Found in Willow Springs 90

JANUARY 22, 2022

POLLY BUCKINGHAM, FOREST BROWN, TORI THURMOND, KP KASZUBOWSKI, AND CAROLINE CARPENTER

A CONVERSATION WITH ALBERT GOLDBARTH

THE WONDER of Goldbarth’s work is in part its wild abundance, its ability to reach as far out as it can and, even within a single poem, move through a dizzying number of written modes and subject matters: quotes from scientists, artists, and writers, snippets of casual conversation, references to pop culture and historical figures, moments of high lyricism, and a certain Goldbarthian chattiness. His work is full of esoterica of the highest order; imagine one of those roadside half-thrift-shop, half-antique-store, half-smalltown- science-museums, and that’s a decent start to an approximation of Goldbarth’s oeuvre. And yet his poems and essays never feel like they exist to show off his knowledge of the things of this world (though his knowledge is staggering); reading them feels more like

reading the imagination at work trying to understand our contemporary predicament with empathy and grace. What makes his moments of deeply felt nostalgia resonant is his relentless attention to the present. Judith Kitchen writes, “Readers who consign him to the category of ‘humor’ fail to see that, as in most good comedy, the poems are a way to bare the pain,” and Lia Purpura writes, “May Albert Goldbarth continue leaving his readers open-mouthed, goggle-eyed, and knocked-out, all of us with our own concussive haloes of stars.”

Goldbarth began publishing books in the early seventies and hasn’t stopped. The occasional two-or-three-year gap between titles is offset by years in which he’s released several titles, including two new collections in 2021/22: Other Worlds (Pitt Press) and Everybody (Lynx House Press). While primarily a poet, he has also written books of essays and a novel, all of which are stamped with his poetic sensibilities. He taught at Cornell and Wichita State University for some thirty years (home of the Goldbarth Archive in Ablah Library).

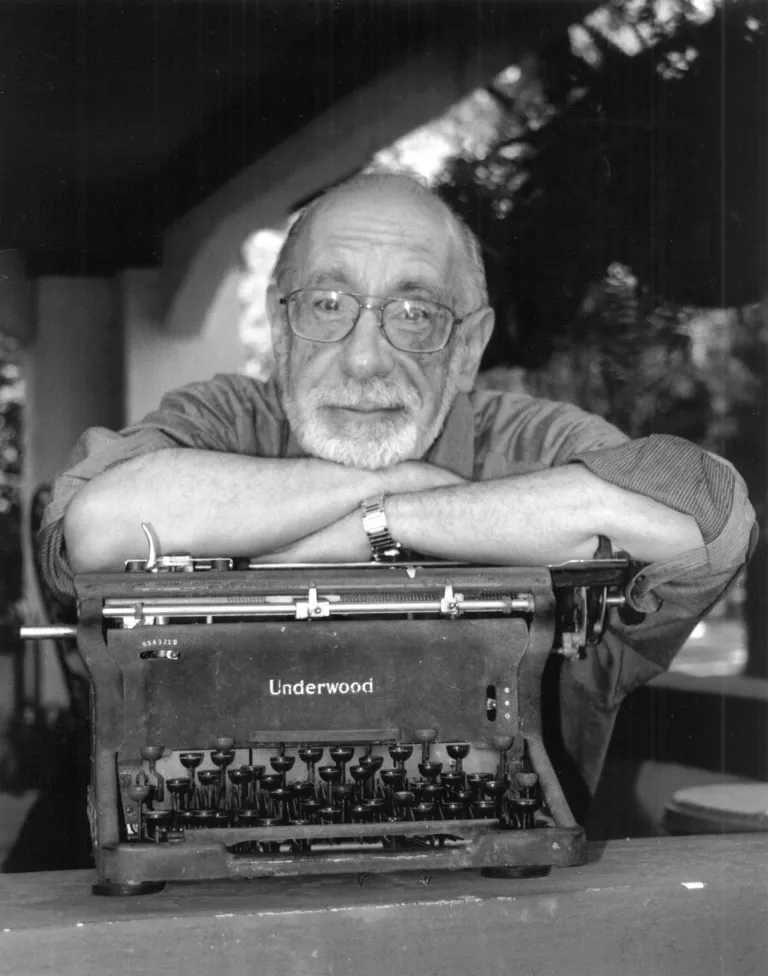

Albert Goldbarth is not a fan of interviews. He would rather write poems than speak on them, and he would rather we read the poems than ask about them. With some fifty books to his name, he’s clearly too busy writing and reading. Surprisingly, he agreed to speak with Willow Springs magazine in a traditional interview. We met him over Zoom on January 22nd, 2022, another first for Goldbarth, who does not own or use a computer; he types his work into one of his many typewriters. Our correspondences were sent primarily through the mail. His wife, Skyler, provided her computer for the interview. In the interview, we talked about the invasion of technology into everyday life, the story of his first text message, his fascination with the obsolete, the relationship between science and the imagination, and the nature of change. We were honored to speak with him, to listen to him, and most importantly, to spend so much time with his work. The poems, of course, speak for themselves.

POLLY BUCKINGHAM

Okay, we’re recording.

ALBERT GOLDBARTH

All right, I’m the old man in the corner right there.

Warning: I don’t think I’m good at interviews. I’m always amazed when I read other people’s and see how eloquent and fascinating they are; it seems I pour everything into my poems. There’s nothing left over for occasions like this.

BUCKINGHAM

I finally read the “interview” you did with the Georgia Review, and I was like, “Well, why are we here? It’s all in there.”

GOLDBARTH

I have to admit, I was proud of that “interview” when I finally finished it. At the start, I wasn’t sure it would work. It was part of this special feature the Georgia Review did. The whole thing must be maybe sixty pages long: twenty-six pages of my poems, a couple of pages of my original handwritten manuscript for one of the poems, two essays on me, photographs that Skyler took, et cetera. And then the editors wanted to do an interview, too, which was not an unreasonable request. And I didn’t want to do it. They asked again. I really didn’t want to do it. Finally, I thought, “Well, I believe in poems, not interviews,” so I said, “What if all the questions come from other poets’ poems and all of the answers come from poems of mine?” I had no idea which specific poems might match up seamlessly as questions and answers, but by the end I thought it worked out. I was hoping it would become the role model for all poets’ interviews in the future, but [sigh] that doesn’t seem to have happened.

