March 2, 2012

Samuel Ligon, Robert Lopez, Joseph Salvatore

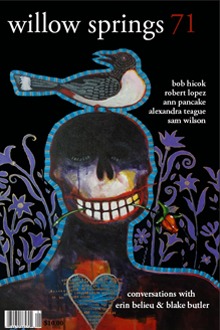

A CONVERSATION WITH BLAKE BUTLER

Photo Credit: believermag.com

In Blake Butler’s work, the ordinary world is made and remade, the familiar becomes strange, the quotidian becomes uncanny, haunted: families discover their own doubles living among them; homes retain their usual dimensions on the outside, but inside are doubling and expanding with secret passages and dark tunnels and strange rooms; caterpillars mysteriously overrun mailboxes and children get inexplicably sick. But that’s mere content. Butler is also a narratologist’s dream dissertation topic. As one of our interviewers, Joseph Salvatore, wrote about There is No Year in The New York Times Book Review: “[T]his novel presents itself as an eye-widening narrative puzzle. Its surface features alone immediately call attention to themselves. Some of the passages are typographically laid down in verse, running Whitmanesque across the page, Dickinsonianly down in thin shafts or randomly in block stanzas. Italics abound. White space abounds. Footnotes are employed, some of them without primary referents: mere subscripts floating on the empty page like gnats.”

Blake Butler was born in Atlanta, Georgia, where he currently lives. He is the author of three novels, Ever, Scorched Atlas, and There is No Year; as well as a nonfiction book, Nothing. Butler also founded and runs the popular website, HTMLGIANT.

A New York Times review of Nothing noted that “Butler is obsessed with the possibilities of syntax, and the most obvious feature of Nothing is a lyric and intellectual buffer overflow that results in long, often interestingly ungrammatical sentences, sometimes stretching over six pages. The most ornate of these is adorned with footnotes, a nod to David Foster Wallace, to whose memory the book is dedicated. As such the book draws attention to its own linguistic surfaces in ways that most memoirs never attempt.” And from the website Creative Loafing: “Nothing is endlessly surprising, funny, exciting, harrowing. There are some cues from the sprawling internal monologues of Nicholson Baker and the genre-defying nonfiction of William T. Vollmann in this expansive exploration of sleeplessness, but Butler is a writer unto himself.”

We met with Mr. Butler at the Palmer House in Chicago, where we talked about ordinary and anti-ordinary worlds, insomnia, dementia, parents and children, the use of footnotes, the internet, popular culture, HTMLGIANT, David Lynch, David Foster Wallace, reading habits, houses and homes, and the problems with metaphor.

ROBERT LOPEZ

All of your books have a post-apocalyptic or dystopic feeling. Can you talk about how the natural world works in your fiction, or how natural and unnatural worlds work together?

BLAKE BUTLER

Those worlds just seem like every day to me, like how going to the grocery store seems hellish. So why shouldn’t I show it in a hellish way? In no way am I the architect. It doesn’t seem like apocalypse; it seems contemporary. That’s what I’m feeling. Maybe it’s more like emotional texture than reality. Maybe I’m angry, without being angry on purpose—like getting up and driving to the room where I’m going to write makes me mad. So, the fact that I have to do it, or whatever other minor orchestration of feelings I have for a day might be what makes me kill people on paper.

SAMUEL LIGON

That room where you go to write is in your former home, your childhood home, and much of your work is about home. How important is that room to your material?

BUTLER

I’m actually afraid of that going away, because I’ve never been able to write anywhere else after getting used to that place. I can do a coffee shop, but it just doesn’t feel right; maybe there’s more emotional texture in that room that comes out in the writing. I write in the dark, with just the computer screen, and for a long time the room was full of crap, like if you turned on the light, it was a room full of trash. But it was all my stuff. It’s the room that used to be my bedroom, and it’s the room I write in now, which is totally weird, right? Nothing was written in that room, and that’s where I edited There Is No Year, but the books before that were written in another room, a second room. I used to write on my mom’s computer. She’s a sewer and an artist and a quilter, and she has a workroom with her computer, and I’d use it to write and if she came in to do anything I’d be like, “You’re ruining my air,” and finally she was like, “Go put your computer in the other room and work in there, and then you won’t be bothered.”

It’s totally weird writing with your parents around, but at this point I do it to save my mom’s brain a little, because she’s dealing with my dad’s dementia, which is pretty deep at this point. He’s basically a toddler: He wears diapers, needs full care at all times, and acts like a child, banging on things all day. He thinks he’s working, so he always wants to be busy, constantly walking around. I get up a lot while I’m writing and go to see him. Someone asked me recently, I think Michael Kimball, “Is the father in There Is No Year your dad?” And I was like, “No man, not at all.” Then I thought more and looked at some of the behavior in the book, and I thought, Yeah, he is.

