April 21, 2006

Jeffrey Dodd and Jessica Moll

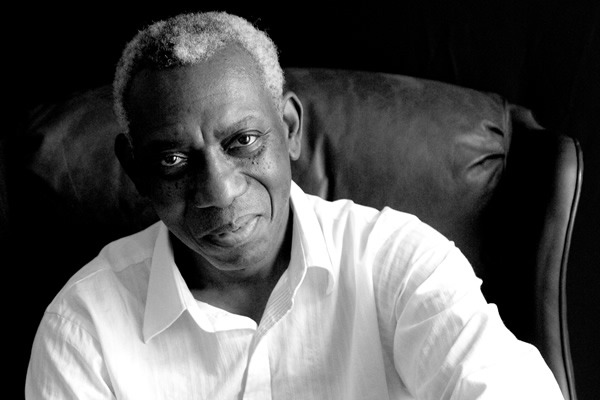

A CONVERSATION WITH YUSEF KOMUNYAKAA

Photo Credit: dodgepoetry.org

CONTRIBUTING TO A ROUND TABLE DISCUSSION celebrating The American Poetry Review’s 25th anniversary, Yusef Komunyakaa described a vision of American poetry: “Ezra Pound beside Amiri Baraka and H.D. flanking Toi Derricotte, Joy Harjo back-to-back with Frank O’Hara and Garrett Hongo alongside William Carlos Williams or Wallace Stevens—a continuum of impulses and possibilities that creates a map…” While modesty might prevent Komunyakaa from placing himself in this vision, abreast Mina Loy, say, or Theodore Roethke, the fact remains that his is one of the most intriguing voices in contemporary American letters.

The “impulses and possibilities” of Komunyakaa’s poetry depend upon precise imagery that points toward an essential experience, while reminding us that this experience must be grounded in external context. In his recent poem “Tree Ghost,” the speaker moves swiftly from a discovery of “three untouched mice dead / along the afternoon footpath” to an embrace of connection: “I can almost feel / how the owl’s beauty scared the mice / to death, how the shadow of her wings / was a god passing over the grass.” How many gods shadow us daily, scaring us nearly to death with their beauty?

The provocation of such questions is a major strength of Komunyakaa’s work, achieved through mastery of image, rhythm, and diction marshaled on behalf of a conviction that “poetry in our complex society connects us to lyrical tension that has everything to do with discovery and the act of becoming.” Poetry is not mere experimentation. That view, he says, “is a kind of selling out—to remain in that landscape of the abstract, when there’s so much happening around us. Not that the politics of observation should be on the surface of the poem. But we want human voices that are believable.”

Komunyakaa has achieved this humanity in more than a dozen collections of poetry, of which Taboo: The Wishbone Trilogy, Part 1 is the most recent. He has been honored as a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, and has won the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award and the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. He recently joined the faculty at New York University, taking the position vacated by Galway Kinnell. After giving a public reading for Get Lit!, the annual literary festival sponsored by Eastern Washington University Press, Komunyakaa met with us at the Palm Court Grill in Spokane.

JESSICA MOLL

The slightly elongated lines in a poem you read from last night, “Requiem,” allow for a flooding sensation that you can hear when the poem is read aloud. What might tip you off to a formal necessity?

YUSEF KOMUNYAKAA

For “Requiem,” I think the subject matter dictated the poem’s structure. I had been asked to consider writing a poem about Hurricane Katrina, and after thinking about it for a while, I said yes to the editor of Oxford American. I said to myself, Well, I’ll write the first part for the magazine and then continue, because now I see this as a book-length poem. I knew I wanted “Requiem” to have long and short lines. I wanted movement on the page, because that happens with water, that happens with chaos. And also I remembered Richard Hugo saying that the poem needs a combination of long and short lines. Years ago when I was wrestling with this concept, it took me some time to understand what Hugo meant. But he’d also mentioned that he loved swing music, that he was influenced by swing. Long and short lines—swing music—it now made sense to me. He was talking about a kind of modulation that takes place, a movement that happens in music and language. I knew that “Requiem” was a long poem, its changes and ebbs held together by ellipses. So it’s one sentence, basically, with a one-word refrain. And that one word is “already.”