FOREST BROWN

I love the way that you were able to engage with other poets and your own poetry for the interview. I wonder if that’s something you do outside of that project or if that was just a one-time thing.

GOLDBARTH

Outside of that “interview,” I’ve never committed anything to a written format in exactly that way and published it, but sometimes I get together with my friends, and we’ll read poems out loud, poems we’ve encountered recently on our own that we think are worth sharing. Do any of you know Richard Hugo’s book 31 Letters and 13 Dreams? I don’t think it’s his best book, but it’s a lovely concept, trying to come up with language that would work as poetry in a published book or journal publication but that also works as actual real-world letters that he really sent out, postally. I appreciate ideas like that, poetry working in the real world and people communicating through poetry.

I still send postal mail to friends on a weekly basis and get postal mail on a weekly basis back. Every week my friend John from Texas sends me a letter typed on a manual typewriter, and we will clip things from magazines and newspapers for each other. Sometimes just the naked clippings. Sometimes we’ll doctor them in funny or otherwise interesting ways. It arrives, you open it, and it’s a meaningful, real-world weight in your hand. It has the impress of a human being’s breath and body behind it. It’s lovely. We’ve been doing this for decades.

I think the postal service represents, in some ways, America at its best. I still go to the post office, my local substation, two or three times a week. My own letter carrier is a woman named Nancy. She’s smart, she’s sharp, she’s funny, she “gets it.” I enjoy talking to her on the porch and typing up little postal related things or photocopying USPS-related anecdotes and leaving them for her on our mailbox. This week I heard postally from my old Chicago friend Wayne, and from poets Alice Friman and Larry Raab . . . the charge of their fingers was still on the paper.

TORI THURMOND

Quite a few of your poems start with research. I wanted to ask where it comes from. Is it while you’re reading you get an idea, and you want to base a poem off that? Or is it the other way around, where you get an idea for a poem, then go research it and pull some of that research in?

GOLDBARTH

Over the course of my writing life, both have occurred, but it seems healthier if I’m simply reading for pleasure, not specifically trawling through things just to find an idea for a poem. I’m reading something, and, bingo, that day or three years later, a little light goes off in my head, “Oh, yeah, I’d like to explore this.” To that extent, “research” sounds too calculated in its implications. Oh, there’s some research of course; but often it’s more like being open to a timely shout-out from my memory storage, my muse node.

BROWN

I had a question about the balance between inspiration and research. I thought of the balance between Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer in some of your work and how they’re connected, but one is more scientific, one more artistic. I wonder if you feel you owe a loyalty to one of those disciplines more than the other.

GOLDBARTH

In my introduction for a book about the sciences and the arts, The Measured Word, I try to address the state of science and the arts back in, let’s say, Wordsworth’s day, Coleridge’s day, when there existed a language that scientists and artists shared. I think they also shared a sense that they were involved in the same pursuits, the pursuit of knowledge in the objective world and the pursuit of knowledge of the self. The well-known scientific researchers of that day read literature and tried to write it themselves. The quest was similar, whether you were a geologist, chemist, Wordsworth, or Coleridge. There’s a famous moment when Coleridge and some other writers allow themselves to be put under what we would call laughing gas in a serious experiment to see how it affects the human psyche. They all wind up floating on the ceiling, getting high in the famous evening’s endeavors.

C. P. Snow wrote an influential book, The Two Cultures, about the disappearance of that communal endeavor, which explores the growing realization that artists and scientists do not live in the same universe any longer and do not share goals or language. I think, on the whole, my head exists back in the world when Coleridge and Humphrey Davy, the chemist, shared a single pursuit and a single vocabulary. A lot of the leisure time reading I do, reading that’s not simply an adventure novel, is work that credits both sides of the divide, to the extent that I can understand the science part at all. In my head, Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer are equals no matter the differences in their lives and their passions. They are essentially siblings, twins separated at birth, similarly and equally involved in attempting to answer the question, “What does it mean to be a live human being in this cosmos?” As I loosely remember, in my essay “Delft” I try to give them equal weight, I mean actual paragraph by paragraph equivalency.

BROWN

With so much of your work dealing with these sorts of characters and also with science and research, how do you feel about obsolescence?

GOLDBARTH

I think it’s my nature to want to eulogize what’s passing more than see the beauty of the transmutation. I understand everything needs to disappear. There’s only a finite amount of matter and energy in the universe. It has to be kept in revolution all the time. I understand you don’t get to move ahead unless you see the world in the rearview mirror diminishing. But at the moment, it seems to me the future, especially in terms of technology, is colonizing the present moment at a dangerously ferocious rate. It feels right that there should be some people who want to put the brakes on, halt that process to a small extent. There’s still a past that we have not happily used for all its pleasures and lessons. And it’s worthwhile for me to stand still for a moment, turn around 180 degrees, and further embrace what’s disappearing before we make the other turn around and face the untested wonder of tomorrow. There’s a beauty in that, and more and more, I think culturally it’s necessary to let the past live on . . . in TV terms, to replay in syndication.

Think of all of the things that were happening in 1913 in a wealth of realms. Harriet Monroe founds Poetry magazine, Edgar Rice Burroughs is publishing the first Tarzan novel and the first great John Carter of Mars novel, the Suffragist movement is doing fascinating, seminal, and brave things politically . . . there was the “Armory Show.” That year seems to be a watershed year that not only allows a number of what we might see as very disparate fields to make very important kinds of advances, but, again, as with Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer, it’s interesting to take the people involved in these discrete movements and see them, at our remove, in a way they might not have seen themselves: as equals working at a certain zeitgeist-cohesive moment of time. I don’t care to abandon that just in the interest of adding a new app to my phone. And, yes, I know it doesn’t have to be “either/or.” Still, our loyalties make themselves known as we choose how to parcel out our affection and attention.

BUCKINGHAM

In an article by David Wojahn, he talks about work that’s based on a Google sound bite versus broader research. He uses you, and he shows an example of a poem from Everyday People. It’s clear when I’m reading it that these aren’t just sound bites; this is stuff you’ve read thoroughly. I guess that’s one reason why none of this feels obsolete—because it’s placed in the context of a constantly changing world.

