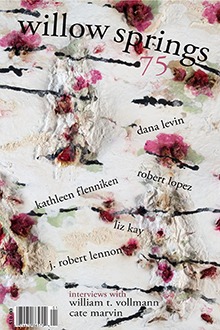

Found in Willow Springs 75

April 12, 2014

DAVID ALASDAIR, MELISSA HUGGINS, GENEVA KAISER

A CONVERSATION WITH WILLIAM T. VOLLMANN

Photo Credit: Elliot Bay Book Company

When I'm dying, I want to think I did what I felt was best for the words I was writing," William T. Vollmann declared in a 2014 essay in the Atlantic. "For an artist... it's good to remember that nothing is true for all time-and therefore, that all is permissible. You shouldn't get stuck in any one truth."

The author of more than twenty books of fiction and nonfiction, Vollmann is known for placing himself in dangerous situations in pursuit of artistic authenticity. That same quality has made him into something of a cult figure among his fans, drawn to the mythology of a writer whom the New York Times Magazine described as showing "a disregard for personal danger that would shame Hunter S. Thompson or Errol Flynn." At twenty-two, he traveled to Afghanistan in hope of supporting the mujahideen rebels' fight against the Soviets; in the early 1990s, he survived a sniper attack in Bosnia that left his companions dead; he also spent two weeks solo at the magnetic North Pole, researching a novel, during which he nearly died of hypothermia. He's written about smoking crack with prostitutes, riding the rails, and visiting a nuclear hot zone in Japan, among other subjects, but says he writes without an intention to shock his readers. "I don't shock myself, and I don't care about shocking others," he told the Paris Review in 1993. "I'm not an egocentric or a performer."

Vollmann has traveled widely in his search for knowledge and understanding, writing about subjects as complex as immigration, poverty, war, climate change, racism, prostitution, and others. He also takes photographs, paints, draws, and produces other artwork in his studio. In 2013, he published a book of photographs, a series of self-portraits, cross-dressing as a woman named Dolores. "Not only am I physically and emotionally attracted to women," he writes in the introduction to the book, "I also wonder what being a woman would be like."

His novel Europe Central won the 2005 National Book Award in fiction, and his seven-volume book on violence, Rising Up and Rising Down, won the 2003 National Book Critics Circle Award. Named by the New Yorker in 1999 as "one of the twenty best writers in America under 40," he has written for many publications, including the New York Times Book Review, Esquire, Spin, Granta, the New Yorker, and Outside Magazine.

In 2012, Harper's published Vollmann's essay, "Life as a Terrorist: Uncovering my FBI File," which recounted Vollmann's discovery, upon filing a request under the Freedom of Information Act, that the FBI once suspected him of being the Unabomber. In the essay, he details the loss of personal freedom he experienced as a result and criticizes what he sees as an American surveillance state.

We spoke with Yollmann during the Get Lit! Festival in Spokane shortly before the publication of his collection Last Stories and Other Stories. We discussed empathy, the importance of story, and his travel to places of conflict.

MELISSA HUGGINS

Empathy is a significant part of both your fiction and nonfiction. In Riding Toward Everywhere, you wrote, "I never want not to feel." Could you elaborate?

WILLIAM T. VOLLMANN

It's discouraging seeing the misery and suffering of others and knowing you can't alleviate most of it. I wonder what kind of a world we are making for ourselves. As far as I can tell, we're doing almost everything wrong. You send money to United Way or another charity and you think about how a lot of it might go toward salaries, and what's left will go toward some policy that may or may not be effective. Does any of it get to the people who need it? I feel similarly about global warming, that there's nothing I can do. A lot of my friends say they put away the paper or turn off the news when they hear about it, because it only upsets them. I don't want to be that way.

I felt reluctant to embark on the book I've been working on about fossil fuels versus nuclear energy, because it's such a dismal and complex subject. But in 2011, I happened to be traveling to Japan right after the tsunami, so I went to Fukushima and visited the forbidden zone. It was extremely upsetting. I returned in 2014 to find that, in many ways, it's worse. There are so many places we would rather not think about-the Hanford nuclear site here in eastern Washington, for example—because the truth is, once there's any sort of radioactive contamination, it will be a problem for centuries. Who wants to face that? The only thing worse than facing it is not facing it. I feel it's my obligation to speak up. Not necessarily to expect I can make a difference, but to try.