JOSEPH SALVATORE

There Is No Year seems to include criticism of traditional masculinity, especially regarding fathers and sons. The father in that book is in many ways ineffectual. He’s got weaknesses—his memory is bad, he’s unable to find his way back home, and he watches porn. The mother finds the copy father more pleasant than the “real father.” And the mother is a more active character, with a great deal of agency and depth and heroism, in the Campbellian sense. I don’t hear much about gender issues when I hear Blake Butler being discussed, but they’re at play there with the mother and father. Is that something you think about?

BUTLER

I don’t ever think: The mother’s like this. But when typing, that’s how it comes out. And I’ve always been closer with my mom. She was an art teacher, and read me Don Quixote, Dickens, Twain, all before I could understand any of it. There weren’t children’s books in my house. We read those books. I think I became a big reader because of her.

The way she got me to read when I was little, five or six, she’d buy a bag of books, and she’d let me reach in and take one, without looking. When I finished reading and had talked to her about it for a minute, I could take another one. I don’t think I enjoyed the book as much as I enjoyed the idea of, What else is in that bag? I read voraciously because of that.

And I’ve always been closer with her. I think my dad and I have an interesting relationship, but there was also this distance because he was working constantly. He’d get up at five to go to work and when he was around, it’s not like he wasn’t there, but I just—the one I was surrounded with was my mother. She’s so stellar a person, and creatively, she’s just, like, perfect to me, so I guess that’s where that depth of the mother comes out, just because I see the amount she gives to me and everything around her. I can’t see a mother any way but that. And maybe I like to beat up the dad because I see myself eventually doing things a dad does, and it’s probably more internally me beating myself up than my dad, but some of the agency maybe comes from his actions.

SALVATORE

Does your father have opinions about your writing?

BUTLER

My dad has read one book that I know of—Bill Clinton’s My Life. And he didn’t really read that. He just liked Bill Clinton, so he bought it, but he’s not a reader. He went to a one-room schoolhouse and he never went to college.

LIGON

A mother figure comes up often in your work, but you don’t seem to worry about Freudian implications. Or what the repetition of Mother might mean.

BUTLER

Right. I’d rather look at the thing itself than figure out what’s around it. I’m more interested in images and sounds than I am in plots or unconscious machines behind the thoughts.

LOPEZ

It’s interesting that you say images and sounds. I’ve heard Dawn Raffel—who generally writes short—say that the acoustics of a sentence is basically all she’s concerned about. I think you can get away with that in a short piece, but in longer work, there has to be something more than just sound. Do you consider that in terms of form or the genre you’re working in—that there has to be more than sound? Or is it sound all the way through?

BUTLER

I always thought it was sound, but now I’m thinking it’s more rhythm. I know a lot of people in revision will read their work out loud to see what it sounds like, but I never do. I think I like more the way sentences connect together. I mean, I like interesting sentences, but that’s a given. I’m more interested in how a sentence can reflect an image and then the next sentence comes from that sentence and slightly alters the image. There Is No Year came from one image. The book starts with the mother and father sitting next to each other on the sofa without touching, very close, and that was where the book came from. An image. And I describe the image the way it made sense to describe it, and then started another page, writing scene after scene, and the language was important the whole time and sound was important the whole time and rhythm is what makes me type, because I’m not thinking, you know, just kind of running through what comes to me, analyzing it as I go, you know, as a reader, writing it as a writer and a reader at the same time.

I’m not trying to find anything or reveal anything. I like the feeling of typing and I like the momentum. The times I feel best writing are the times I’m in a frenzy. I get the beginning and then little jumps start happening and you almost completely lose the feeling that you’re typing. And I think that burst is awesome. But you can’t do that for hours and hours. So I’ll leave the desk, letting my mind disconnect from what I was doing. And then I’ll come back and look at where I ended, the feeling of it, and progress from there.

I tried to write books where I stayed and sat in the minute and had an arc that just continued the right way and I was really bad at it. I’d feel like I was under some kind of stress. It wasn’t pleasurable. It was like, How am I going to figure out this problem? I know the guy needs to do this, but how? My solutions were always bad. I couldn’t do the straight line. My line would get so curvy that it was like: This is idiotic; this is a horrible story; you’re not a good storyteller. But I do feel like I know when to respond to images and how to put words to them.

LOPEZ

You alternately use the words “typing” and “writing.” And I’ve seen you refer to “typing” in HTMLGIANT posts. I think about what Capote said regarding Kerouac’s work, something like, “That’s not writing; that’s typing.” Is there a difference in your mind between writing and typing?

