“Sunday Morning Coming Down” by Jessie van Eerden

WRITE THE WHOLE PAINTING and do not stop. Sunday is bitter cabbage and the glimpse of shapes down a brief hallway, involved and intent shapes. I am more cognizant of breath on Sunday-the way, as bodies lying on our sides like long-legged fetuses, we are aware of the heart thudding in the ear. On Sunday (a day welled up with the week past and the week to come, such that you experience all the days at once like a person set down, weary, before a painting) breath feels like the respiration of time, like God’s breath. I am losing my morning heat from the down-pocket of bed, enclosing myself in sweaters, but still I cool and require the space heater this day early in Lent. Sunday is breath and chill and stillness, the bitter salted cabbage as I help make the kraut, its tangy smell hazing the hallway.

The directive is to write the whole painting.

My boyfriend R recently gave a point of view lecture on whole-painting writing: Give the story all at once as if you’re trying to confront someone with an acrylic on the wall-can someone receive a story on all levels, not in narrative sequence, not in sequestered moments of time, not from one point of view but a roving one? During the lecture a student in the front row yessed like a Baptist who has read the Scripture the night before and so already knows the parable, yes, how the kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed that grows into the largest tree in the garden, with all the loud birds roosting there as they might roost in the tree in his chest, so, yes, he said while each downbeat syllable of parable fell from the preacher’s mouth, which was the lecturer’s mouth, R’s mouth, reading excerpts from Lawrence Durrell and Kay Boyle and William Goyen that traversed time and perspective in shock-color layers. Try to write the whole painting, R said, even though we can’t ever write the painting, for all we have is language, but, yes, the student already knew the struggle that each writer in the room knew, the impossibility, and the insistence that we go forward, marching, toward failure, amen and amen.

The directive made me want to write about Sunday.

Perhaps it’s because, as a child, Sunday was the day I felt an intersection of currents and a simultaneity of layers, I felt the eternal within time, a press of eternity’s hand, because of the habit of church where all forms and patterns and braiding-back of my hair were intended as poor representations of realities timeless and glorious. The Sunday moment is sharp and prismatic in my mind: stepping a penny loafer down from the Dodge to the gravel, decked out in my mother-made plum jumper with flowers on it, with wooden buttons I’d picked out myself at Jo-Ann Fabrics, in the store-bought lavender shirt underneath and a jean jacket over top, a cheap silver locket secreted against my chest bone. And of all Sundays, it is Easter Sunday-so there is the sleepy shock of the Sunrise Service beginning in the dark, and somebody’s lilacs slouch wetly and everyone’s daffodils have either nodded or upturned their faces to the sting of frost and the soak of its melting to follow. Maybe that childhood storehouse of Easter Sunday strikes brightly now, like red and yellow acrylic, because of today’s cold Lenten air, though I don’t know that a Sunday in Lent is any different from one in Ordinary Time. It seems, in our cyclical week, Sunday is a measure, a ritual of reckoning, an end, a beginning, full-bodied and populated. Things come to bear on Sunday, things you have borne, how things will bear out. All is with you, all you have loved, hated, vowed to never leave and yet left.

I HATE SUNDAYS, I TELL R. I dread Sundays.

SUNDAY SEATS YOU CLOSE TO A PORTAL. It’s very like stomping the cabbage each year for the kraut. A child is engaged in a chore that pins her to the kitchen bench facing the brief hallway of motion and sound. Time moves more slowly here, or more quickly, or both. She turns to see her mother come through that front screen door portal with even more cut cabbages mounding in the granite washbasin propped on her hip, cabbages sliced from the stalks, from among the big blanket-furled leaves. The mother cuts out each core then shreds the cabbages, for a few years, with the manual kraut-cutter that looks like a washboard only with blades, like an oversized cheese grater, then, in time, with the electric food processor in batches, then she dumps it all into the crock on the floor between the benched girl’s knees. The mother salts a layer, dumps another-salt, sift, dump, salt.

I DON’T THINK IT’S LOGICAL, R says, not unkindly-it’s just a day like any other. (And it’s true that I am sometimes quite illogically unmade on Sunday, in tears and wadded up with my dog on the couch. This is baffling.)

I say, But the past is always with us, like Faulkner said, you always quote Faulkner, it’s like that, the days are always with us, and on Sunday somehow you can feel the days well up.