GOLDBARTH

It was a sweet piece by David Wojahn (himself one of the master poets of my generation), and of course I appreciated its sensibility. If I remember his language correctly, he draws a distinction between the poetry of “knowledge” and the poetry of “stuff,” between factoids grabbed on the run from Google scrolling, and knowledge gained from deeper reading; knowledge that doesn’t get paraded in a poem for its surface “interest value,” but gets constellated with everything else that’s been already incorporated into a writer’s understanding of the world. It’s common to try to differentiate between “knowledge” and “wisdom.” Wojahn reminds us that, particularly in our cultural moment, we must differentiate “knowledge” from “data.”

His essays have been collected in book form, and are themselves—like his poems—fine examples of the best use of deep, empathetic knowledge. Wide ranging, but also rooted in long-term contemplation. And while they can use, they don’t depend upon, the self-congratulatory mumbo-jumbo of academic lit crit terminology: they remain human. (I used to lecture on a Whitman poem, “The Sleepers,” for six hours, spread over two class sessions, unpacking it line by line, often word by word, without relying on lit crit “scholarship”. . . it was the reading, I’m certain, that Whitman himself would have wanted, derived from the poem, not forced on it from the outside.)

I own a number of books on what’s gone out of existence, become obsolete, in your lifetime and mine—all of those things, like the smell of burning autumn leaves, gone from the outside landscape; analog clocks (the very objects that give us “clockwise” and “counterclockwise”), gone from our inside landscape; and the pleasures of brick-andmortar bookstores and library shelf browsing, gone from our psychic landscape. I guess I’m someone who doesn’t automatically find “nostalgic” to be a pejorative descriptor. It can also imply an honorable stewardship of what’s endangered. I don’t particularly read steampunk science fiction, but its feel, of striding into the future without discarding the look and knowledge of the past, certainly has an appeal.

Some of the typewriters I’ve collected (and typewriter accessories, like gorgeous deco-design typewriter ribbon tins) by now have a magical aura around them. And I wish I could show you the Oliver typewriter from 1913 (there’s that year again!), with its keys arranged in a bowl shape like the audience in a round amphitheater, and its gilded lettering. No wonder some young people I know, half my age or less, have taken to collecting them. My arts-minded friend Joey sometimes types a poem, using a manual typewriter, on a four-by-six notecard—a “one-off” in the truest sense—and distributes it into a book on a local bookstore’s shelf, counting on chance to deliver it into (maybe) the right hands. This isn’t going to get him the National Book Award, but who could be blind to the beauty of that act?

I don’t collect antique fountain pens, but my friend Rick Mulkey does, and I know that when I join him in a few weeks in St. Louis at a fountain pen show, my eyes will be popping with a respectful wonder. Another old friend, the poet Bob Lietz, collected those pens (and taught himself to repair their nibs and ink bladders) and wrote an ambitious sequence of poems in which he gives voice to the pens during their lives of active use, creating a heartsore love letter from a World War I soldier overseas or a harsh sentencing coming down from a small-town “hanging judge.” Giving voice to the departed (and their world) seems to me a secular blessing.

BROWN

I noticed, in a lot of your books, your love for Karp’s In Flagrante Collecto.

GOLDBARTH

Yeah! It’s filled with jaw-dropping images of objects from once-upon-a-time and with a sense of the passion behind their being conserved. You know, some of those things we can wave goodbye to happily enough. Do we need Junior League meetings where everybody’s wearing white gloves? Maybe not so much. Kotex? Maybe not so much. I guess we each get to choose for our personal list of what’s a keeper that gets shelf space and what gets boxed up for Goodwill. I find it a little painful to realize nobody knows what carbon paper is any longer. It also makes me realize, and I don’t want to get too self-pitying, how much of my poetry really would not be readily comprehensible to many younger readers. Just a little while ago, I was talking to a friend of mine—I like him a lot, he’s witty, talented, he’s sharp, he reads, he’s about forty years old—and I made a quick reference to the heads on Easter Island. He had no idea what I was talking about. Not only could he not picture the famous heads, he had never heard the name Easter Island. Ditto Speedy Alka-Seltzer and Elsie the Cow. My work is filled with allusions to objects, people, events, places that are obsolete. At some point, if I can pretend my work would be read in the future, it will be read completely comprehendingly only by people who are looking things up every fourth or fifth line as they continue through the poem, which, of course, is not reading the poem as the poem wants to be read. Years ago, and I’m talking maybe twenty-five years ago, a poem of mine appeared in some textbook anthology, Groovy Contemporary Poets: Here They Are, something like that, and I was shocked to discover that there was a footnote explaining what Coors beer was. And there was a footnote explaining who Flash Gordon was. Painful for me, just painful, and that was a quarter of a century ago. Imagine now.

Do you want to hear the story of my very first phone text?

I never wanted even this little flip phone. I was sure nothing like this was going to be part of my life, but there came a time when Wichita’s sickly famous serial killer BTK, which stands for bind, torture, kill, emerged again from under a rock after a long hiatus. The fear engendered by 9/11 was also in the air. My wife was teaching at one place, and I was teaching at another place forty-five minutes away from hers. I thought, well okay, even me, just for emergencies, I’ll get one of these gizmos so my wife and I can stay in touch if we really need to, or, if we hear a noise downstairs, I can hit 9-1-1. So I hesitantly bought one, and for a long, long time, I didn’t use it. I didn’t have any names in my phone book. I didn’t know how to, or care how to, send or receive a text. In fact, most people I knew didn’t even realize I owned one. They didn’t have the number, and they wouldn’t have tried texting me even if they did have the number.

The poet and essayist Lia Purpura, a vastly talented woman younger than myself but sharing some of my sensibility, was with a friend of hers in Baltimore one night. Don’t take this as gospel, but I think alcohol may have been involved. The girlfriend said something like, “I’m going to teach you how to text,” and she said, “No you’re not, I don’t want to know,” “Yes girl, have another drink, I’m going to teach you how to text. Who do you want to send a text to?” “I believe I’ll send a text to Albert.”