HUGGINS

Do you think that's every artist's obligation?

VOLLMANN

No. Nabokov once said that he banished from his bedside any book that told him what he should do or how he should feel. He thought that was almost always bad art.

DAVID ALASDAIR

You've been described as "a globally conscious voice," and you seem to participate in much of what you see. Do you think it's enough to report what you observe, or do you need to be a global participant?

VOLLMANN

Ghandi said that you should consciously eschew the desire for results. Do what you think is right, and hope but not really expect. I think that's a sane and consoling way to look at it, but there's always an opposition between words and action. That was one of the two things that most tortured Yukio Mishima and probably led to his absurd political suicide. He felt like writing great books was not enough. All you can do is your best. You never know how you're going to affect people. I'm proud of the little things I've done for people in different parts of the world, bur for all I know, some of those things have ended up causing harm. You can never be sure. Maybe somebody has read one of my books and decided to do something more important than I ever did. I can hope so, but I'll never know.

ALASDAIR

How is your approach different from that of a journalist?

VOLLMANN

I've met journalists who think the most important thing is getting a good story. I would rather let the good story go if l have to do something indecent. If I have a very clear story, I can be pretty sure I'm missing something, because the answers are always muddled. If someone says, "It's obvious the Taliban are bad," guess what? It's not obvious at all. It doesn't work like that. Things are always more complicated than you think. Of course there's a danger in being paralyzed by that, but maybe that was one of the reasons Nabokov said what he did, how he didn't want the book to declare, "this is this," and "that is that." In a novel, you want things to be ambiguous and nuanced and complicated. Up to a point, that is. You don't want to come away from a book saying, "Well, I don't know whether Hitler was good or evil." But you can say, "It's very interesting that even though he was evil, he was kind to animals, and the people around him liked him." In a way, that makes him worse, more dangerous, more effective. It also means he had the capacity to be good in certain ways, but didn't exercise it. To me, that makes a book more interesting. Of course if you're prosecuting somebody like that at Nuremberg, you say, "It doesn't matter if this Nazi was nice to animals. He deserves the death penalty."

GENEVA KAISER

During your National Book Award acceptance speech, you described how you learned about the Holocaust in school, then learned that you were German. You said you tried to read yourself into that horrible event, to attempt to imagine how anyone could have done that. What do you mean by reading yourself into the event?

VOLLMANN

I think it's something every writer ought to do. Flaubert famously said "Madame Bovary, c'est moi." I have to feel that I'm in all my characters, because the only way for me to make the characters real is to think, If l were this way, then maybe this is what I would have done, and if l believed this, then I would come to this problem that way. Otherwise they're opaque to you. You have to put yourself in everybody you write about. That doesn't mean you have to go out and kill six million Jews to understand Hitler. It simply means asking yourself, What would Hitler think? What would I do if l believed all this garbage? It's a creepy exercise to start imagining yourself being some monster, but a useful one. As long as people are opaque to each other, there's no hope of international or social understanding.

ALASDAIR

When you were younger, did you think you could fix problems you saw in the world?

VOLLMANN

I used to think there were answers. Now I think there are questions. Those questions have to be answered, and once we arrive at an answer we've done something important and necessary, but the most common mistake is to think we've answered a question for all time, that there is no other possible answer. I like what Jung says about the shadow, how there is a dominant paradigm in our consciousness and in society, and that it has come into being for a very good reason and serves its purpose. Whatever we define goodness or justice to be, that is central in our consciousness, while the stuff we define as bad gets pushed to another part of our consciousness, so much so that we feel very strongly about it and can't even consider that there might be something good in it.