Dreading two back-to-back, seventy-five minute gen-ed classes is logical, he says, which is why he dreads Tuesdays and Thursdays.

But he wrote to me once: Life of course is the whole story at once and our frustrations with it are the tiny boxes we try to force it into. In both writing and life we have weak artificial mediums to work with, words and time. So he does understand.

Should we have a baby? I say.

What?

I’m nearly thirty-seven, I remind him-my window of time is circumscribed, biological clock and so forth.

So that’s what this is about. Logically, yes.

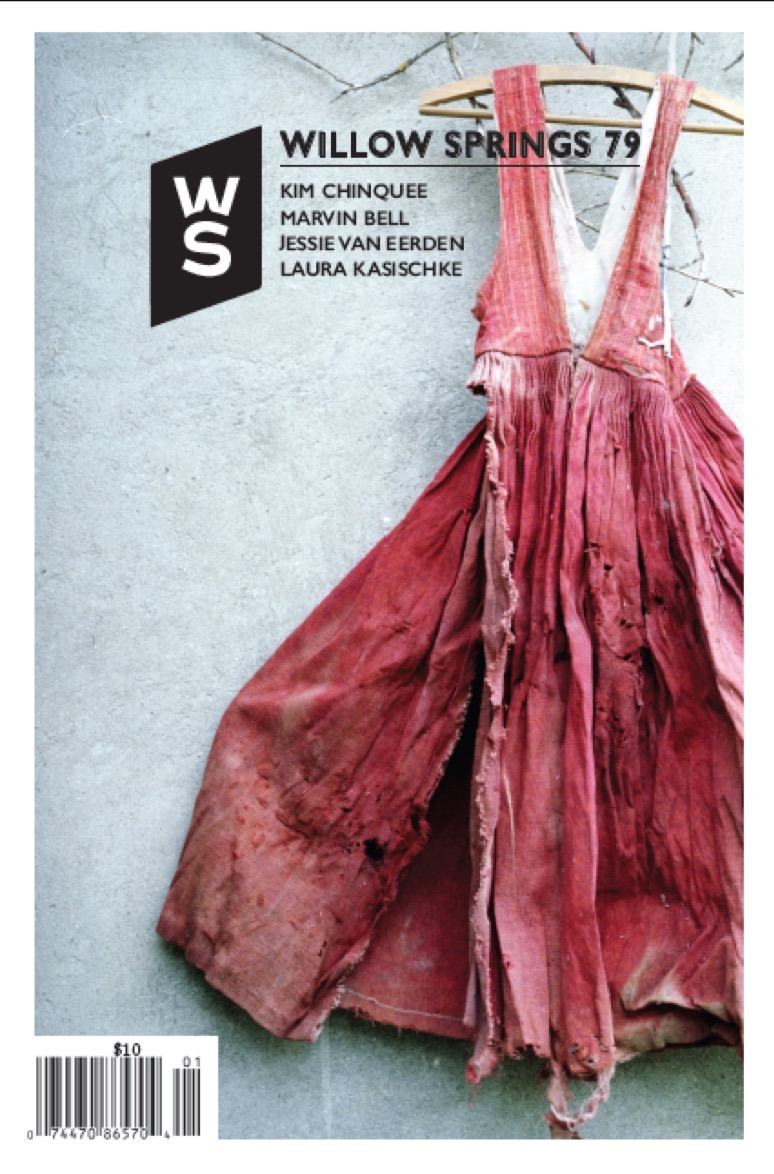

R READ EVERYTHING William Goyen wrote, read the newly re leased biography and included in his lecture how Goyen didn’t write for self-expression but for the communal voice, in multiple frames, multiply nested tales, his words and paragraphs stick figures-black letters upon white pages-but flesh hangs from them like jellyfish skin, translucent sheets billowing, flesh and dress ballooning into color and light. Goyen’s stories are festooned with other stories, or infested-it’s like traveling down someone’s throat lined with rubies. This is the Goyen who wrote inside a parenthetical in House of Breath-a book in which sentences sometimes don’t stop for pages, or maybe never stop-who knows the unseen frescoes on the private walls of the skull? l don’t know who knows, but he tried to write them, to catch the brightest color right when the fresco went up on the lime plaster, before it could dry.