So it’s midnight here, 1 a.m. for them. I’m driving around the streets, and I hear my phone make a sound it’s never made before, some kind of alert beep. I take it out of my pocket, and the phone must say something like, “Incoming Text” or “Text Just Arrived” because I wouldn’t have recognized what the sound meant. I pull into the lot of a closed-down gas station to see what this is all about. I manage to hit the right little key that calls up her text, and I remember saying to myself, “Ah-hah! I’m going to teach myself to text her back.” I stayed for forty-five minutes at this closed gas station until I was able to send some snarky sentence or two back to her. So there, Lia! There was no turning back as you know. It’s how technology works. It colonizes. There are now like 800 people in my phone book, whether I want them there or not. Heck, Polly’s in there.

BUCKINGHAM

I run across this dichotomy in your work a lot. You’re so flexible, embracing change, and yet at the same time there’s this important stuff of the past. I come back to the quote from your newest book, Other Worlds, where you say, “I want to be unwilling.” You also very much embrace popular culture. Could you talk about your obsession with pop culture and how it resonates for our cultural identity?

GOLDBARTH

This is my phone. [Holds up his flip phone.] I’ve never touched a keypad that isn’t this type of keypad. If I were to text you the word “Moonlight,” I would have to tap down sixteen times: one for the M, then three for the O . . . So that’s what I’m dealing with. That’s my chosen world.

In the sense in which you’re using that line from my poem, I’m “unwilling” to use a more super-duper model.

About “pop culture knowledge” versus “serious knowledge” . . . Once when I was still living with my parents in a little condo, our upstairs neighbor, Ellie, came down and asked me to talk to her two young girls and convince them to go to college. They wanted to be juvenile delinquents or buskers, or ballerinas, or whatever. She wanted them to be “successful” and make a “good” living. I remember trying to convince her that you should want to know things from the pure delight of knowing things. There’s a great joy in that, and a pure joy. Purity of that kind is important. I still like to believe my writing is not a career but a calling. I’ve been paid to give readings, but I work hard to make my writing a calling as I think it was, say, for Keats, who never went on a reading circuit, who couldn’t have imagined such a thing.

In my head there’s not always a great deal of difference between popular culture knowledge and the knowledge of science, politics, serious cultural studies. It’s all what I called “the delight of knowing things.” I know there’s a difference between reading an Edgar Rice Burroughs Tarzan novel and Foucault, I really do. But they’re both up there in my mind trying to have a voice in my life and be part of who and what I am.

Have any of you ever read The Reluctant Dragon, a children’s book by Kenneth Grahame, who did The Wind in the Willows? It’ll charm the socks off you. The epigraph to the book reads, “What the Boy chiefly dabbled in was natural history and fairy tales, and he just took them as they came, in a sandwichy sort of way, without making any distinctions; and really his course of reading strikes one as rather sensible.” To repeat a term I used earlier, it all gets “constellated” into a single connections-making sensibility. So long as one doesn’t fall down a QAnon rabbit hole or start truly believing the Earth is flat, all knowledge should provide a field to romp joyfully in. In any case, I use the Grahame statement as the epigraph to my book Arts & Sciences. It’s a banner I’m happy to wave.

KP KASZUBOWSKI

I just finished Pieces of Payne. The premise of the book is that you’re having seven drinks with a friend, a former student. That’s making me think of your story with the friend who learned how to text by texting you. I’m curious: what is fiction and what is not?

GOLDBARTH

I thought you were going to ask how often I go out for seven drinks with people. That can be for another interview. I’m not comfortable with the question of what’s “true” or “isn’t true.” I like to say, not just for myself but on behalf of all poets, it’s all true. I mean in the way that a real novel is as true as a piece of nonfiction or memoir, as true about human beings and the human experience. Perhaps even truer than some memoirs, in fact. Memoirs are also fictionalized—by the time it’s a readable, publishable piece of work, it’s all become fictionalized, massaged to some extent. Truthfully, although you can find many poems of mine that refer to a character called Albert, who maybe lives in Wichita, who maybe has a wife named Skyler, I don’t ask that any of my work be taken as autobiography.

There have always been lyric poems arriving here straight from the poet’s heart: think “Summer Is Icumen In.” But it’s easy to forget how drastically things changed with the relatively recent generation of “confessional poets” like Lowell and Sexton and Snodgrass, and with the Beats; easy to forget that for the longest time poetry was defined at least as typically by, say, Paradise Lost and “Endymion”: poems that in intent are true about the human condition, but the innards of which were—like a novel’s innards—based upon invention. I talk with people frequently who are not perplexed to read “Call me Ishmael” even while finding the name Herman Melville on the cover; and yet who are surprised or even offended if I suggest the possibility that Plath might have invented, have shaped events for some of her poems, in the interest of their greatest possible power or her own greatest psychological needs.

BROWN

I had a question not about autobiography but biography. I really like one of your lines, “A paleontologist could step inside and be surrounded by images of life but no life.” Whether it’s with a fictionalized idea of yourself or a character or people in the past, how do we, or how do you, like to see aspects of life that we can or can’t put into poetry? What can we portray in that way versus what just has to be lived?

GOLDBARTH

Well, poems ought to be able to include, and in fact do, anything they want to. It’s poetry, after all, and should be a bastion of pure creative freedom. If you can’t include anything you want or exclude anything you want in your own poem, something’s wrong.

This is going to be a reductive example as part of my answer, but: all of those things we’re calling essays right now, I originally tried to publish as poems. They felt like poems to me, and I think of myself as “a poet.” They happen to be in paragraph form since sometimes paragraphs are, for various reasons we could talk about, a more sensible or useful holding container for the kind of writing that includes characters, dialogue, research material. But in many ways, they didn’t feel any different to me than my poetry did. In fact, I thought it added interest and value to consider them as poems instead of essays. The longest piece of prose-looking writing I’ve ever done, perhaps even including my novel Pieces of Payne, I’d be willing to still think of as a poem. I would defend Moby Dick as a poem any day if you gave me time to think about it and make notes. But no publisher was willing to publish them as poems, in part because they believed they would sell better as books if they were essays, though (and I’ll sigh again) that’s never turned out to be the case.

