my mother and her death and thought about how she never knew anything about living and had so little of it, neither quality nor quantity, her lifespan so much less than the actuarial table predicts. My father brought back photos. Him with his arm around a former Vegas showgirl, now eighty years old, who was not wearing her bikini top. I thought it charming that he chased elderly tail instead of young flesh. On a Mediterranean cruise he met Olive. She was English and apparently well off and I admit I wondered if my father hooked up with her for her money and I wondered what a wealthy woman could have seen in him. I loved him, of course, but he was a very ordinary, educated, middle-class American, a man who taught a subject he disparaged at a community college.

And Olive-rich and upper-class and British. Maybe she subscribed to stereotype, that Jewish men are good to-and ruled by-their wives.

They first thought to settle in Slovenia and looked at property near Lake Bled, but Olive was put off by the Slavic tourists who paraded around the lake in the skimpiest of swimsuits, obese and unabashed. My father, who’d been content to ogle eighty-year-old breasts, could not have found this so distasteful, but on they went to Sintra, yellow and rose, Romanesque, Moorish, of the winding roads through the mountains and the vistas of the crashing sea; Sintra, or as he put it, they were unmarried and living in Sin-tra-la!, making their home in Portugal because Olive was married to a man permanently confined to a mental hospital and in England (or so she claimed) one cannot divorce a person incapable of comprehending the proceedings .

Unlike my mother, my father didn’t believe in sin. When she was alive, he liked to throw the word around to tease her. After she died, it still had use as irony.

So: Sintra, pink and gold and princely. And Olive, not exactly a double widow-her lunatic husband still living, I believe, though she did marry my father at last after a questionable Portuguese divorce Olive among the “rocky crags” (per the tourist office website) on the Portuguese coast where fishermen are lost at sea and the Portuguese widows wear black and the coastlines begin in grief, only to be transformed sooner or later into resort hotels and real estate for the likes of Olive.

In her e-mail she wrote, “I hired the very best tanatopraxia and

tanatoestetica.” In Portuguese, or at least in Portugal, they have very elaborate words for what they do to a corpse. “The embalming tables are made of marble,” she wrote. “It’s more hygienic.”

The men who carried the coffin into my apartment were probably from Chevra Kadisha but I imagined they were Portuguese too, her henchmen or retainers, those four somber men in their black frock coats and respectable hats who belonged in a painting and not in my foyer, stepping out of the rain looking serious as I thought only Europeans could be.

IN MY COLLEGE DORM, that joyous den of iniquity, someone hung a sign that read Sin Lair. When my mother came to visit, she stood rooted to the spot before it. “Sin,” I said, “the Spanish word for without. Lair, an -ir verb,” though if Mom ever checked the Spanish dictionary, she would not have found it.

And it’s not true that the wildest thing she ever did in my presence was dunk a teabag once. I was very young when one day in Vons she uncharacteristically allowed me to put Sugar Pops in the cart. Then she methodically made her way around the store sticking a straight pin into cartons of milk and orange juice and bags of flour. She was smiling and humming, her eyes glittery the same way they were years later when she said she was in pain. (Oh, no you’re not, said Meryl the nurse; you’re dying, but you’re not in pain.) When the security guard caught her she cried, but she held my hand and I could feel her pulse beating wild and fast and her whole body humming with what I took for fear and now believe was pleasure mixed well with her shame.

My mother had been my father’s student-the waif he wanted to save and instead seduced. Olive nursed him through a bout of food poisoning on board and, once he stopped vomiting, seduced him. How romantic. From her photographs, Olive looks like Ingrid Bergman which means some would find her regal and attractive while I used to stare at Bergman on the screen trying to make sense of her appeal. I found her heavy-boned, with oxlike wrists and ankles, of coarse provenance compared to the birdlike frame of my mother.

Me? I was never a waif I was the stocky, serious girl, studious, fascinated by Jenna’s sister who one day touched my face and said, “Don’t worry. Someday you’ll get yours,” and I thrilled at the promise or the threat that someone would someday want me.

“Oh, she’s not interested in that,” said Jenna.

She was right, I wasn’t interested, but desperate, imprisoned in a teenage body wracked with all the desire that should have brought joy. No one was interested in me, the good girl, till there he was, my professor in front of the classroom, his dark eyes behind glasses, his nervous energy. When he chose me to click through his PowerPoint, he didn’t need to signal. We were perfectly in sync. He spoke of “multiple regression” and “cyclical component” and-I blushed-“goodness of fit.” All it took to get us started was one afternoon, his hand, my pleasantly plump bare arm.

SIN-TRA-LA! WAS MY FATHER BEING IRONIC or singing out the joy that had long been buried deep inside him?

KELLY TAKES ME to ARLINGTON WEST where every Sunday on the sand just north of the pier Veterans for Peace install an anti-war memorial to the American dead in Afghanistan and Iraq. Kelly volunteers every week, but I’ve never gone with her before.