IT’S TRUE THE BABY QUESTION troubles me with a louder clang of longing on Sundays. A baby’s tiny skull and heat and light and hair, do I want to try? Lots of women turning thirty-seven this year are fearing they will regret not having children, but is fear reason enough to have them? My friend K writes in a letter, Is the pang of knowing you will not know the profundity of that kind of love any reason to have a baby? Out of desire for profundity? K is a friend to whom I often write on Sundays, the practice of a Sunday letter being one of my coping strategies.

Ought I to have a baby, as though it were completely up to me and a matter of my will, like donating to Mothers Against Drunk Driving when they call? And why do we say “window of time?” It makes me think of Madeleine L’Engle’s young adult fantasy A Wrinkle in Time, her lovely powerful Charles Wallace, the little boy ready to travel through time. I remember the word tesseract and my brother’s science project on black holes, the model he built from a coffee can and a Yahtzee box, aimed just so at the mirror hanging on our parents’ wardrobe that held things like our handwritten immunization records and Murphy’s Mart bags full of material scraps for quilts Mom would make over the next forty years, preferring to sew them by hand. I suppose we say “window of time” because of the frame of limitation. But what if it’s another part of the metaphor’s vehicle bearing forth a different tenor; what if it’s because of the window glass to see through, to be seen through, like a portal? Like a passage? Like a hallway of time: What I am talking about is being a memory for a child who looks into the passage of time, the memory making an imprint. Back to that same screen door, for instance, portal from indoor to outdoor, the girl child-me watching her mother who has boiled water for ear corn, now that kraut-making is done, removing the corn then carrying the pot through the screen door that closes with its soft slap upon its spring, and tossing the silk-littered water off the side of the porch instead of in the sink, and standing a few beats after, listening to the supper hour shift and adjust. The image of it through the screen mesh in the greening light will be forever recycled in the girl’s mind by dream by dozing by grief by time.

So who will see and know me in that way? That is the question to catch in my throat. I am creating no tableaux of oddity and ritual upon a porch floor to wake in the mind of a child after me-I will disappear. I will have to be okay with disappearing. Or try to be recalled another way, and this is maybe why I’m writing a novel in which a woman remembers her mother just so, with the pot in her hands emptied of all but a few corn silks, so still. And if l can write in a way that comes up off the page in translucent sheets of flesh and color, billowing from the letter-bones, like absurd and wondrous jellyfish, like a slow ornate pop-up book, or full-face like a painting, all in acrylic of searing brightness-then maybe that is enough. Maybe that is how to spend my window of time.

I wonder, do I sit on a cold Lenten Sunday to simply write against my own disappearing?

TO THE AVERAGE AMERICAN MALE, R says, Sunday means one thing.

Sex.

No. Professional sports.

Right, I say. R may not understand the dread of Sunday, but my friend A understands. Another fucking Sunday, she says, AFS, we coin, Happy AFS! Here is a Ziploc of cookies to get you through AFS, I had AFS on Monday this week-so go our texts and emails in between the classes we teach. PMS on AFS, double whammy. She gets the Sunday New York Times delivered and reads it all as palliative. And my friend SB understands, she’s in favor of our new acronym, she’s Pentecostal after all, she understands the kit of things needed for AFS survival. Sometimes she goes sailing.

At its most basic, it’s the smeary weight of a sinner’s penance, or, with the weekend almost over, it’s Monday creeping close with its job-gloom. It’s the knowledge that Friday’s buried memory of failures will be Monday’s pert reality, or it’s the nostalgic chime of a church bell calling because you once wavered hot like a mirage with the rest of the faithful through the hymns and it ‘s been awhile. It’s the memory of family time, all the Sunday dinners, and now your siblings flung far across the world calling home on Sunday, if there’s time. It’s concomitance of vague emotions, sentiments layered together like filo dough.

At its utmost basic, it’s the terror of one’s annihilation.

JOHNNY CASH UNDERSTOOD, as he understood everything. I sometimes YouTube his hangover song, his cover of Kris Kristofferson’s “Sunday Morning Coming Down.” In the song, the speaker is on the “Sunday morning sidewalk” wishing he was stoned: “‘Cause there’s something in a Sunday/That makes a body feel alone,” as alone as the dying almost, Sunday morning coming down like a fog, a curtain, a crumbling ceiling, an axe.