BUTLER

I prefer the word “typing,” because it’s not romantic. I don’t like the romantic idea of the writer. I’m repelled by the romance of the ego and the writer. I come from a technical background. I went to Georgia Tech for computer science and I grew up writing code, basic programs, and they told stories on the computer. And that’s typing—you’re typing commands into the computer—and I still think of writing as just that act. I like the more logical, almost proof nature of constructing something. So it’s like I’m not trying to tell a story; I’m almost constructing a proof or a program more than I’m writing. I sometimes think I like writing because all it is is pressing a lot of buttons, and I like pressing buttons.

LOPEZ

So you never write longhand?

BUTLER

I’ve tried and it comes out like I’m an eight-year-old. Just horrible. Or it looks horrible and it feels wrong. It has to be on the machine.

LOPEZ

Your second book, Scorch Atlas, is unlike any other book I’ve seen. Each page is different. Where did that design come from, and how did the visual interact with your text? If that book were to be republished, would how it looks be part of the next incarnation?

BUTLER

The design of the book was all Zach Dodson at Featherproof, an intensely focused designer. I told him I wanted it to look like a beaten up science manual from the 1970s, and he came back with that. The fact that there are like eleven storms raining different stuff from the sky throughout the book, that was all one piece beforehand. It was Zach’s design idea to weave those sections throughout the book, so that he could let each storm affect the look of the pages thereafter, which made the book to me.

My first book, Ever, has brackets throughout. When I sent it to the editor, Derek White, it was all numbered lists and he was like, “The numbers probably work for you to write it, but they look weird on paper.” So he put the brackets in there.

And I got addicted to em dashes. I like visual elements. I think the way you look at something while you’re writing it changes your relationship with it, and that’s why there’s a lot of space play in There Is No Year. Design has always been important to me.

LIGON

When I look at the chapters in Nothing, and the lyrical footnotes, or when I look at the lists you’ve published, I see you playing with form. When are you conscious of the work and the form and shaping it to an end?

BUTLER

I’m a big fan of writing a fast first draft. I like the idea of a book being almost a photograph of your ideas at that time. And because I spent so long trying to write a straight novel—and the longer it took, the more I fucked it up—I try to do a fast draft, because I can get that energy in there. But then returning to it as a reader and revising it, it’s like, Oh, I missed this, or, Look at that thing that’s stuck in here that I didn’t develop at all, and then whole other scenes might eject from that, in the same way that programming is routines and subroutines. It’s very analytical—it can’t be mush; it has to be logically placed ideas that come from not quite knowing what you’re doing.

Those lyrical footnotes try to reconstruct how a thought process works. When I’m trying to go to sleep, the thing that keeps me awake is busy brain. Often, one thought has three thoughts at the same time. So how to mirror that? I can do the run-on sentence and pack a bunch of things into it, but it’s still one thought at a time. And so I looked for moments where it felt like another thought would be inserted, and a lot of times it’s quotes or gibberish, the nature of the other thought so widely varied and particular to a moment. That was my way of trying to replicate multiple thoughts recurring, and they kind of mess you up as you’re reading.

LIGON

I thought the footnotes provided relief in some sentences, acting like punctuation. Sometimes it seemed like a footnote was talking back to the text, while also providing relief, and throughout, the footnotes felt like conscious punctuation. But you’re saying they weren’t?

BUTLER

No. I was trying to punctuate the moment. It wasn’t like I picked any random quote and stuck it there or any random thing. It’s more like this exact thought ejects this exact thought. I could have actually maybe even stuck them in as more of the sentence, but they’re in some way parenthetical and they’re supposed to be happening at the same time. So they’re definitely supposed to continue the logic of the thing. But you can read it without those, too. Still, in order to get that jumbledness of brain, I think it’s important to have them as footnotes.

SALVATORE

The footnotes in your fiction work differently. How would you compare your use of footnotes in There Is No Year to Nothing?

BUTLER

There are only two parts of There Is No Year that have footnotes, the list of people who died young, and the second list mirroring that, and it’s the exact same number of footnotes each time, a mirror image of the sections. That’s why the names look like a spine, because the names were there and now they’re not. I wanted to replicate the list of names, of dead people as being gone, because part of the book is about people being removed from the world before their time. And so that first list is all people who were creators of things, who were then removed and therefore did not create other objects that would have been part of the world. The fact that they’re absent and the objects that they were going to create don’t exist—that’s a residue of sorts. I wanted to show them gone, and at first, the second section was just blank footnotes. But I was like, No, they’re not just blank; there’s something missing where they were going to be, or something left behind, so that’s what the footnotes in the second section do. They’re way more intuitive than abstract, and work in a functional way. The first time the footnotes appear, it’s all, He died in this way; you know, it’s factual and it’s meant to give context to the situation of dying as a human. The second half is the residual.