Jung also used to say that in a war, the center of evil is usually about a kilometer behind the enemy lines. That's how it is now. People are saying how awful al-Qaeda is, how terrible the drug lords are, how we have to stop the child molesters—and these are all legitimate things to worry about—but as we go on insisting that things are this way and not that way, reality is imperceptibly changing. Suddenly, these concerns are going to be irrelevant. The things that were so important in our parents' time or our grandparents' time—all the worries about the Cold War, how we had to watch out because the Communists were going to come and get us and maybe the Russians were going to start a nuclear war, nowadays, who cares? That's why it's important to always re-examine who we are and what we think we know.

ALASDAIR

Do you think that, as a society, we ask those questions enough? At your reading in Spokane you said, "Each and every one of us here is a potential terrorist," and the audience laughed. Have we come to terms with living in a surveillance society?

VOLLMANN

I think we treat it too seriously. My FBI file is ridiculous, and very possibly so is yours. Without the Freedom of Information Act, I would never know that. Yes, of course, any of us could be a terrorist, and it's almost certain that there will be another September 11, that some terrorist will get through. Maybe there will be a dirty bomb dropped on Spokane someday. Bur part of the problem comes from insisting we know the answer. I'm sure Bush and Obama meant to do good by attacking and continuing to fight in Iraq and Afghanistan, and a lot of people think maybe they have. I don't. I think it's been a disaster. But maybe Bush thought that was all that he could do, that it was the only answer he could see. If I think of it that way, then some of my disgust goes away. But the longer we prosecute these ineffective and unjust wars, the more enemies we make, and the more people are determined to take revenge against us. Even if that weren't so, the fact that people hated us before means they're going to hate us again. Saying that we have to give up so much of what's valuable about being American—being able to say what we want and do what we want, even if it's eccentric or even hateful—for the sake of some illusory safety ... maybe that's like the old military joke: "We had to destroy the town in order to save it."

HUGGINS

Personal freedom is something you examine in many of your essays and books, including Riding Toward Everywhere and Imperial. You seem to be wrestling with a dichotomy of being proud to be American while also experiencing disgust at certain actions or attitudes.

VOLLMANN

I'm very proud of the American Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. The idea of being American is inspiring to me and inspiring to people all over the world, the idea that our homes are our castles, that we can all go to hell in our own way, that we may not be equal in capacity but we are equal before the law, and that we are ruled by a government of laws, not a government of people. But of course all these wonderful things that Whitman expressed so beautifully in Leaves of Grass are mostly illusory. Only a small portion of them have ever been realized. Sure, it was liberty and justice for all, but not for women, not for blacks, not for a long time. Yes, there was a sense of infinite freedom, the ability to go where we wanted on the frontier, but only at the expense of the Natives. I think it's important to remember our history and say that our country is a work in progress. It will never be perfected, because human nature is imperfect, but it's something to strive for. When the Constitution, for instance, is violated, there's no reason to be surprised or shocked. It always has been and always will be. But it's important to say, "I object to this."

I believe, though I cannot prove, that my mail has been opened for many years. Either some yo-yo is opening it, or envelopes aren't what they used to be, the machinery at the postal service is really bad, et cetera. If l get some books from my French publisher, the box is open, and oftentimes the spine of every single book has been carefully slit. I take these nice books and all I can do is throw them in the garbage at the post office. I have no recourse. When that happens year after year, you get a little crabby about it. Is that irritation and sorrow I feel worth saving the rest of you from a dirty bomb in Spokane? Of course it is. But what if it doesn't do anything? As far as I know, I'm pretty harmless, and maybe all of you are harmless, too. So if 99 percent of us are harmless and they started doing this to 99 percent of us, would it be worth it? Of course there's no answer, just a question. I have my answer. But my answer could change if there were a dirty bomb.

KAISER

At the beginning of Poor People, you write that poverty is never political. If it's not political, what do you think it is?

VOLLMANN

Poverty is a state of being. Like everything else it can be politicized, but the people who experience it deserve to own it and to feel it in the way they want to feel it. It's really a facet of consciousness. You could be poor and believe that you were poor for one reason, while I might not think you were poor for that same reason. But you might say, Well, this is how I feel about it. I could be poor and have more money than you. You could have no money and be happy and not consider yourself poor. I think it's important for us not to get in the way of others and say, We're going to define what you are.