The veterans set up booths and exhibits. Kelly shows me how to use wooden stakes and string to mark off straight rows. I like the logic of it, being so well organized. We start to plant crosses and Stars of David and Islamic crescents in the sand. Kelly says at first there was a marker for each fallen soldier, but soon far too many had died. Now a red cross represents ten, a blue cross a recent death.

I’m about to ask if suicides are included when a skinny white guy makes his way toward us down our row. “Sorry. Hate to disappoint,” he says, “but I am not Jesus Christ.” I stare at the food residue in his beard and he adds, “I am Barack Obama. And I’m not going to produce my birth certificate.”

“Well, that explains everything,” says Kelly as he lopes away. She stabs a Jewish star into the sand and I wonder if this is how she buries disappointment.

We tie the names of the fallen on the crosses and crescents and stars, though we have no idea what religion, if any, goes with each name. Families come and add photographs and messages. Mothers cry.

Year after year fewer volunteers come to the beach, Kelly tells me, till now there aren’t enough to keep the project going. Yet on it goes, just like the wars.

“How long are you going to keep this up?” I ask her. “When do you quit?”

“I won’t,” she says. Then, “Look at him.” There’s a photograph of a young man in uniform, attached with a note-love, always. “He’s so young.”

I point out a photo of a man as old as my father. “Young,” she repeats.

“So are we.”

When I was young- younger- I would think about sacrifice, about giving my life. What would I be willing to die for? For whom? Maybe it’s hormones at that age, the way the life-spirit just zips about your body, not connected firmly enough for you to understand what it would mean to lose it.

“Oh, come on,” she says. “You’re what? Thirty-five?”

“Thirty-two.”

The pier looms above us to the south. Who was the girl who stood there? Who was the man who made statistics so improbably erotic? I can still feel his body on mine, his breath in my ear. I hear his pulse but when I dose my eyes to see him, he’s changed, transparent as a ghost. He never promised me a future, but in bed we erased time. When he erased my past, he also erased any thought of the future and without one there was no death. There was no me. I look to the right, north up the beach, to where the land curves and offers a view of the cliffs and mountains rising from Malibu. Rocky crags.

“Whatever,” says Kelly. “It’s not too late.”

But when I look at her, she’s listening to a woman who stands with her arms full of flowers and I’m not sure Kelly even spoke to me.

The woman walks the rows placing a flower at each grave. One foot in front of the other. Me, I would rather have flowers than any religious marker, though I have to admit flowers are ambiguous. The crosses, stars, and crescents? I can think of no better way to signify death.

The memorial stretches down to the water’s edge, stopping just short of beached seaweed and the tides. The woman with the flowers is crying, though no one is buried here. There are no bodies beneath the sand. And for me to claim my losses match all this carnage, I might as well be one of the people strolling on the pier, looking down on this simulated graveyard, enjoying the sun, falling in love and giggling.

THE COFFIN WAS MADE of heavy and beautiful wood with brass ornamentation. The men carried it in with surreal formality. Dad’s funeral was held in Lisbon where I’ve never been. I know Sintra only from the web. Photographs of the World Heritage Site, the palaces of Monserrate, Castelo da Pena, Queluz, fanciful, roman tic, and so I believe the somber people Olive sent were only showing sympathy for my grief and didn’t suffer from a constitutional lack of joy.

In my apartment they laid the coffin down on the mahogany table I inherited from Mom.

Kelly left, as did the somber men, and I phoned Olive.

“I took care of all the paperwork and the transport,” she said. She waited for me to thank her and I didn’t. “I’ve remarried,” Olive said. “I want my new husband in the mausoleum with me. Your father should be buried with your mother.”

My mother wasn’t buried. My father had her cremated- something a good Jew is not supposed to do. Dad and I took the ferry to Catalina so that he could scatter her ashes en route. Our passage was so smooth, you couldn’t even tell we were on the water. Even so, I got seasick. He got disgusted. My father dropped the urn overboard and it sank in the sea like a stone.

RAIN SHEETS THE WINDOWS. The room is dark and I sit with the cat in my lap, looking at the box that holds my father’s remains.

I’m not surprised when the front door opens and it’s Kelly. I knew she

wouldn’t leave me here alone. She drops her umbrella on the step, puts down a bag. “People are coming,” I say. “They’ll cremate the whole thing.” We both wince at the word thing. I tell her I will throw him overboard to join my mother.

“I’ll go with you,” she says. I’m so sorry for your loss.” She takes out the candles she’s brought and she places them around my father and lights each one, a circle of tiny flames that glow like portholes, and she touches my shoulder-gestures familiar enough to keep me grounded but that do nothing to alleviate my grief.

Somewhere else: the breath of eternity.

Brass gleams with reflected fire. I’m left with the box and with motions to go through, routine enough that even I can get them right.