SALVATORE

And so regarding the missing referents, the footnotes in the second section correspond to the first section of the obituary list—but they seem figuratively connected rather than literally, as in the biographical manner used in the first section. For instance, you have this line, “One white hair grown out on all dogs surrounding.” I read that and had to hunt back through the book and work to understand what that meant. How did you conceptualize that second set of footnotes?

BUTLER

The mirrored section I figured out while I was revising; it wasn’t in the original draft. And when I realized what I wanted to do, I was like, But how am I going to make it work? I was in my mother’s bathtub and I’d go underwater—she has a humongous bathtub—and I figured out that it had to be these pieces like the one you read, and maybe the first one occurred to me as actual words, like I’ll often just think of words and that begins the ejection of other ones. I was lying there and maybe it was the words that came to me or maybe the idea of how it should work. It was probably the words. I got out of the bathtub and went and typed them.

SALVATORE

In a way, the second list functions like a copy family. A mirroring. But in the case of the footnote mirroring David Foster Wallace’s earlier note, when you write the line, “Another Instant for the Night,” should the reader assume that’s the narrator’s comment on Wallace? If so, are we to understand it as poetic? Or something else? Or is it not intended to be read in any way other than merely to experience the language of it?

BUTLER

I don’t know that I did it for each person specifically, but Wallace, he’s last on the list for a reason—because he’s why I started writing. I was at Tech, a computer science major, and I read Infinite Jest and that was the first book that I was like, You can talk like this on paper? You can make these things happen on paper? I became obsessed with him. I think he’s a brain that’s been unmatched. So, to me, he’s one of the biggest examples of that missing thing. He’s a presence still and there’s something not there because he was removed.

LIGON

Do you get irritated when people say they like Wallace’s nonfiction, but not his fiction?

BUTLER

I think it’s idiotic. His nonfiction is amazing, but Infinite Jest is the greatest literary achievement of all time to me. Most people who say that about the nonfiction didn’t read Infinite Jest. And I don’t know if he would think this, but I think it’s clearly his crowning work.

LIGON

When you started writing those widely published numbered lists, it seemed like a move toward nonfiction, because they felt like hybrid poetry/nonfiction pieces. And you’ve now written a book of nonfiction. What’s your relationship to nonfiction versus fiction?

BUTLER

I’ll always write fiction first. Nothing was a specific project. I sold the book before I wrote it and I wrote it to a deadline, the same way I write for the internet for a living. I like the challenge and the puzzle of it, but my heart’s in fiction and I think fiction’s more interesting. That’s you creating space, whereas nonfiction is analyzing space, although you can create space also. But the bigger art to me is fiction. There are a lot of my fictional elements in Nothing that I wanted to get in there, and I’m feeling weird calling it nonfiction, to be honest, because it’s just like a big collage of things to me.

LIGON

But like in the lists, we have these mini-moments in Nothing where you’re bringing the reader specific news from your research. That feels like traditional nonfiction. But then you work against that with other parts of the book, like those lyrical passages.

BUTLER

I don’t know that I’m working against it; that’s just my natural assembly process. I’ve been asked a lot: Do you intend to obfuscate the reader’s direction and challenge them? No, that’s just how I think about things. I started writing the lists because I was working at a collection agency and I came in one day and the guy that was like my overboss, who sat in the desk behind me, I looked at him and I was like, I can’t fucking stand this room right now. The first list came out of me being angry in that room. And then I realized that it was a puzzle, and I challenged myself to write fifty lists of fifty things, and it was like I had a model.

I like the way form can dictate content. I knew certain things about the orchestration of the frame of Nothing when I was beginning it. I’ve been finding that form gives me a structure to play inside of, like it encages you. It’s mathematical more than exploratory.

But as for nonfiction, when I was researching Nothing, I read all these books about insomnia, and they were all so dry and straight ahead. They had an approach, but I wanted to convey the feeling of restlessness and unconscious tension rather than talk about how to solve it. You’re just going to frustrate yourself looking for a cure. Ironically, I entered the best sleeping period of my life after I wrote that book.

SALVATORE

How would you characterize your insomnia? As a clinically diagnosable condition with an objective “cure”? Or is there something more personal and frustrating happening?

BUTLER

I think the latter. I took sleeping pills for a while and they were putting me to sleep, and when I ran out of them I was like, I have to have more of these. What stresses me out usually isn’t the creative thing—like, I have to figure out the next sixteen pages of my novel—or remembering to do something; it’s all entirely garbage thought, and the more you try to stop thinking, the more you think.