For journal purposes, it was an easier (and editors might have seen it as a more forthright) way of including work in a table of contents or an end of the year index. My first book of essays was called A Sympathy of Souls published by Coffee House Press. At the time, Alan Kornblum was still alive, the founding editor. He was the one who accepted and edited the book. I remember quite clearly an exchange we had, a postal exchange, in which I kept trying to defend the book as a book of poetry and in which he finally said, and here I’m quoting many years down the line, “Albert, what do you want to shoot yourself in the foot for?” So it was published as a book of essays. Evidently, I don’t have a marketplace mentality. I guess I’m implying the simple idea that the wrestle of “real-self self” with “fictionalized self” can be played out even in decisions on determining genre . . . and that a writer’s claim to absolute authorial freedom can be laid out in that arena, too.

THURMOND

I like that idea—let the poem be what it wants to be, or a poem can be whatever you want it to be. I noticed how your long poems are sectioned throughout the collection. Some sections will be lyric poetry, some will be sections of prose, and then some even dialogue. The poems shift from one thing to another. Is that something you’ve always been experimenting with, or is that combination of form something you came into later?

GOLDBARTH

I’m not sure that after James Joyce and Gertrude Stein, I count as an experimentalist in any major way, but, yes, not all of my work consists of “standard” lineated lyric poems. Even some of my earliest pieces include the idea that a lyric poem can modulate into, or break and become, something that replicates the scholarship of archaeology or anthropology or quote overheard dialogue or newspaper coverage, or take on the form of a play script . . . and then move back into a more rhapsodic, lyric mode. That doesn’t seem strange to me. I like to think, at my most honorable, I’m not sitting around thinking, “Oh this’ll be attention-grabbing, this will show them what I can do, hey look I can do five modes here, take that,” but that instead it’s a holistic expression of the needs of that particular piece of writing. Pieces of Payne is about two-thirds endnotes. There’s the actual straight, novel-like narrative and then footnote-like numbers throughout. I don’t know how you read it, but the idea is you can read the pure narrative all on its own without going to the endnotes as their own cohesive entity, then read the endnotes, or you can flip back and forth and read the narrative and the notes in tandem, a kind of build-your-own-adventure book.

Anyway, I’m offering Pieces of Payne as a book-length example of the kind of “hybrid form” freedom we’ve been talking about. There’s a special issue of The Kenyon Review from Spring 1990 that I guest-edited devoted to what the editors called “Impure Form.” And the anthology American Hybrid edited by Cole Swensen and David St. John presents a very liberal understanding of what a “poem” can be.

CAROLINE CARPENTER

Would you be willing to talk about the immigration experience in your work and your family?

GOLDBARTH

Well, isn’t it a generally accepted idea that we’re all immigrants here, one way or another? Ever since the early hominids left the vicinity of Olduvai Gorge, isn’t everyone from immigrant stock? Even the very first Native Americans came over the land bridge from Asia (though, of course, without displacing anyone). So I don’t know that I have any particular insights. If you’ve read some of my work that deals with it, you would understand that I am a third-generation American Jew. There was a generation of European Jews who came over and wanted to do nothing but leave all of the misery behind and blend in and become good Americans. Parts of that same generation came over and held on to a kind of political fervor, became socialists, became Wobblies, were very politicized. Families broke apart over that divide. My father and mother just wanted to raise a happy safe family and blend in as much as possible, without abandoning a respect for Jewish tradition and ceremony. There were people on the other side, relatives who lived in Chicago where I grew up, who I never met. You see that divide in other cultures, too. I’ve heard stories similar to mine from people—the Mexican tradition, Iraqi tradition, on and on.

My parents were very lower to middle-class Chicago people, not sophisticated at all by many standards, certainly not college educated. They played poker with their friends. My mother read paperback mysteries. My father probably only read the newspaper, and that was it. I know they were naturally bright, but they were not bright in terms of cultural sophistication. At my father’s funeral, my sister and I were sitting in the first row at the synagogue service before we all reconvened at the cemetery. I look around and there are all these tubby Chicago Jews. They’re wearing suburban car coats they got on sale somewhere. They’d be eager to tell you what a bargain they got, too. That was their sensibility. They were straight from the nickel-bet poker table or an overheated kitchen. As I’m looking around, this couple about my father’s age walk in. They’re tall and thin and elegant. These people look like fashion models. He’s wearing a kind of butter-soft Italian hand-tailored leather jacket. She has long, straight, elegantly gray hair. Like Mary from “Peter, Paul, and Mary” in later life. They absolutely don’t belong there. I’ve never seen them before, but there they were at my father’s funeral. Later, I’m talking to my sister and I say, “Who were those people?” She said, “Oh, they’re from the other side of the family,” which is to say, the more politicized side. “He’s a painter,” she said, and I knew instinctively she did not mean a house painter. He was an actual “artistic painter.” When I was a little newbie poet in the family, I was given no idea there was an artist on the other side.

My father tried to keep up a certain sense of religiosity in the household. He also believed in earning a living and making a safe American life for his family. So, for instance, we would celebrate all the major Jewish holidays—we’d light candles, go through prayers, we had a real version of a real Passover seder—but if he needed to, he would work on a Saturday, which of course, Jews are not really supposed to do. It’s the Jewish Sabbath. He would only eat kosher meat and never mix meat and dairy, but he would go out and eat a limited number of foods in restaurants, which a truly Orthodox Jew would never do either. So he made his own, nuanced way through a combination of religiosity and accommodation to the world as it was presented to him.

BUCKINGHAM

I was reading “The Window Is an Almanac” from Who Gathered and Whispered Behind Me. I love Rosie, your grandmother in these pieces. I wouldn’t mind hearing more about your relationship with your grandparents because I like them as people already in your work. Also, there’s a lot of Chagall in there. I wondered about the role of art in your life and your work. You mention artists of light, Vermeer and Chagall.

GOLDBARTH

That poem, as much as I can remember it from a book published in 1981, mixes and matches the study of Chagall’s stained glass with more lyric memories or pseudo-memories of Rosie and my grandparents’ generation. When it ends, she’s dead already, but she kind of mystically appears in the light that might enter through a Chagall stained-glass window, almost as if she takes my hand and I walk together with her, and we converse. The poem takes its cue from Chagall: “Stained glass is easy. The same thing happens in a cathedral or a synagogue: a mystical thing passes through the glass.”