I LOVE “SUNDAY MORNING, 1950,” a poem by Irene McKinney, the way I can slip into the background in my plum jumper from the 1980s:

In the clean sun before the doors,

the flounces and flowered prints,

the naked hands. We bring

what we can-some coins,

our faces.

I LOVE ROBERT HAYDEN’S POEM “Those Winter Sundays,” which I have taught in several classes and which falls flat against the students’ ears each time:

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather

made banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

Sundays too, in class always emphasizing that tiny adverb that’s so heavy, for there was no reprieve for him from the cold that cracked his skin. Fires must be built on Sunday morning too, ashes must be shaken down; it is a day that is no different from any other but it was the day on which he noticed the lack of gratitude. It was the day he was lonely. And the day his son remarked, memorialized, as having a palpable difference.

SUNDAY IS THE KRAUT-STOMPING because when you’re stomping the salted shredded cabbage with a thick cherry branch, shaved and sanded smooth, you watch the patterns in the linoleum and wait. You have a sense that it will be the others’ turn soon, later, long later it seems, because, as you lift your head, they-two brothers and a sister-blur through the short hallway to the bedrooms and bathroom and back out. The space swells with their bodies. They pass by to move through the screen door portal, out to the porch floor, then to circle the house on bikes on the path grooved and grassless. Time swells with their movement and faces and teeth come in crooked and hair curly like the Brillo pad your mom will use to make the floorboards shine, the whole floor, on hands and knees, once all her kids have left, still scrubbing at the years of drifting-down skin cells and dirt. Now you smell the clean foam of the bitter cabbage and foresee the banded linen towel or old pillow slip that will shroud the crock for six months in the basement corner. Six months of waiting under a thick layer of mold and souring, almost rotting.

Stomp-stomp with the sanded stout branch, preparing the salted cabbage for waiting. Waiting too for your life to start, to join the blur of motion. Plunging the kraut stomper between your knees down into the crock untapered, the sound of the screen door slapping shut. There is dread in the waiting, for you feel you will run out of time.

l’M NOT SURE YOU WANT TO HAVE A BABY. He tries to say this not unkindly.

Maybe desire and dread are the same thing.

IT HELPS SOMETIMES to write letters on Sunday. It’ s a hopeful stutter of voice sounded before working on the novel. Today I answer my friend J’s six dense pages of lovely longhand, all her news about the new rooster-He is all colors a rooster can be and looks hand painted-and about Iris the feral cat, and Beloved the horse not yet trained well enough to ride, and J’s own blurring eyesight.

Then novel work because part of my survival plan is to write on Sundays all the way through until noon. This time is demarcated on my weekly schedule color-coded with Prismacolor pencils from my childhood desk cubby, pencils that once shaded the eyes of a lamb on a newsprint Easter kite. Why noon, as though something magic shifted at noon? Because it indicates a fully committed morning, to give it everything, everything you remember and half remember and inexplicably love. Beside me hangs a painting-Georgia O’Keeffe’s Cow’s Skull with Calico Roses-a canvas replica I ordered online. I wanted to see the longhorn skull better because the section in the novel in which the character has a conversation with a cow skull was growing more and more confusing. I wanted to see the whole skull before me and I felt it important to get the one she painted with fake flowers as garland, and I felt it important that the skull look like a womb, and some of her longhorn skulls look shredded down to ward the nostrils, like pulverized cabbage. Why, I’m wondering, does my novel’s main character miscarry, and why does another character throw her babies away? Why the thwarted womb like a portal, all banded in suffocating gauze? Why not write a mother? I don’t know why. I’m writing in half dream, that is all a novel really is.

I LOVE ABRAHAM HESCHEL’S 1951 BOOK The Sabbath. In Judaism, the Sabbath is Saturday and not Sunday morning like it is for the Baptists and Methodists, parking trucks at a slant in ditches beside overfull gravel lots, but the principle of the day of rest, the set-apart holy day, is the same. I remember dressing for Sunday service once and asking my mother, Why do we dress up for Sunday? Because it should be a different day, she said.