I write every day and most of the day, because that’s all I really have to do. The way I work, the way I make money, is partitioned into a different time, but I have most of all day, every day to write. And because of that, I think: I should be writing. I have intense guilt about that. It’s gotten better since I started to accomplish things, but during the time I was having the worst insomnia, I was like, I have to sit down and get something done today so I can feel good enough to sleep tonight. The insomnia would be worse if I didn’t do anything. But that sets you up for a whole lot more shit, because you type and you make this thing and it doesn’t go anywhere and you’re like, Oh, now I feel even worse, because I sat here for eight hours, didn’t make any money, and nothing will come of this except that I spun my wheels some more. But if you’re going to write without the beginning position clear, then you have to do some of that to get to the project that you want to do. And that’s what the list project came from; it was like, I just don’t know how else to get this out of me. I like to have little things between finding the project. It’s almost a puzzle. Like, Oh, I’m going to do this to start the day every day so I at least feel like I did something. I’m completing an equation.

LOPEZ

Your work seems to exist in the moments between wakefulness and sleep. It seems like you couldn’t be who you are unless you were sleepless, and the sleeplessness comes through the work, and almost everything feels born from that and is about that. Would you ever want to be a good sleeper?

BUTLER

Not sleeping knocks you off center a bit. You feel a little crazy. The times I feel most productive are when I am sleeping well, and I’m always fearing sleeplessness, because when you don’t sleep, you can’t get up and write well. It ruins your brain to some extent. But being in that middle zone works pretty well. A good night of sleep for me is five or six hours, so I’m still a little bit off. It takes me like five hours to wake up, before I can really talk to people, so I always feel like I’m in that middle, waking- up-or-going-to-sleep mode.

That’s probably the worst part about sleeping. Because I know I need to be well rested to do what I want to do the next morning, I want to go to sleep. My mania starts around three, and if I’m not feeling tired, it’s like it reverses itself so it’s a self-fulfilling insanity. If I could press a button that said, You will sleep eight hours a night for the rest of your life, I would press it. And I would be the same person. But if I hadn’t gone through that insomnia as a teenager and through my twenties, I’d probably still be coding computers instead of writing.

LOPEZ

Do you think in terms of a body of work, or how your books work together in sequence?

BUTLER

I don’t think about it while I’m writing. I don’t think about anything while I’m writing. I started to think about arc, because I guess I ended up doing more than I thought I would already. But when I sit down, if I think about that, it will make me get on Facebook instead of writing. I have to be blank of mind when I’m typing. It’s good to have an idea of where you’re going, and from the beginning I knew I wanted to write novels and the first thing I ever sat down to write was a novel. I didn’t write poems or short stories—well, I wrote poems when I was sixteen—but after I read Wallace, I was like, I’m going to write a novel now. And I wrote like seven novels that are never going to be anything, because they were all me learning how to write. I learned how to write a novel by writing one and failing over and over, and I finally got to the point where I was broken and wrote the first real one.

I was starting with the story, like, This will be about this. And I’m a bad problem solver in that way. It took me finding out that the less I knew—and actually knowing absolutely nothing and not even thinking—the better. To be able to get to that level of confidence and that level of intuneness with how I type took doing it a lot. And finally, like the fourth of these novels I wrote got me an agent. I published a short piece online and got an agent and he took on this novel. It was called Pupils of an Inflated Giraffe, and it was about two brothers who were in their fifties living with their severely obese mother and it went into all this crazy stuff.

And then I went to an MFA program and they were like, What is this stuff? In the first thing I workshopped, I remember there was some description in there, and the teacher was like, “I can’t see that. I don’t know what that means.” I must have done something weird. But then I was getting beaten up and being encouraged into ways I knew weren’t what I wanted, and writing these novels for this agent, who kept saying, “Oh, it’s weirder, man. You keep getting weirder. Go the other way,” and that’s when small presses were really starting to pick up again, and I thought, I’m just going to send this out myself. Then it worked out its own way and I ended up with a different agent by getting my own book deal. And he probably thinks I’m insane, too. I’m still pretty much selling it myself.

LIGON

Are you interested in plot?

BUTLER

I love plot, but approaching plot as plot doesn’t work for me. I like to fall into plot, write until I figure out what the plot is. The plots create themselves, rather than me creating them. If I think I’m going to write the story of a man who goes home to Wisconsin, the way my brain would want to write that would be horrible. But if I start with a sentence, and the next sentence comes from logic, then that’s still linear storytelling. I feel like I’m telling an A to B story in There Is No Year, even though there are all these weird parts. It has a plot, even if it goes through these weird patterns to get to it.