HUGGINS

Are there political solutions for poverty?

VOLLMANN

There are political solutions for everything, of course, but people don't agree on politics. They don't agree on what poverty is. There have always been poor people, therefore it's likely that there always will be, therefore there is no permanent solution. To think we can solve it with a stroke of a pen is utopian. In Poor People, I mention that Vlad the Impaler had what he thought was the greatest solution to poverty: he took all the poor people and had a banquet for them and then burned them alive. Problem solved. But guess what? I saw somebody who was poor yesterday, so it wasn't entirely effective.

KAISER

In Poor People, you stated that you pay people for interviews and for taking photographs of them. Do you worry that paying someone for their story will cloud the authenticity of a piece? Is there a risk of someone saying what they think you want to hear or not giving you the full truth?

VOLLMANN

You always have to wonder that, whether you pay people or you don't. You never know for sure, but some of it depends on how you pay and what you're paying for. I think that when people don't have anything, it's the right thing to do. I pay them so I'm not just taking from them. Hopefully, I'll get something out of it, maybe financially, maybe not, but at least I'm going to learn something. It's a lot easier for me to pan with ten, twenty, or a hundred dollars than for them to acquire that amount of money, so why wouldn't I do that?

I know the New York Times has all kinds of guidelines: you can't accept things from the people you're interviewing; you can't let them take you out for dinner; you can't pay for this or that. I can see where they're coming from, but I think that's mistaken. When I interviewed Ted Nugent, he had me over to his house for dinner, and I got to meet his family and see how he cooked some venison that he'd killed. It was great. Of course, I was grateful for the meal, but it didn't change one word I said about him. I like to think we can all be big boys and girls and not sell or buy our opinions for trifles. Upton Sinclair said, "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it." But why not pay people what you can and what seems fair? In a way, I think that's a more freeing thing. If anything, why shouldn't I be able to say what I want to say? They're still getting something out of it, even if I were to say something perceived as negative. It doesn't bind me in any way.

However, it does depend on what you are paying for, what you are asking, how leading your questions are. When I went to Taliban Afghanistan, I expected to dislike the Talibs very much, expected to think that what they were doing was wrong and unpopular, that they were despots. Instead, I mostly found that the Taliban were wildly popular. Since Afghans are devout Muslims, they would tell me, "The Taliban is the most perfect government on Earth. It's so close to the glorious Koran, and we're so lucky to live under the Taliban, because they've protected us from the time when the warlords could just come into your house and carry off your wife or daughter forever, leaving you with no recourse." They said over and over: "Nowadays you can take a gold coin and leave it in the street for twenty-four hours, and it will still be there, because anyone who takes it will get his right hand cut off, thanks to Sharia law. Thank God for the Talibs; they are the greatest."

Of course, I thought, What about the women, what do they think? Again, I found that our perception of the Taliban infringing on the rights of women was not entirely true, because most of the women were rural women, working in the fields, who had never been able to read or write anyway. As I traveled through the fields, they made sure to show me. "Look, here they are with no burqas, you can see their faces, they're working. The only ones who have really suffered are the urban educated women, who are 1 or 2 percent of the population." So I'd say, "Let me talk to a woman and see what she thinks." Which of course was like trying to wander around inside the CIA. To try to talk to a woman? What a disgusting thing to want to do. But sometimes it would be arranged where a woman would lock herself in the bathroom of a house and agree to talk to me through the bathroom door while her husband and son and her brothers were present, all frowning and listening and she'd say, "Oh, yes, I love the Taliban, they're the most perfect government on earth." I'd think, Okay, you have to take that one with a grain of salt. But every now and then, I would manage to meet begging women on the street wearing the burqa, with nobody around, so they could never be identified, and they would tell me the same thing. I would weigh that a little more heavily. They had no particular reason to lie. You can never know for sure, but you can consider when the answer is likely to be skewed. Though I'm sure if I had been a fool and told the man whose wife talked to me from the bathroom that I really wanted her to say the Taliban are terrible, and offered an additional five dollars to get her to say that, I'm sure she would have.