Heschel writes about the Sabbath as though it were something we go out to the porch to see in all its loveliness. It’s a day released from labor, but its spirit is a reality we meet rather than an empty span of time which we choose to set aside for comfort or recuperation. It’s a day on which we are called upon to share in what is eternal in time. It’s a palace in time which we build. Time’s passage again taking spatial dimension: a stone passageway of ornate carvings and tile work as part of a palace. In the atmosphere of such a palace, Heschel writes, a discipline is a reminder of adjacency to eternity. It’s discipline and abstentions are what it’s known for-and so is the traditional Christian’s Sunday Sabbath, never stopping at the grocery store to spend money after worship, never cranking up the Weed Eater. Reading Heschel on my Sunday Sabbath, an icy Sunday during Lent-the very season of abstentions-I feel a strong desire to run out to Go-Mart to buy some peanut M&M’s, just to slip out from under the weight of all that beautiful principle. But I keep reading about Sabbath as a presence, felt and arresting and palatial.

It’s calming.

ON SUNDAY I FEEL the unbearable welling-up of time and see what the kraut-making girl sees: her mother and sister and brothers in a blur of color as she stomp-stomps the crock floor and the abrasion of the tough leaves makes them give way to juices that foam up rabid. What I see from the kitchen bench is my mother’s longing, my siblings’ movement out into the world, as if the image of that hallway off the kitchen is a breach of time, an image conjured on a day, Sunday, which is a day when time being culled out from eternity is understood as illusion. On Sunday maybe we see for a moment how God sees, without illusion. Maybe we try on the timeless gaze of God and try to breathe and bear it. What a dreadful, awful gift, to lose time’s blinders.

There is the story in the Book of Genesis about Hagar, Abram and Sarai’s servant turned concubine, turned surrogate. Pregnant with Abram’s child, she flees the barren Sarai’s jealousy and cruelty. Out to the wilderness Hagar goes, loosed and flapping in the wind, pregnant with the shifting blood of her boy Ishmael who will be cursed into terror like a wild donkey. She slumps by a spring seeping up from the dust. She is weary, but she is visited, and she calls the spring Beer-lahai–roi, Well of the Living One Who Sees Me. I have seen the one who sees me, she says, as though she suddenly understands what it means to be seen by such a gaze as God’s. Hagar becomes one of the few to understand what God’s gaze takes in: fetus unfurling, woman with a tooth aching at the root, for it’s loosening, hair falling out, pelvic bones reconfiguring in the third trimester from marrow to foam rubber, and also her last gasp, burial, and lilacs on her grave. The whole painting, all layers at once, every window of time.

It is not really imaginable, that kind of gaze. Even on a reflective, moody day like Sunday, we can feel only the overwhelming layers of our own lives. The past is with us (said R to me, said Faulkner, said the experience of divorce, said the body returned home and sleeping in the childhood bed-I remember when it was the four of us, a heap of breathing, anxious and fertile and unstoppered breath, and how our mother’s voice now echoes, just once more, can it be that way, as she runs clothes through the wringer and the house thickens up with voicelessness, and she scrubs the floor boards to luminous glow with a Brillo pad to be in close proximity to the paths traveled upon them through time). Even just our own lives are unimaginable-think of all the others: maybe what the girl making kraut sees in the brief hallway is the blur of motion of the others, not only brother and sister but all the others, the eternal within time, the story nested in story, and the attempt she would one day make to write it down, the whole of it.

I DO NOT KNOW ABOUT A BABY. Sometimes the confused longing gets to be too much.

Sometimes it’s just about wanting what we don’t have, R says, and this helps.

I picture my heart opening-how wide it can open if l let it. That wideness is what gratitude is, and I think, on this cold Sunday, that practice of a Sabbath is a fight for gratitude in the midst of quiet panic, in the face of your window closing or going dark. And gratitude is the stuff of eternity since it trains our eyes on time’s abundance instead of on the illusion of time’s scarcity. It’s as if gratitude creates time, lays it the way a hen lays eggs, little minute-chicks wide mouthed when hatched in the nest, and they trill and cry, try to add sound to the painting, for it should have sound too. Heschel writes about running to the Sabbath with sprigs of myrtle, as if to a bride. Wear your most beautiful robes, sing your most beautiful songs, bring your most beautiful acrylics.

Who knows whether it’s true that, in the end, all we have are these minutes and hours to measure our lives, that all we have are these poor marks to work with, black symbols on white pages? It could be that we have everything.