JEFFREY DODD

Does the role of the refrain in your work—in a poem like “The Same Beat,” for example—find its roots in the musical tradition and diction and speech patterns of where you grew up, or in a broader Western poetic tradition?

KOMUNYAKAA

I think it is associated with storytelling. How I began hearing stories. Having grown up in rural Louisiana, I remember people telling lengthy stories, and such verbal escapades were mainly paced through repetition. One can view the refrain as a call seeking a response. But also, I use the refrain, sometimes, as part of the process in composing the poem. And then I may extract the refrain from the poem. So, in this sense, one could say that the finished poem has been driven by a false engine. Unless a refrain functions as an integral part of a poem, as an element of its natural pace and breath, it can be viewed as merely a formal gesture, as an unnecessary stroke on the emotional canvas. Of course, I’m also thinking of music. After being asked to consider reading on HBO’s Def Poetry Jam, I wrote “The Same Beat,” and it began with this: “I don’t want the same beat.” There’s an insistence tangled in this voice, and I think it gave me permission to pursue the poem.

MOLL

So the refrain was just a way to get you into the subject matter of the poem?

KOMUNYAKAA

Yes. And, in that sense, that’s what I mean by a false engine. However, it doesn’t falsify. It helps us to get to a basic truth.

MOLL

I suppose there are refrains in visual art, too.

KOMUNYAKAA

That’s right. Colors don’t remain static on the canvas. There’s movement. The images and the hues force the eye into the rhythm of reason. Colors create a dialogue. It depends on how we’re willing to dance with a painting. How many places we’re willing to stand and view it. I love visual art. Often I daydream about it, not necessarily about putting paint on canvas, but maybe about creating sculpture.

DODD

In earlier interviews, you’ve mentioned Romare Bearden and Giacometti and a whole list of artists who push against representational images. How does that anti-representational move work in your poetry, when your images seem uniquely representational—so striking, so precise. Is there a complementary understanding between your view of visual art and written images?

KOMUNYAKAA

I think where the abstraction exists is actually in that space between images. And that space helps to create tension in a work of art. In writing or music this space often equals silence. I suppose, what we’re really talking about here is a way of thinking and seeing, a way of dreaming and embracing possibility. For instance, in thinking about Picasso, it is important to note that he started out as a representational artist.

Probably because his father was a representational artist, who stopped painting after seeing early paintings by his son. Then, of course, as we know, Picasso’s work takes on an abstracted dimension clearly influenced by West African sculpture. It’s what we now call cubism. There’s that story about Picasso and Apollinaire stealing a few small African statues from the Louvre. Supposedly, Apollinaire was arrested, but he refused to incriminate Picasso. The poet takes all the blame. That says something about Picasso, I suppose.

MOLL

I’m curious about your interest in Bearden—does the idea of finding things in the world and placing them side by side to create art come into play in your writing?

KOMUNYAKAA

Bearden studied mathematics when he attended NYU. When he uses collage technique, it seems mathematical. So many beginning painters have attempted imitating Bearden, and it doesn’t work. But if you look at his more impressionistic paintings, especially the ones painted in France—if you look at those paintings beside his collages, they’re very different. And yet, they possess an aspect of the collage, and I think that has something to do with movement. How colors are juxtaposed against each other. He’s one of my favorite American painters. Along with many others, such as Norman Lewis, an African American painting around the time of Jackson Pollock. He’s rather political as well. There’s a photograph of him with some other artists, protesting the lack of work by black artists exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. To get back to the heart of your question, I have to say this: I like how ideas and images fit into a single frame of reference to create tension, how things can be taken from the natural world and placed in the world of the imagination.

MOLL

Listening to you read “The Same Beat” last night, some of the lines that stood out referred to people in the music industry “selling out.” There was the line about a guy with a mouth full of gold—

KOMUNYAKAA

The one already bought and sold.

MOLL

Do writers confront that phenomenon at all?