On another trip, I was in Yemen and I knew there was a lot of female circumcision occurring there. I've always been interested in understanding more about it, so I asked my interpreter whether there was anyone I could talk to. I wanted to find out what the families think of it, what the girls think, this and that. He said, "Sure, I'll arrange it. The local butcher is about to cut some girl's parts off tomorrow, and you can come and see." He told me the family would need a couple hundred dollars. I started to suspect that they were going to circumcise their little girl only because I was paying them. So I said, "Oh, no thank you; I guess I don't want to do it." I would have felt awful about something like that. In terms of the difference it would make to that family, a couple hundred dollars would be like $200,000 or $2 million for us.

It's so important to think and think and think before you're in that moment. Usually, you have to make your decision quickly. One of the most important decisions I have to make when I go to a dangerous place is whom to trust when I walk out of the airport. Fortunately, I've never made a wrong decision or I'd be dead. There have been a couple times when I thought, I don't like the way this person is behaving and I'm not gonna do what they're telling me to do. But most of the time you have to look at them, decide right away, and go with it.

When it's only my life, the stakes are relatively low. Hopefully, if something happened to me, I would hardly even know it. But I do want to be careful and think that I'm not victimizing anybody. Most likely, I have. Most likely, we all do without knowing it.

HUGGINS

Would you say that your travels, often to dangerous places of conflict, are driven more by you as a writer or you as a person? Would you have felt compelled to visit those places whether or not you were writing about them?

VOLLMANN

Mostly by myself as a writer. When I first went to Afghanistan, I wanted to do something good. I hoped to write about it later, but the most important thing was to try to do something for the Afghans. When I went back to Taliban Afghanistan twenty years later, I only wanted to write about it. There was nothing fun about going there, and I had no real expectation of being able to accomplish any good, though I still had a feeling of obligation to the people I'd met, who had been so kind to me when I was in my twenties. Sometimes in Sacramento, I hear people say things like, My boyfriend's over in Afghanistan kicking some raghead butt, or something along those lines. That's not the way I look at them, and it's important for me to tell people how great they are. Whether that does any good, I don't know.

ALASDAIR

In An Afghanistan Picture Show, you said, "I always asked for facts and I never thought to ask for stories." Do young writers make the same mistake? Have you changed in that regard?

VOLLMANN

I was an idiot. I think our society tends to make that mistake. We think that if we have some kind of numerical statistic, we really know something. We forget that statistics themselves are only stories. If you look at a beautiful atlas or if you go on the spider web and they simulate something for you onscreen that seems quite real, you have to remember the old maxim of the programmer: garbage in, garbage out. Those things are only as good as their data. A story is like one of the photos I sometimes take with my big 8" x 10" camera. I have a few seconds, I see someone, I say, "Please let me take a picture of you in this doorway," but it could be a year or more until I've printed it and actually look at the photo. That's when I see something about the background or the person's expression and realize, Oh my gosh, this really means that. The camera can see and remember things I can't. It can capture something objective and special about a moment that I wasn't capable of recognizing.

It's the same thing with a story someone tells you. When I interviewed the neo-Nazi skinheads in San Francisco in the 1980s, there was one guy who told me very proudly, "It's so great when we go out and murder the niggers." I thought, Do I have any proof that he ever killed a black guy? In a way, the most important thing is the story itself: that's what he wants to be known for, that's part of his identity. That's in the background of the photograph. That you can trust. When you tell another person something about yourself, you create a persona. You're clothing yourself in something, looking your best. In a way, this was his way of looking his best. The context is so important.

ALASDAIR

For both your fiction and nonfiction, you've traveled to physically experience locations that you're writing about. How important is that to your process?

