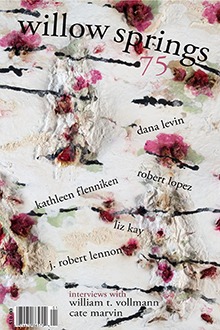

“Melancholia” by Dana Levin

1

Dad and I on a summer motorcycle ride; I’m eleven. It’s incredibly hot, already, as we exit the pancake house. I long to ride without my helmet: how cool it will feel, how I will have to close my eyes against the rush–just then Dad says, “Should we wear our helmets?”

2

It ‘s the kind of movie where a rogue planet named Melancholia is bearing down on the earth, but someone’s getting married–she’s very depressed. At the reception her boss won’t stop hounding her to write better ad copy; her mother insults her while giving a toast. Unsurprisingly, she keeps trying to leave her own wedding: once to fuck a co-worker, once, incredibly, to rake a long bath. People keep trying to change other people’s feelings. They cite “real scientists” and the broadcasted schematics: “They say Melancholia will just pass us by!”

3

Lying in effigy on the couch in the family room, home from work early and not saying a word–after days he’d get up and it’d be a party.

4

The first time I saw a picture of King Henry VIII, I couldn’t believe he had been my dad. Star Trek’s Captain Kirk, actor Brian Keith–one the blowhard Commander rake of space, the other as a diver with a laudanum addiction, sinking in a sea of hallucination as the Krakatoa volcano explodes.

5

Sometimes you meet your secret suicidal death wish with bravado and buy a brand new Datsun 280Z. When your wife goes out of town you promise your nine-year-old daughter you’ll take her to dinner and you do, strapping your bodies into your rocket ship. You’re about to turn left from the cul-de-sac where you live, when a car careens around the corner and nearly hits you. Enraged, you follow it to a driveway, and when it’s parked you get out, demanding the teenage driver pay you some mind.

6

As if I’d known–not thirty minutes later, bike sliding out from us, taking the gravel in the curve. I blacked out for the bulk of it, but for the sudden apparitions, rushing round-mouthed from an old green car–then I was on the bike again and we were gunning the highway: Dad would have to have his broken shoulder set. In the hospital waiting room I hefted my helmet, turning it around, tracing the deep score and the drag–

7

“Yeah,” I say. “We should wear our helmets.”

8

Meanwhile, Melancholia approaches. You stop paying your taxes and soon, without telling her, you stop paying your wife’s. You stockpile Leicas and stereo equipment; you bring home a big telescope we only use twice. You’re about to die soon and you want it all for you. You’re about to die soon because you have just turned fifty and you know you can never outlive your father: fifty-four years old and brained by a tumor. Sometimes it seems like you’ve quit going to work. Sometimes it seems like you’re a traumatized Hansel, stashing candy in bags in a closet. And regarding those taxes: everyone said your father was a saint, but you always knew he was a secret gambler you’ve banked on the moon that blew up in his head.

9

What is a father, what is a star? Fathers blaze glorious at the edge of home planets, they explode above islands and boil the sea. Fathers blast in and flatten the forests: you’re amazed, in the photographs, how many miles of trees.

10

In the dream, the royal family has died. Like all subjects, I’m being ushered into a room where I am to pick liquors from a cabinet: thus we submit to the annihilation of the king and his line. I am careful about what and how much I choose, because I am the father of an ordinary family, and I am deeply unsettled by the death of kings; I want to get out from under the eye of the cabinet functionaries, who stand watchful in their fur-lined cloaks–they flank the cabinet, which is portable and gilded like an altar. I choose two malt 40s for myself, because those are the spirits of the father; mothers receive liquors more delicate. I’m unnerved by the ceremony, by my own

curled-toed shoes–

11

Meanwhile, your daughter’s trapped inside your rocket ship. She’s fixed at the window, watching your rage, so private and familiar, batter a stranger. You ram into the kid and he rams you back, until you topple over–then he jumps on your chest and flails at your face. Finally his own dad comes out and pulls the boy off you. He says, “Go home–” pointing his finger just like you’re a dog. And when you get back in the car, exuberant, bloodied, breathing hard–

12

Fathers get angry if you leave open the screen door or sell weapons to Syria, if you ask for some juice but only drink half. If the sprinklers soak through the morning paper, if there are too many leftovers in the fridge in foil–how then can the fathers target the drones? Use the wrong knife on a prime cut of meat and they’ll set off the end of the world.

13

After the dinner you put on your coats and return to Dad’s rocket ship. He’s going to keep flying as if no one is shipwrecked, he’s going to step on the gas of his disintegrating car–“Let’s drive fast!” you cry and he says, ” What road?” It’s a thrill to accelerate and fly through the night. lt really feels as if you could go up and up, punching through clouds until you hurtle free into the whisk of stars–he slams on the brakes. It’s been raining for days in your birthday desert, and there’s a flood raging across the road. A giant tractor tire bobs by and sinks in the roil. You climb our of the car and stand next to your father, who says, “Look at chat–” enthralled by the surging water–

14

I wake up and decide the dream is stupid. I spend all day not writing it down. “But look,” my sister says, when I later tell her about it. “You chose the spirit of the father.”