LIGON

How would you describe the plot of There Is No Year?

BUTLER

There’s a family—a mother, a father, and a son—and the son has been sick with an illness that should have been terminal, but he didn’t die, so he’s kind of living in this phase of death still coming for him, because death didn’t occur like it should have. I would say there are like four plots, though I don’t know how to tell you about all four. It’s the same as the ejection, the thoughts inside of thoughts. There’s a plot about the son not having died and the lure of death and the fact that he’s making this object—he’s writing a book—that should not exist, because he was supposed to die. He’s creating an object that should not exist, and the world doesn’t want him to do that and is trying to destroy him. People living are kind of haunted by this air, like the fact that we live in the middle of all this, and all this has happened over and over again. You know, there’s a kind of air that we live in. . . I don’t even know what it is. This is the problem of me trying to tell a story. I see so many plots working at the same time.

After I gave this to my editor, he said, “So I’ve read the book eleven times, and I think I know what it’s about now—I think the father is molesting the son.” And I was like, “That is not what this is about at all.” Then he showed me all this weird penile imagery. He pointed out these things and I was like, I’ll have to get rid of that. I added 10,000 words and then removed 5,000, because I was like, I don’t want this to go that direction, and I do want it to go this direction, and, Look here’s this thing I didn’t find, like another room I should add.

SALVATORE

If you were teaching young writers, how would you help them understand the notion of plot? I guess to do that you’d have to define it. How would you do that?

BUTLER

Plot is what happens to the reader while they’re reading the book. It’s more effect based to me than a story. Traditionally, plot is the story that happens, but I want it to be more interactive than that, and that’s why I use images that could mean multiple things. People often have different responses to a book, and I like the fact that it’s open-ended enough within the logical plot that it can go these multiple directions. The reader has to be involved with that. Even though the object is the object and what’s in the book is in the book, the person interfacing with it, their approach, is going to change the field, right? I like the fact that I have a vision of what I feel the book does that no one’s ever said exactly, and I like that people say different things.

SALVATORE

Regarding that idea of plot being the reader’s journey, when I get to a section from There Is No Year like, “Passing the parents’ bedroom he heard the mother talking to herself in a language the son had only heard one time,” I wonder, When was that “one time”? In a traditionally plotted book, that might be a moment where you get a flashback to a specific “one time.” The passage continues after a dash, “heard through the crack of his old bed frame, the bed the men in plastic had come to haul away—the bed the doctors said had been infested and was the reason he got sick. The son knew that wasn’t why he had gotten sick. It was a bed. No one would listen. The son had heard the mother’s language noises once coming also from a crack in his newer bed, but he stuffed the crack with gum. The house would sing to him for hours. The son did not try the parents’ door.”

But the source of the son’s illness really isn’t the point, and whether the doctors got the diagnosis right isn’t the point, and this “one time” when he’d heard the mother’s talk is not really a plot point at all. So, for me, there were strands that I felt never got tied up. You said earlier that the one time you tried to write a “straight novel”—and it’s interesting that Lynch has a movie called The Straight Story—you said you “fucked it all up.” So when you talk about extracting 5,000 words and putting in 10,000, are you worrying about connecting dots, or are you going to put this object or that image out there and let the reader do what she will with it?

BUTLER

It’s more like setting up the frame for it to go in. I don’t want to explain away the image, but the image has an order, right? So I’m looking for moments where image is giving too much or giving too little and I’m trying to organize it in a way where it opens more, instead of closes. The reason I love David Lynch and the reason I love reading is that they open things I didn’t understand before. Or they bring me things I couldn’t experience anywhere else that make my brain come alive.

The image of the white horse from Twin Peaks is a haunting image, and the man behind the dumpster in Mulholland Drive is terrifying. Why? Because Lynch doesn’t say, “The horse is this. Or that.” He has no idea. That’s not to say that the image of the horse should not be specific. You have to fine tune all the elements of the image, even if you don’t know what the image is doing. And I also like to pile things in. For instance, there’s a reference to every Lynch film in There Is No Year. I like using other people’s containers in ways that, like, I steal the idea, but not in a palpable way, more a way of figuring out how to say what I wanted to say.

SALVATORE

The egg in the novel reminded me of the black box in Lynch’s Mulholland Drive.