VOLLMANN

For what I do, I think it's very important. But what I do is not the only way to do anything. In the Seven Dreams books, the subtitle of the series is "A Book of North American Landscapes." The first volume was about the arrival of the Vikings in North America, and I was able to go to Iceland and walk through the ruins of Erik the Red's farm and think, Okay, this is more or less what it looked like to him. These are rocks that he probably gathered with his own hands. Here are the gulls, here's the ocean, here's the midnight sun. How does this make me feel, and how would this constrain me? It's one more way of entering into a person's consciousness. You can't get all the way there, but you can get some of the way. You feel differently in a desert than you do in a forest, so if you're trying to write about forest people, you can enter one and experience a closed-in, teeming feeling, you can think about how there's much less light and how that might make you feel, and how while moving through dark sections of the forest it might be easier to imagine that something sinister and unseen is present. I think that's helpful in trying to recreate the psychology of people.

The immersion is tiring at the beginning, when you haven't brought the material alive. As I was writing Argall I had to build up vocabulary lists of Elizabethan words, and it took a while before it felt natural to use them. As I was writing Fathers and Crows, I had to learn a lot about the different forms of technology used by different Native tribes. You try not to make mistakes. There's a huge amount of drudgery involved. It's like learning a foreign language for me, maybe because I'm not so good at foreign languages. It's tedious trying to memorize vocabulary and syntax. But once you've gotten a little bit of it into your head, you have something to build on and it gets more fun. When I'm near the end of one of these Seven Dreams books, for instance, I almost always dream about the characters at night. I wake up and feel like I'm in that world, and I know exactly what this person or that person would do. Of course, I don't really know what they would have done; I only know what my recreation of them would do. But it's a fun and beautiful feeling. Even if it might be a bleak book, there's something fulfilling about having that kind of play in a world I've dreamed up.

It's wonderful traveling and not knowing what you're going to learn. Tiring, sometimes frightening, but so interesting. You never know how any given day will go. Often you think you haven't accomplished something, and then the last interview, which maybe you'd seen as an afterthought, teaches you so much. But once you're going through the material, you might not know what you've really accomplished and then you find a common thread here and here, although this contradicts that, and you begin to get some kind of a consistent, nuanced picture of the particular subject. That usually happens in the writing. I think it would be a terrible thing to go somewhere and want to write an article about how bad the Taliban is or how good the Taliban is. Because how would I know? In Riding Toward Everywhere, I quoted Thoreau along the lines of, "It's so important not to let our knowledge get in the way of what's far superior, which is our ignorance." As long as I know I'm ignorant when I go somewhere, I have a chance of learning something. Otherwise it's hopeless.

KAISER

Do you put more research into your novels than your nonfiction?

VOLLMANN

In some ways, yes. If you're writing about something that's right in from of you, then of course there's effort involved, but you go out and see what there is to be seen. You don't have to try to imagine what things looked like, so in that sense it's easier. Writing Imperial was kind of a long slog, but I enjoyed it, and so much of it was primarily about what I observed. Even now, I wouldn't say I know enough about illegal aliens to write a novel about them. I would have to do much more research, and it took me a number of nonfiction books dealing with prostitutes before I could create, in my opinion, viable prostitute characters, which I finally started to do in The Royal Family. It takes a while to get to know people.

A while back, I was closing out some of my old notebooks, and found I had some notes that hadn't been used. They were from Sarajevo during the siege, when I took a lot of notes for Rising Up and Rising Down. I don't think I could have written the story "Escape" convincingly without my experiences in Sarajevo. That story is the first in a kind of triptych at the beginning of Last Stories, and in a way, the young couple in the story, who were based on a real couple killed during the siege, gradually turn into ghosts. I decided to protect their posthumous privacy, give myself more freedom, and make up different personalities for the characters so that I could use whatever material I got from people I talked to. It became more vivid than having to look at their photographs and describe them exactly as they were, which would be more the Seven Dreams approach. But the last two times I visited Sarajevo, before I wrote the story, I asked people what they remembered about the siege, and was amazed to find that people told me, "That never really happened. That was just an urban legend." Quite sad, really.

HUGGINS

You've observed that humans, particularly Americans, are terrible at remembering our history. In your example from Bosnia, that couple, who were dubbed the Romeo and Juliet of Sarajevo, did exist. How do you attempt to separate fact from fiction when relying on the stories and memories people relay to you?

