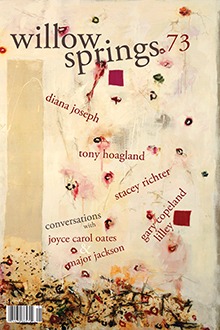

“Tobacco Road & A Proper Elegy for My Father” by Gary Copeland Lilley

A Proper Elegy for My Father

He is the black Marlboro man, the oldest son of a one-legged, gold tooth rounder. Abandoned homes down the road have fallen into ruin. Everything dies hard here, collapses into the kudzu pulling it down. This is the low-ground, the land of the maroons from the Great Dismal Swamp. Nothing lasts forever. The honeysuckle from the ditch bank and from the woods behind the house is in the air tonight, with the croaking of frogs and the waxing moon. A soft touch of Southern intoxication and I almost don’t want to light my cigarette, but I do. This is North Carolina, the tobacco state, even though most farmers nowadays are paid to not grow it. Here, traditions die hard. Out of the fog, plantation ghosts and Jim Crow walk tall, persistent as the oppressive kudzu, as old as the Dixie lost cause. We are born into this, and if we are lucky our fathers prepare us to live in it. Show us how to stand and throw down. Food for the table: they teach us to fish and hunt, to enjoy setting the hook, the recoil of the shotgun, the striking of the target. The rural cycle of life, everything dies hard here. Except my father: a scowl and a growl, a piney woods drawl, a drinkero f dirty water, a two-fisted church deacon, a logwood man, a long-haul truck driving Korean War veteran whose face was set so serene in his coffin that it was evident he’d died in his sleep. Unafraid as death approached, he’d said he was going to take a nap. His thick-fingered friends: a gathering of old crows weeping into their handkerchiefs at the wake. I say to myself, look at him, old black-man-cool in the blue suit that he will wear forever. Who doesn’t want to die like that, nothing coming down the road but eternal rest.

Tobacco Road

I.

I am fourteen, two years into my social isolation

after we moved from the grime and blacktop

basketball courts of my New York neighborhood

back to the piney woods and struggling farms of the North Carolina coastal plains.

I was the funny talking city boy that every local boy

wanted to fight, until they accepted the fact

that I would fight dirty. I would pick up anything,

and my favorite was a smooth fist-size rock. Nobody

wants to get cracked side the head with that.

I spent summer mornings bare-chested, shirt tied

round my waist, running through the woods

with my dog, and if they were ripe, eating wild grapes

golden in the daps of sun, the vines hanging

from some low branch of a tree; running through

the deer beds, scaring up rabbits, and avoiding

the occasional snake or bear. Every day

my voice changing, back and forth, from a soft lilt

to the scratch inhabiting any song I try to sing.

II.

Mr. Luther Grant

was coming through

the field between

our houses doing

his old pirate step.

His youngest brother

had chopped three toes

off his right foot

when he’d put it

on the block and dared

him to swing

the double-bladed axe.

I was peeling

potatoes on the porch

and when he saw

me he spit

the plug of tobacco

from his mouth

and the way

he set his jaw

indicated he had

something bad to say.

III.

Queenie killed five of Mr. Luther Grant’s chickens,

they say a dog that does that never stops.

She then laid herself among the dead birds,

surprised that they had stopped squawking, a game

of chase and catch where each chicken stopped

trying to fly away into the early afternoon heat.

She’d killed five in the treeless yard before she grew tired

of them and came back across the field, dropping

the last one halfway between the two houses.

I know Mr. Luther Grant had a right reason to be

upset; they say a dog that kills chickens never stops.

She was a city dog, my Uncle Willie’s dog,

which he’d placed in my care after he was drafted

and knew he was going to Vietnam. His one-

bedroom apartment had been Queenie’s home.

She slept at the foot of his bed and they went

on daily runs in the park. When Willie gave his dog to me

I’d begged my father not to put her on the chain.

One of the few times I’ve seen him agree to anything

that wasn’t his idea. And now, my dog Queenie

killed five of Luther Grant’s egg-laying chickens,

and they say a dog that does that won’t ever stop.

IV.

My father was drinking in the kitchen while

reading his Bible. He comes out, and greets

Luther Grant in the yard. They purposely

keep their eyes off me but are talking loud

enough to ensure that I can hear them. They are

formally polite. My mother washing dishes, watches

everything through the kitchen window and

looks her sorrow down on me and begins

a hymnal song, We‘llUnderstandItBetter

By and By. Queenie, on the porch panting

in the late afternoon corner of shade, is not allowed

in the house. My mother says all animals belong

outside. She dries her hands with the dish towel,

drapes the soft cloth on the kitchen sink.

V.

My mother steps out on the tilting porch,

Let me help you peel those taters.

We sit together on the glide and work silently.

A crow lights on the willow near the porch and calls.

Queenie perks her ears, waiting to see if it would

come to ground. I am glad that it does not.

Luther Grant stops talking, pulls out his chaw, and turns

to leave. My father promises to take care of it.

VI.

We are in the woods and the sun

is shining on the loblolly pines,

twilight, a hint in the near distance.

Not a cloud in the Carolina sky.

We pass a tree of wild golden grapes,

the vines hanging heavy off the low branches.

Flirting birds chatter at the abundance.

My father walks a quick-step ahead

while my dog trots beside me; he has

ordered me to come along, but I refuse

to carry the shovel or the loaded gun.

Absolutely awesome! Words are following and emotions are flying off the page! I could feel the thu Der in the boys heart as I read what was going to happen to queenie. Please share some more of your work. Don’t stop writing you have a gift!!