BUTLER

And there’s one point where the father’s walking through the house and I write, “The father aged eighteen months,” or something like that, and that comes from Eraserhead. When they were filming Eraserhead, it took so long to get enough money to film it, you see Jack Nance walk up to the door, and he opens the door and comes in and, literally, in the change of the shot, there were eighteen months between, and he looks exactly the same. I love the discontinuity within the continuity. Or I remember reading William Vollman talking about how he revises. He talked about messing with a sentence, packing things into it and removing things till it pops like a popcorn kernel. It was this egg-shaped thing and all of a sudden it explodes into all these textures. I love reading and thinking about sentences in that way.

LIGON

You often use repetition, even certain words coming up over and over, like “meat,” “air,” “light.” How does repetition serve your work?

BUTLER

I feel comforted by repetition. I try to live every day as if it were the same day. In my ultimate world, every day would be the same day, in which nothing happens except I sit in a room and do what I want by myself. The art I like does that too. And so I keep saying “hair” and “light” because I can’t stop. If I’m writing without thinking about it, those are the words that are going to keep coming out of my hands. I do it too close in sentences, or it feels redundant, I like that it can create a texture—but you can overtexture something. I’ll try not to use the same words in the same sentences unless I mean to. You know, like I’ll go back and be like, Oh, I said this twice and it’s just kind of annoying. It doesn’t have that ecstatic repetition; it’s an annoying repetition.

LIGON

You seem to trust image and metaphor and let metaphor do a lot of work. But in a footnote in Nothing, you wrote, “There’s no such thing as metaphor.”

BUTLER

I have a good buddy and we get in this metaphor argument all the time. Metaphor seems like an orchestration to me. When I say that there’s a closet full of hair, I want there to be a closet of hair. When I say the father aged eighteen months walking across the living room, I want that to happen. The same goes with the copy family. And that’s real; that’s not science fiction. Like you have copies of yourself. I think it’s so defeatist to call that a metaphor, because that compacts the world in a way that’s boring. The art I like makes me know that those things exist, even if it’s like believing in god. I believe in the fact that there can be seven of me in a room that I can’t see. Or that anything can happen.

When you say something in fiction happens, you’re creating that instance, and that’s why fiction’s not just reciting your mom’s bedtime stories. It’s creating space, rather than explaining it. That’s why I love Lynch. Because the rooms in Lynch are places, and they don’t have a name, but they’re places, and you can think about those places and you can traverse those places and they didn’t exist before he orchestrated them, and that’s why the deletion of people making those spaces is so important to There Is No Year.

And that’s why the reader is part of plot to me, because I can’t control what that is. Because you’re going to read “hair” and without even thinking about it, hair is going to mean one thing to you and it’s going to mean another thing to someone else.

Maybe my problem with metaphor is that I don’t want there to be one specific thing that it stands for. It should be all the things that it could be. That’s why you don’t pick one or explain it, and that’s why movies that do explain or books that explain, I don’t think about them after that—Okay, that’s what you were trying to tell me, I got it. I heard that. But I want to be haunted by a book. I want to be haunted by an object. That’s art. I like to read things that wash over me. I like to not have to organize myself when I’m reading. I want to be pushed and knocked around and then think, Oh, what just happened? I don’t know, but I felt something was happening.

SALVATORE

When I first met the copy family in There Is No Year, I thought they were a metaphor for the dark side of a family, but it never turns out to be anything like that. And so I believe you when you say you’re not thinking about metaphor when you write.

BUTLER

I’m saying it’s obsequious or overbearing, because so many people do rely on metaphor, and I think it’s important to counteract it by saying metaphor doesn’t exist. Of course metaphor does things. That’s just an abstract way of saying there are bigger things than the thing is, and that’s fine. But I’m going to shit on the feeling of the traditional use of metaphor, because I think it’s destructive to the language and books.

LIGON

Poets talk about how a poem teaches you how to read it, that you learn how to read the poem by being in the poem—and I think your work operates that way. There was a moment when I was reading Nothing that I realized what I was doing was experiencing consciousness, and needed to let that wash over me.

SALVATORE

And in There Is No Year, I had to admit that I wasn’t fully going to understand everything, but I felt the author was in some kind of control. And so I give up trying to read it as a “conventional” novel, as though certain details were clues: like, Oh, I get it: The son got sick because he was incested or because the mother drank when she was pregnant with him—the family-secret plot. I came around to accept that that’s not the way this book was going to work.

BUTLER

I hope to be in control of the thing. I don’t want it to be a mess, and I get frustrated when a reader comes to a book with expectations, and if those expectations aren’t met, then the art failed, or they just give it up. To me, the fun of reading is going into the book—books shouldn’t be entertainment, or at least the books I’m interested in.

SALVATORE

David Foster Wallace would say that it’s got to be fun.