KOMUNYAKAA

Writers do confront that phenomenon. I’ve written about the erasure that takes place in some contemporary poetry through over-experimentation. That’s a kind of selling out—to remain in that landscape of the abstract, when there’s so much happening to us and around us. Not that the politics of observation should be on the surface of the poem. But we want human voices that are believable, and that’s why Walt Whitman is so interesting to me. Whitman addresses everything, and is clearly influenced by Italian opera, so everything reaches for a crescendo—but he didn’t dodge anything. He really confronts the essence of being an American. Even though there’s fetishism, or, I should say, there are certain characters on his poetic canvas that become eroticized. I do think that contemporary poetry confronts a lot. If you think about the importance of someone like Ginsberg, and “Howl”—if “Howl” hadn’t appeared, in 1958, I hate to think where American poetry would now be. There were some brave souls to come along and confront the Fugitives.

DODD

Ransom and Tate?

KOMUNYAKAA

Ransom and Tate. Was it Tate, who, at Vanderbilt, campaigned against Langston Hughes and his poetry? I think so. Look, we have come so far, in a way, within the last thirty or forty years. There’s Tate pleading to academia, “Don’t recognize Hughes.”

These were the Agrarians, the Southern Agrarians, but this wasn’t the only camp of poetic expression that was stuck in the mud in America.

DODD

Do you think the Fugitives got “stuck in the mud” because they confused politics for art, or confused the function of politics in art? It seems they made so many statements trying to maintain their southern regionalism in the midst of the Depression, trying to make these economic arguments for which they weren’t trained at all.

KOMUNYAKAA

And also, they weren’t farmers either. They were removed from the realities of farm life. But they were presenting themselves as the voice of the agrarians, though they didn’t understand the machinery of economics. They did, however, understand the politics of culture and race in America, as well as the divide and conquer stratagem. The Fugitives had to know that language is political.

DODD

They seemed to underestimate the power of capitalism, even during the Depression, when nobody had anything. They seemed to misunderstand how powerful the popular response to capitalism would be.

KOMUNYAKAA

They didn’t want to deal with a critique of the social realities of the time. And Hughes’s work attempted to criticize the hierarchies of power. The Agrarians didn’t want to face themselves in the mirror, basically, because they were a part of the structure that had systematically benefited from privilege. So it’s interesting that we would have poets who refused to give voice to an individual because of the color of his skin, and also because of his politics, his audacity to confront the beast that hurled hardship onto the backs of his brothers and sisters.

DODD

It seems that Robert Penn Warren was the only one who even made an effort to re-evaluate his position in that social reality, moving into the 1950s and 1960s.

KOMUNYAKAA

Robert Penn Warren was different. I was probably nineteen or twenty when I first read Promises. Penn Warren seems to have had an ongoing dialogue with Ralph Ellison, and I don’t know if the bulk of that has been published or recorded.

DODD

There were a couple of interviews, one in which Ellison interviewed Warren for The Paris Review, and one in which Warren interviewed Ellison for Warren’s 1965 book, Who Speaks for the Negro? But they’re ambivalent interactions, as though Ellison doesn’t quite trust that

Warren isn’t simply an unreconstructed southerner, a suspicion that he’s making these efforts to rehabilitate his reputation. And it seems as though there’s no way to prove the sincerity of his re-evaluation of his early views. He spent his whole life writing against his segregationist essay, “The Briar Patch.”

KOMUNYAKAA

How did he even enter that dialogue—because he’s younger than Tate and Ransom. And, of course, after being beckoned to the Fugitives, he tried to distance himself from that movement and its agenda. But he’d already been implicated. He couldn’t outrun “Here we take our stand,” that line from “Dixie.” I would’ve loved overhearing those discussions between Warren and Ellison.

DODD

Last night you talked about how you see silence as part of the emotional music of Samuel Beckett’s work. Does the silence in music and drama work the same way in poetry?

KOMUNYAKAA

Maybe it works slightly differently in poetry, because the silence begs for an abbreviated meditation to take place. And I don’t know if that happens, especially, in music. It definitely occurs in drama, where silence is an intricate part of the narrative. In that sense, silence is dramatic. In poetry, since the reader is sitting there with the page, and even in a reading by the poet it can take place—a silence—because of stanza breaks. So, I view silence in the poem as a moment of meditation. I think someone said that there should be space enough to fit one’s heart into. That resonates with me.

DODD

Enough space for the reader to become fully invested in the action on the page?