CARPENTER

I wanted to ask about the choice behind naming real life people in the poetry. Most contemporary poets I’ve read refrain from actually naming people who exist in real life. A lot of times, poets will just use initials. But you name them and give them their justified moment on the page. What, if any, power does it give the poem to name the person specifically?

GOLDBARTH

Contemporary poets don’t use “actual names”? Go figure. Maybe the world becomes increasingly litigious. Anyway, I’ll use a “real name” (as I would an invented name) if I think it’s in the poem’s best interest . . . and I’d like to think I still count as a contemporary poet.

I think there’s a power in names: we can see that in everything from tribal ritual, oaths, curses, vows, to lawsuits and rap battles. I try to access that power, although “My friend Doris” in a poem doesn’t necessarily mean in “real life” I have a friend named Doris. Hopefully, as I’ve already said, “the poem” is true to the human condition; but I may have been more interested in how the “d” ending “friend” and the “d” beginning “Doris” make an aural unit. As I said earlier, even what we receive as autobiography and memoir is normally shaped toward certain aesthetic ends. It’s like the difference perhaps between the past and history. The past is its own incomprehensible, unchangeable thing. History is what we make of it. And naming can bestow a poem with the power of authenticity.

In Galway Kinnell’s The Book of Nightmares, a book length poem I still think is one of the high watermarks of poetry in his generation, there’s a moment when he refers to himself in the third person. He says something like, “Look, Kinnell,” and then he reads himself a small riot act or gives himself a small bit of hard advice. It anchored that moment in a particular kind of believability that it might not have had otherwise. A little later on, a very widely published poet of my generation, perhaps not on people’s radar screens much anymore, Greg Kuzma—he might have been for a while the most widely published poet of my generation in the literary magazines of the time—his younger brother died, I believe in a car accident, and you could tell they were close. You could tell it was a loving brotherly relationship and Kuzma, this man for whom poetry might have been the single most important thing in his life, starts a poem, kind of an elegy for the brother, by lamenting (and accusing), “Galway Kinnell, where were you when I needed you? Bill Merwin, the same.” It becomes a very heartbreaking poem about how even for somebody who loves poetry down to the innermost molecule of his being, there are times when the poetry fails you, even the poetry of some of its wisest practitioners. “Where was Diane Wakoski in her charity, / or Donald Justice of the gentle hand?” There’s Kinnell referring to himself as Kinnell, and a decade later there’s Greg Kuzma using Kinnell in his poem. Both poems profit from the name.

BUCKINGHAM

I was happy to see Robert Bly and Tony Hoagland mentioned in Other Worlds. This would have come out before Bly died. It was a nice surprise.

GOLDBARTH

They were both major, important voices. Bly simply because he was Bly. Absolutely unduplicatable. He just did so much and did some of it so well. The poems, the very thinking, of my generation are different and better for him. He has a poem called “The Buff-Chested Grouse” in one of his later books. The first line of that poem has always resonated with me, and I’ve always been looking for an excuse to use it as an epigraph to a book. It says, and I know I’m quoting word by word, “I have spent my whole life doing what I love.” I think if a poet can say that by the end of his life, it’s a beautiful self-benediction. And Hoagland was good. He was a big poet, an exemplar of how a seemingly casual free-verse voice can be strategized toward effectiveness; a man of deeply tender and complicated feelings; a sly humorist; and someone formidably honest in his dissections of the best and the worst in us. He was very honest about the way he saw human beings. I assume he’s been in the magazine in the past.

BUCKINGHAM

Yeah, I think so. Bly did an interview with us, not when I was here, but he’s among our interviewees

GOLDBARTH

You know, speaking of that . . . I’m not crazy about interviews. I’d love to hijack the questioning now, and talk about how I think interviews are absolutely beside the point. One of the reasons I finally talked myself into doing this was the great list of honorable names that had been part of Willow Springs interviews in the past. I know Bly was part of it long ago. I reread Joyce’s [Joyce Carol Oates] interview. So yes, I know that I’m a little part in a list of grand presences. Still, and with no offense meant to you and the amount of homework you did leading toward this moment, I’m left thinking: if a writer is worth his or her salt, hasn’t he already told me what he really wants to in his or her fiction, in his or her poems? Life is short. I’m going to be seventy-four on Monday. When I open an issue of Willow Springs, shouldn’t I be reading the literature itself, the Real Deal?

Here’s a dictum: If it was good enough for Keats, it’s good enough for me. I think Keats is a great poet, I think I’m a good reader of Keats’s work. (I have an essay I like very much that pairs Keats with Clyde Tombaugh, the man who discovered Pluto at the Lowell Observatory.) I’m sure he was not sitting around when he was writing “Ode on a Grecian Urn” and thinking, “Oh God, I only wish there was something like a reading series where I could belt this out loud for people and then they could ask me questions afterwards—let’s call it a Q & A session—and I could hit on somebody, and they would take me to dinner.” He thought the poem itself was enough, and for the right reader it is, and I think I’m a “right reader” for Keats. I will never obviously hear him read his poems. I’m sure she’s probably been taped, but I’ve never heard Toni Morrison read her fiction, and now I never will. I’ve never heard either of them give a “craft lecture.” The phrase would be meaningless to Keats. But I know how to read their work. The other stuff (cue in this very interview), really, is only diverting, is mere chatter, and is nobody’s business. And yet here I am, being interviewed—and in the face of your friendly interest, inveighing against interviews. (“I know! I’ll use the interview as a Trojan horse, to attack the enemy from inside the gates!”) I have no excuse for seeming so passive-aggressive, except that one can’t slam the door in the world’s face every time it knocks. Hopefully, one selects the right knocks to answer. Polly and the magazine seem like one of those “right knocks.”