VOLLMANN

If you tell people's stories and their own stories change over time, then the fiction is the fact, and that's what you want to report. Often very good things come out of that amnesia. One time, I was writing a story about Cambodian gangs in Stockton, California. Historically there's a lot of unfriendliness between Cambodians and Vietnamese. The two countries have been fighting each other in various forms for many, many centuries. But when these refugees came to Stockton, the kids started getting picked on at school by black and Latino gangs, though they had never known these other ethnic groups. In self-defense, or so they put it, they formed their own gangs. Because all the Asians were lumped together in the eyes of these other groups, Cambodian boys were suddenly going out with Vietnamese or Hmong girls, and they were all the same to each other. Their parents said, "How can you do this, how can you go out with her?" But they'd overcome that. It didn't matter to them anymore. Of course, it's just as much of an unpleasant story as a happy one, since they were joined together in order to fight other ethnic groups. But it's still interesting.

ALASDAIR

Has your view of the world changed over time? Have you become more cynical about people or more optimistic?

VOLLMANN

The longer I live, the more I like individual people, and the more pessimistic I become about groups and institutions and humanity in general. Last fall I gave a lecture in Santa Barbara and there was another speaker, a vegan who advocated for human extinction. Now, I like to eat meat. I have an idealized version of where steak comes from because I used to work on a cattle ranch. I killed the cattle myself, and I thought they had a pretty good life and didn't suffer. But maybe if l saw a factory farm I would think, I really shouldn't do this. Or maybe it would be okay. That's an area in which I've never educated myself.

But I can see where she's coming from. The planet would be better off without us, and it might be that the only thing that would save both us and the planet would be a massive human die-off. Since we don't seem able to regulate our greed, maybe if there were some tremendous epidemic, it would give the ecosystem a chance to recover and save us long term. Would I push that button to kill most of the human race? I don't know; that would be pretty hard.

ALASDAIR

When you see history repeating itself, such as recent events in the Ukraine, do you feel a call to activism, a desire to be part of it?

VOLLMANN

If I were twenty, I would. Now I look at that conflict the same way I look at the situation between Israel and Palestine. It's a very, very old and complicated problem. The only thing I know is that if someone tells me who's right and who's wrong, that is wrong. It would be wonderful to have the privilege of going there to learn what I think, to figure out how I could help someone, but that would take a lot of time and resources. Could I do it? Maybe. But if I do one, probably I don't have enough money or enough years left in my life to do the other. I wish it weren't so. I keep crying to do more for others, wondering whether I have done enough. That's the crazy, haunting thing. It's so easy to harm somebody and so difficult to help anybody. It's really, really hard to know what to do about almost anything.

History repeating itself: that's how it's always been with human beings. Otherwise, children would be better than their parents. But the human race seems to stay at about the same level. You have to expect it.

ALASDAIR

At your reading in Spokane, you spoke about what makes you appreciate Cormac McCarthy's work. Do you think the nihilistic, amoral universe he writes about is close to what you've seen on your travels?

VOLLMANN

I think he's a great writer. Maybe the greatest American writer alive, maybe not. McCarthy is mostly interested in a certain kind of relation between people: in aggression, exploitation, obsession. Sadomasochism. That stuff is all present in humanity, and that's what he chooses to focus his work on. But I don't think the world is so monochromatic. A lot of people are kinder than his characters. Similarly, Shakespeare is a great writer, but I don't believe that people think and act in such complex, colorful ways as he made them think and act. That doesn't make him any less great, it only means he's adhering to a different kind of reality.

One of the reasons I liked McCarthy's Border Trilogy was that I thought it was kind of a departure for him. Suddenly he allowed some human tenderness. The Road is ultimately an optimistic book: it's about the love of a father and his son. All of us who are parents know that in the normal course of things, our job is to prepare our children for our deaths so that they can go on without us. That's exactly what happens in this book. In a way, it's the most normal story in the entire world, which makes it great.

KAISER

It's often been observed that your books are longer than most publishers generally accept. How has your relationship with editors changed over time?