KOMUNYAKAA

Poetry is an action. It relies on the image, on the music in each line. Perhaps that’s why the reader usually refuses to embrace statement in poetry as readily as in prose. There’s an active investment, and that’s why a poem can have multiple meanings. The meaning is shaped by what an individual brings to the poem. A poem isn’t an ad for an emotion.

MOLL

When you’re composing, and you decide how to put the words on the page visually, do you hear the silence as much as you hear the music of the words?

KOMUNYAKAA

I hear the silence because I read everything aloud as I compose the poem. The ear is a great editor. I hear the silence in the music of language. Not exaggerated, but as a part of the natural continuity of process.

DODD

Who was the first poet you learned that from, to hear the music as well as the silence?

KOMUNYAKAA

I suppose when I first began to think about it, I was reading Emily Dickinson. There’s so much silence in her work. But I don’t believe it is a silence that erases content. In fact, in her poetry, it seems to inform content. I was interested in what wasn’t being said as much as in what was being said. Her poetry always makes my mind very active, as if I’m attempting to seek a dialogue with the unknown or the unknowable. This is entirely different from Whitman, although as a poet I embrace Whitman more, with his long lines. And again, the length of the lines, the long lines, seems to beg meditation as opposed to the vertical trajectory of short lines. For the most part, I embrace the short line, and maybe that has something to do with contemporary time, the way everything seems sped up. There’s a kind of vertical plunge of the poem.

MOLL

How does writing plays, with its importance on setting up a dramatic scene and moving the narrative forward, inform your poetry? Are you learning new things from working in another genre?

KOMUNYAKAA

Not really. I think maybe I’m bringing something from poetry over to drama. I realized that poetry could be an ally in my first play, Gilgamesh, which is an adaptation I wrote for the stage. It is primarily a verse play, with limited moments of silence. Of course, it would depend on the director, whether he or she wishes to introduce certain silences. In the play I’m working on now, called The Deacons, there are numerous places for silence—matter of fact, I express it there in the notes: “Pause” or “Silence.” Each piece, whether poem or play, is propelled by its own language and music because the speakers are different in their unique physical and emotional landscapes.

DODD

How does the process of collaboration enliven a project, open new doors, or ask you to look at your work in new ways?

KOMUNYAKAA

I welcome the perspective, the energy. In that way, it’s almost like an ensemble. We begin, and from the outset, we are trying to visualize where the process is going to take us. But it’s always most interesting to see what happens in between, in that space where surprises occur. I trust my collaborators. Otherwise I wouldn’t do it. I’m hoping that these kinds of collaborations are going to happen again and again, that poets are going to start writing for the theater, where language is going to again inform plot. Because the stage seems to have been adversely influenced by television and the movie industry.

MOLL

By focusing on plot at the expense of the work?

KOMUNYAKAA

And usually it’s a sped-up plot: one collision after another, one mindless chase after another, one bloody scene after another.

MOLL

Every time you come out with a book or project, it feels as if you’ve found something new. How do you keep challenging yourself?

KOMUNYAKAA

Maybe it has to do with growing up in a small town, Bogalusa, Louisiana, where there was always an embracing of something, and in that same moment a moving away. Whatever it was—dealing with it, going through it, attempting to move past it, and then realizing that everything’s connected. We humans possess this great capacity. The human brain is amazing. But it is also gluttonous. That is, it seems willing to almost embrace anything and everything. Perhaps that has a lot to do with how we have evolved and survived as a species.

MOLL

That’s a pretty optimistic view. A lot of people talk about the narrowing of the human mind, with TV and media.

KOMUNYAKAA

The problem with turning on the TV is that one has too many simplified choices. A glut of ball games, comedy shows, soap operas, whatever distraction is on at the moment. The typical American city is a universe of cultivated distractions. But at the same time, there are probably a couple poetry readings in session in the vicinity. Also, maybe a few individuals are trying to write that first line of poetry, or that refrain as a false engine. And not only in America, though I do think the United States is a healthy place for poetry and other artistic pursuits.