BUTLER

I’m not saying it shouldn’t be fun. I’m saying a reader should come with a willingness to be open to this game. A lot of people read and they’re like, I want this out of this book, and what I got didn’t make sense to me. And I think, You didn’t even try. Just keep going. Why not experience something without knowing what it is? So entertain, sure. But create a space rather than explain a space. I don’t want to read a book that’s all work for me. And I think there are a lot of funny parts in my work that are dark because of the dark context, but it’s supposed to be a fun thing, though not to provide a solution on a platter. Brian Evenson was important to me in learning how to tell a fun and compelling story, but also to be doing something inexplicable, while incorporating horror tropes and terror tropes—doing the same thing a horror movie does, but also opening into an intense space. And that’s entertainment to me. I have fun reading that. But it should keep you wanting to do it. Books fail that try to do these grand things and don’t get that the reader needs to pay attention.

SALVATORE

Are there any works you’ve come to with certain expectations as a reader, and then found yourself resistant?

BUTLER

Often the way it happens is that the book explains too much to me. I don’t need you to tell me this. It’s disrespectful. It’s like assuming the reader can’t do some work. I’m looking for a reader who’s interested and wants to be in that puzzle. I can’t force someone to work a puzzle.

LIGON

How has the internet shaped you as an artist?

BUTLER

I can’t write without it. If the computer is not attached to the internet, I’m not going to write. Because that comes into play under my anxiety. While I’m writing, my Gmail, Twitter, and probably two other things are open, and I am constantly going back and forth between what I’m writing and links and things. So I’ll write in a burst, and like I said, I get up, or I read a website for a minute. I think that gives your brain a turn off moment where you stop over-analyzing what you just did, and that gives you a reset and feeds you in ways that you don’t realize you’re getting fed. You read a story and it gives you something, changes your mood, and that gives a palette for your writing to change into, unprompted. I like being chaotically programmed by my emotions, and maybe that’s sadistic. To me, typing without the internet on my computer feels like writing longhand. I need that machine.

But I hope I’m not part of that machine. It’s a sick space, but I mean, I sleep with the computer on my bed at this point. It’s the first thing I do in the morning, the last thing I do at night. I spend more time with it than anything. But I’m looking at the same seven websites, refreshing them, e-mailing people, Gmail chatting.

LIGON

How much of your day is taken up with HTMLGIANT?

BUTLER

Usually not very much. I don’t really edit anything. Everyone writes whatever they want. I correct the way it looks. I orchestrate the tastes and pick the people that are in there. I tune in enough to pay attention to the feel of the website. I’m more interested in being a facilitator and putting my own voice in, but not controlling it.

There’s pretty decent traffic and I think that’s because there’s not a critical apparatus for the kind of writing I’m interested in. There are a lot of people putting it out there, but there aren’t a lot of places for it to be discussed and analyzed. So I want a forum. I want a conversation. I don’t have people that I really talk with about writing much at home, and the only way I’m not just a sad bastard in a room typing on my mom’s computer is that there are other people inside this box. I built a place to play with those people.

And it’s a place to get rid of some of the tension that comes from sitting on the internet all day, a place to talk about books. It’s like a mess and intellectual at the same time. Hopefully, it brings people together. The reason we started it is that I was reading thirty different blogs on my RSS feed, all these websites, and I was like, Why don’t we just put these people in the same place, instead of these people just barking in their own area. And why do I have to go to this website and refresh to see if this new thing is up. Why isn’t there a site that will just tell me? I think we meant at the beginning to have more of a “new issue of x or y” and blah blah blah, and we did that for a while, but it’s become more of a conversation now, and a place to have conversations.

SALVATORE

In There Is No Year there’s a string of stuff about celebrities, most of whom are dead. Those sections were the places I felt the author’s controlling hand most, setting up quotes to frame certain sections. What role does popular culture play in your work?

BUTLER

A question I’ve gotten a few times is: Why are the characters nameless, but then, McDonald’s has a name. And I think, Because I thought it was funny. That was where it came from, but I also like the idea of absorbing auras from things. I can mention Sharon Tate and quote her and that automatically sets this weird tone. It’s like stealing the tone. In There Is No Year, the object that the son’s trying to make, that shouldn’t exist, is a book that transcends possible, transcends what a book can do. It contains all things. I like the idea that all objects could contain all other objects. That doesn’t answer why I would use McDonald’s. I think it comes down to the comedic, mixed with eeriness. The child is nameless, but the buildings around him aren’t. That, to me, seems like a kind of deleting in a way, and it makes the body of the person a specific site, whereas McDonald’s is a site that exists all over the world, but with one floor of sorts. Or how Walmart seems to have this weird air, and you think about it as Walmart, but the feeling of being in a Walmart is very specific. And it’s as compelling in its own way as a desert.