VOLLMANN

It's become easier in the sense that as we all get older, it gets easier to say no. You find out that a consequence of being agreeable is that you get trampled on, and then the book isn't as good. So you might as well say no. Some people think the most important thing is to please their publisher and maximize their sales, and that's fine. They'll say, "My agent thinks I should get rid of this," or, "The bookstore wants me to change the title." A lot of my writer friends do that, and I don't look down on them for it. I only know that if I were going to do something like that, why wouldn't I sell insurance? I could probably make more money.

I would rather do it my way. Then, when I suffer the consequences, as I often do—lower advances and poor sales and so forth—I take responsibility for it, instead of thinking, I did everything I could to please these people, but there was still some unfortunate result; woe is me, what a victim I am. No. I'm proud of the choices I've made, and I would make the same choices again. I was very lucky when I first started publishing to have an editor in Britain. One time I asked her, "How long can the book be?" and she said, "Bill, it has to be as long as it needs to be. No longer and no shorter." That's what I've tried to live by.

That being said, when I write for magazines, I let my stuff be cut all the time, and never once has it been an improvement. I let them do it their way, and they send me the finished version and I throw it in the garbage. They say, "How was it?" and I say, "It was perfect," and they tell me, "Bill, you are so easy to work with." And everyone laughs all the way to the bank.

HUGGINS

Your work often experiments with style. Do you begin with form, or does content determine style?

VOLLMANN

It depends. I originally thought Seven Dreams would all be one volume. But when The Ice Shirt turned into its own book, I realized I wanted to write it in the Norse style, with kennings and so forth, and later I knew Fathers and Crows had to be in that florid, pseudo-French style. If I could, I would do that with each of those novels, make each one appropriate to its period. But a book like Europe Central is told in a more neutral style. The book switches between the Nazi voice and the Soviet voice, and it also has an omniscient narrator telling the story in a certain voice that doesn't necessarily relate to those two warring societies.

Generally speaking, it's more fun for me to write fiction than nonfiction. I had fun in parts of Imperial, but with fiction you can express what you want to say using a beautiful sentence. In nonfiction, it's good if you can make your point with a beautiful, clear sentence, but you can't ever let language get in the way of the important thing you're trying to say. You're less free. The work I call nonfiction is really nonfiction, so I don't make anything up, though there are certainly times when I would like to. In An Afghanistan Picture Show, there's a kind of reverie I had when I was there and I included it, but I would have loved to have made my experiences with the mujahideen a little more dramatic, with a little more finality. But I won't do it. I don't think that's right. However, in nonfiction you are attempting to understand something, and the quest to understand something can be very exciting in its own right.

Fiction, on the other hand, can certainly contain elements of nonfiction, but I'm free to shape those any way I like. In The Dying Grass, the book about Chief Joseph, I deviated from the history more than I often did in Seven Dreams. This was because General Howard divided his army into two columns when they were chasing Joseph, and one column never got to Montana because Joseph took another route, so those people just turned around and disbanded. But because I'd already gotten invested in these characters and I was trying to make their relations with Howard say something important in human terms, I had him keep the whole army together. I don't think there's anything wrong with that, as long as I footnote everything and explain why I didn't have him do this but instead had him do that. Whereas if you're writing something based on a Norse saga, you figure they probably made up a bunch of stuff anyway. You have lots of freedom, just like in the good old days when you could write science fiction about Martians and canals and the watery world of Venus, but those days are long gone.

I change my style all the time. But I don't pay very much attention to what other people tell me to do. There was this neat old guy down in Imperial named Leonard Knight, a Christian guy who started painting a dirt ridge and called it Salvation Mountain. He kept adding more and more paint, and people started donating paint, too. It looks like Candyland down there, except it has all these messages to repent. He must have been at it for more than twenty years, and he died last year. One time he said, "You know, Bill, people are always telling me how to improve, and I know that almost everyone is smarter than I am and I know that if I just did it their way my work would be so much better, but somehow or other, I just keeping doing it my way." He had a big smile on his face. That's how I feel, too. My books are flawed and so are McCarthy's and so are Shakespeare's. Everyone's work is flawed, but at least my flaws are my flaws.