DODD

Has it gotten better? In your interview with Vince Gotera back in 1990, you said that the U.S. is a healthy place for poetry, but at the same time—

KOMUNYAKAA

There is a similarity. But also there are some unique voices that pop out. However, I was thinking this morning about the phrase, “between then and now,” and I wanted to place certain poets beneath that phrase. Certain voices. Tonally, each of these voices seems to exist in his or her own world, and yet there’s a shared personality. They’re later than the Modernists. There were a number of names floating around in my head. This thought came to me early this morning. I was thinking of W.S. Merwin, Gwendolyn Brooks, Robert Hayden, Adrienne Rich, Galway Kinnell, James Wright, Alan Dugan, Robert Bly, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, Etheridge Knight, and Donald Hall. These voices. I think this body of work forms a collective voice that’s uniquely North American.

DODD

You’ve written several articles about Hayden and Etheridge Knight. I don’t think Knight’s poetry is celebrated as much as it ought to be, and I don’t know if it’s the politics of his personal life or what’s there on the page.

KOMUNYAKAA

For young poets who aren’t acquainted with Etheridge’s poetry, it is always an engaging surprise for them. He speaks directly to their concerns, without any embellishment or façades. It’s also interesting to think about some of the abovementioned poets who directly embraced Etheridge in friendship, such as Brooks, Bly, Kinnell, and Wright.

DODD

All of whom were doing interesting things on their own.

KOMUNYAKAA

Right. So they felt safe, I think, embracing this man, this poet whose work was different, his personal life entirely different from theirs. They seem not to have been threatened by him. In that sense, this reflects the spirit of the Civil Rights movement, because that movement was truly an American experience accelerated mainly by blacks and whites. Of course, many from different minority groups, especially ones who arrived after those turbulent years, have benefited directly and indirectly from the movement. For many, this is a bone of contention. We only have to look at those thousands of photographs as a reminder of recent history. Just think about those eighteen- and nineteen-year-olds boarding those buses in the Midwest, heading for the Deep South on a freedom ride.

When I was teaching at Indiana University, I used to ask students to look at the photographs of those nineteen-year-olds going south. I said, “Where do you place yourself in this equation? Can you visualize yourself doing this?” Many couldn’t, you know, coming from very safe situations. They couldn’t see themselves stepping forward to help implement change in America. And that sense of change influenced the rest of the world, really. In Australia, I was talking with some aboriginal writers about a decade ago, and they said, “Yes, the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s influenced the idea of change in Australia.” This is true throughout the world.

And at the same time, especially during the 1980s and 1990s, there was a concerted effort to undermine what happened during the movement. That should be analyzed, our need to turn back the clock to the so-called good old days. Do we need to hold a national séance to raise the dead in order to know the meaning of the good old days? I know I don’t.

But many helped to prompt some change, and we as Americans should embrace that recent moment in our history instead of agonizing about it. Because I hate to think about our situation here if the Civil Rights movement had not happened. Indeed, many of those post-Modernist poets were in the bloody mire and sway of the movement.

I remember assigning students to write about the photographs depicting those nineteen-year-olds getting on those buses, you know. Some of those protesters are still in our towns and cities. The Civil Rights monument in Birmingham is dedicated to their heroic efforts. But I think our poetry is also robust enough to embrace that moment in our history.

DODD

Since we began by asking you about “Requiem,” how do you envision New Orleans ten years from now?

KOMUNYAKAA

I hate to think of that tragedy being parlayed into a real estate project, but given that it’s in the United States, most likely the Ninth Ward is going to become a boom area for developers. However, we have to keep the horror of Katrina in our conscience, in our psyche, and we have to make decisions based on that awareness. For years, whenever I went back to New Orleans, I thought, “I’m going to move back here. I’m going to have an apartment here.” That’s the furthest thing from my mind at this moment, because I don’t want to participate in that evil at all.

Also, let’s face it, New Orleans is really a composite of cultures. Of course, that is its uniqueness. The Crescent City was where suburbanites would venture to escape from themselves and do things they wouldn’t do in their own neighborhoods and hometowns. New Orleans was Saturnalia, a place of ancient rituals of harvest and feast. It was one of those places where people probably scared themselves: “My gosh, I’m alive.” We can’t stretch a suburban attitude like gauze over the Big Easy and expect to have the same place. Why did this happen to our most African-influenced city, our Double Scorpio?