Often, lately, there’s more time devoted to the Q & A at a poetry reading than to the work, the primacy, itself. I fight against that. A number of years ago, the magician David Copperfield performed Wichita. My wife and I went, an amazing show. There’s a moment where he lifts off from the stage and flies over the audience. Flies right overhead. You can see there are no wires; you can see there are no mirrors. He flies over the audience. What he doesn’t do is come out from behind the curtains afterwards and say, “Okay, a Q & A session now.” Audience member lifts hand: “Hey, that’s a great trick. I’m studying to be a magician. I’ve got some magic tricks in my back pocket I could show you before you leave. Could you tell us anything about how that trick was done or why you even thought to create it? What does flying mean to you?” None of that. He performed the primacy. It was awesome. He’s given the best of what he is, the best of what he has to offer. He’s devoted how many hours to that effect? Hundreds to get that down right. Maybe more than hundreds. It was like watching the voice come out of the burning bush. That’s all that’s required of him. Why would anybody want to spoil it by knowing how it’s done?

So: magic. I think I read other people’s work hoping for magic to strike. As an example, let me use a poet you may know of, Lucia Perillo. From Oregon. She was a wonderful, honorable writer, I reread her frequently, and, as a side note, she dealt with her MS in honorably courageous ways. Gone from us now, way too early. Now I’ll digress for a moment. I remember my eighth-grade English teacher Mrs. Hurd saying, in her little-old-gray-haired-itty-bitty-lady voice, “Anytime you open a book and read it, that writer lives again.” She said it as if it were the most important wisdom she had to impart. So Keats is alive for me. Toni Morrison is alive for me. And Lucia is alive for me through her books. It’s a mitzvah to revive her, for my reading mind to give her breath again. And when I read Lucia at her best, I don’t find myself most immediately thinking, “Oh, that was a clever move” or “I bet this woman voted the way I vote” (although such thoughts may also come, down the line). No, I’m thinking, “Jesusfuck, how did she do that? I couldn’t do that.” She’s a good enough poet to gift me with that amazement: not many are. And that’s the moment you read for and the moment you hope against hope might be in your own work on occasion. “How did he do that?” The magic. The flying.

If I could make Lucia alive again, I’d be happy to go out for drinks with her in that “seven-drinks place.” I’d love to talk about all sorts of things with her. You know, politics, sports, food, gossip, why are guys jerks, why can’t women find their keys in their own purse? I’d love to talk to her for hours, but I bet we would not ask one another “interview questions” at all. “How’d you do this?” “Why did you?” “Where’d you research?” “How much is real, how much is invented?” We would just be people for one another. The one time I did meet Lucia—she hosted a dinner for me at her home—that’s how it went. The one time I dinnered with Toni Morrison, we talked mainly about Conan the Barbarian and Red Sonja comic books.

The poet Richard Siken, I think this was before he published his first and very highly regarded book, interviewed me for one of Poetry’s online thingamajiggies about my collection of vintage space toys. He seemed to have his own honest interest in understanding that world of collecting. Although you’ve heard me talk now about what I think of writer interviews, that interview was about the toys and the collector’s instinct. I didn’t mind that interview at all.

I’ve worked diligently all my life in hopes of making my poems meaningful—moving, useful—to other people, and building them solid, to last. They in fact may not be meaningful for given reader X or Y (okay, fair enough), and I don’t know that the culture will move them on into the future. Still, that’s the hope. You may hope that for your own writing, too. But this interview? . . . I don’t mean to insult either you or myself (our intentions are surely good) when I say that it’s ephemeral chat, a small momentary bubble drifting away on the 24-7 litbiz torrent.

KASZUBOWSKI

In this spirit of not asking you about craft then, I came across a poem where you said you were a psychic. Can you tell me about how that happened for you and what that is in your life?

GOLDBARTH

Oh, that’s right! I’ll try to recap what leads to that line in the poem. My wife, or the woman somebody calls his wife in the poem, goes to her beautician, a woman named Lateena. She’s doing the wife’s hair, and some special occasion is implied by the fact that my wife is getting her hair done. The beautician asks what special event is coming up and the wife answers, casually, “Oh, my husband’s giving a reading.” Lateena whaps her forehead in astonishment at this news, this amazing revelation, and says, “Oh! Your husband’s a psychic!”

That’s the comedic setup; the speaker goes on to say, “Oh yes I am.” And he means this not in the sense of a carnival psychic in a hokey turban and a starry robe, but in the sense that real writers—let’s bring Keats and Perillo and Morrison back for a sec, let’s throw in Jim Harrison—indeed know the human condition well enough (even if intuitively and not consciously) to make illuminating assumptions about us. With an inflated sense of self and a dash of humor, my poem risks adding its speaker to that company.

Sometimes I’ve said in conversation, “You know, there were poets before there were shrinks and therapists, before there were priests and ministers and rabbis, and there will be poets long after.” When I was teaching at the University of Texas in Austin, this must have been forty years ago, I had a student in my class, Karen Earle. She was very bright, a little older than the other students, very likable—I was really pleased she was in the course; she made great conversation. She was a psych major. I’m always particularly happy when I see people in workshops who are not English majors or creative writing majors, who happen to be good writers and love reading. Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath came up in discussion. Students used to ask in those days, “Why do so many poets commit suicide?” to which I would often say, “Do you know how many plumbers commit suicide?” Anyway, this idea seems to be out there: why are so many poets in therapy? Karen, who planned on being a therapist, raised her hand and said, “I know there are a lot of poets who have gone to see therapists, but let me tell you: it would be a better world if more therapists went to see writers.” If we’re talking about “real writers,” and not just accumulators of CV fodder, I think that’s true. There are worse things many therapists could do than sit down and read a Jim Harrison book.

BUCKINGHAM

At the end of Other Worlds you say, “I’m lost, I don’t feel,” or the narrator says, “I’m lost, I don’t feel.” I appreciate the validation that it’s okay to be lost, it’s okay to scream, it’s okay to be unwilling; I think the book is very guiding for us.

GOLDBARTH

My friends tend to be the kinds of people who regret the disappearance, as I’ve already said, of real-world browsing in brick-and-mortar bookstores and libraries—of willingly “getting lost” in the interests of discovering some unexpected treasure. I understand that one can also “get lost” in the online infinitude—in fact for many reasons the powers behind the internet are counting on that—but I still think the very terms “search engine” and “Google search” imply a desire for direction and limitation. Nicholas Carr’s important book The Glass Cage has a section on what disappears—not only attitudinally but in terms of actual neural capability—when we rely on GPS, and not on our brainpower guiding us through terrain, risking “lostness” and maybe allowing us to chance upon some astonishing new locale. Lostness itself is becoming lost.

But I’m riding my hobbyhorse there, when I know you meant interior, emotional lostness. Literature sometimes does validate that kind of free-floating. Hamlet, in his should-I-or-should-I-not overcomplexities, is lost inside himself. Of course (spoiler alert) things don’t turn out splendidly for him. Still, there’s something attractive in his thoughtfulness and maze-like cogitations; and the playwright who creates him also reminds us that in order to experience the marvels of Prospero’s island, you need to be lost to the tempest first—wrecked, even. Alice’s journey through Wonderland is a grand adventure, but she needs to be lost from the world, from the workaday world, to get there. So being lost can also mean being liberated from dailiness, from convention. In children’s literature, it’s often through something like a shipwreck—think Swiss Family Robinson—or through “a journey to the center of the Earth.” In the adult world, we sometimes just have to dig in our heels and close our eyes and ears. “Get lost,” merchants would annoyedly say to immigrant Jews seeking employment in the early twentieth century. Okay; and then some of them wound up creating Hollywood.

BUCKINGHAM

This goes back to the thing that I asked at the beginning, this unwillingness. I’m way too willing. For instance, there are all these hoops that you jump through that are not part of the art itself, like when you get your first book published and you’re asked to come up with lists of contacts and you’re spending like sixty hours on the computer setting up your own reading series. One question that went through my mind when I was thinking about this interview was, “How the hell does he do this?” That’s not, how do you do the tricks, but how is all of that in your head? It’s in your head because you don’t deal with the shit that you don’t have to deal with. You’re unwilling sometimes. I think that’s really admirable.

GOLDBARTH

Thanks, Polly. That unwillingness, let me warn everyone, doesn’t do much for sales figures and awards; so it’s heartening to hear someone value it. I’m guessing your students and your magazine staff live in a world predicated upon willingness. If your writing isn’t a small part of a larger project that includes grant proposals and reading series and tweeting and blogging and reading my tweeting and blogging, then you’re doing something wrong. But I would want to give you the opposite permission. Remember this moment. I’m giving you the opposite permission. It certainly won’t be bad for your writing. You should have the freedom to say, “Here’s my short story, here’s my sequence of poems. I just devoted the last six months to it. This is what I care to give to the world. Now, let’s go watch the World Series.” Some people, and these days many, do have an honest appetite for all of those extra-literary extensions of the creative act. If it’s an honest appetite to, let’s say, devote time and energy to marketing one’s work . . . well, fine. So be it. But that’s not who I am. I assume there are fewer people who read me now than might have read me twenty-five years ago. I’m not online. I’m not blogging. I’m not tweeting. Wichita isn’t Manhattan, NY. I’ve taken myself off the radar screen. (Plus, the whole ancient straight white male thing.) In a way, this doesn’t trouble me at all. That Robert Bly line: “I have spent my whole life doing what I love.” Why would I want to spend time doing things I love less at this point in my life?

BUCKINGHAM

In the interview you wrote for the Georgia Review, Walt Whitman asks you, “Do you think it’s easy to change?” I just finished reading Ovid, so Metamorphosis is in my head, change is in my head, that sense that everything is constantly changing, and yet there’s such a human resistance to it. It feels like we’re at a cataclysmic time in history; part of it has to do with technology and part of it has to do with COVID and part of it has to do with politics. How are you getting through it? And, also, I guess I’m looking for your helpline advice to help us get through the change. Pay by the minute.

GOLDBARTH

It will cost a lot per minute, for the “Covid-Ovid” answer.

I’m not, I don’t think, particularly mystical—although I love reading about flying saucer research and is there really a Nessie and can the dead actually call us up and leave messages on our clouds, stuff like that. But it does feel to many of my most intelligent friends, who are also not mystical, that something is happening now, a convergence of negative forces—COVID and TikTok and Trump Republicanism, QAnon, gun violence, Russian predation and trolling, race tragedy, the erosion of education, et cetera. The rise of terrorism, the death of the printed page, all of these things going on at once. In unfortunate ways, they reinforce one another. These things do seem to be in step, as if there is some power in this universe, some terrible negative zeitgeist at work that might boil out of the Earth in a foul black cloud like a CGI effect in a superhero movie.

Some change is for the good, though. You’re living in some overseas tyrannical regime and you’re being tracked by the authorities (as we all are, and certainly you are every second of your online lives) but there are also radical progressive groups keeping in contact with cell phones or constantly moving internet cafes, trying to fight against the tyranny, using that same technology that the despots do.

Online support groups provide positive enhancement for . . . well, you name it, animal shelters, abuse survivors, struggling bees and butterflies. I underwent three small surgeries last month, all easier and more efficient for being computer-driven robotic procedures. My parents survived World War II and the Depression, and I’ve made it through the Cold War, 1984, and the dreaded “millennium bug.” The foul black cloud may be there, but the sky is larger than any cloud.

As Ovid knows, it’s the nature of things to change. Uranium is always decaying; every second, its life is decaying out of itself into another life. That’s true for you and me, as well. Nothing’s going to be born unless something else dies, and its matter and energy recycle into the new thing that emerges. It’s the way the universe functions. The universe doesn't need us to function in the direction of change. Iron is always going to rust, whether we help it along or not.

Ideally, we can feel “at one” with that cycle. To the extent that (like anyone) I sometimes don’t feel that way, I can become Captain Unwilling: the universe is one of continual change, okay, but it doesn’t need my endorsement, my acquiescence. If I’m doing something, it is, not always but often, going to be to question the forward motion because that’s what some human beings need to be doing. The other stuff is going to happen no matter what. Let the universe take care of that on its own; I have postage stamps to buy.

I am only an occasional reader of poetry, but I love Albert Goldbarth! I am so happy that I came across this interview. I found it full of wisdom, as well as some useful tips for further reading. Please tell him that he made at least one person very happy. I will now dust off a few of his poems and reread them.