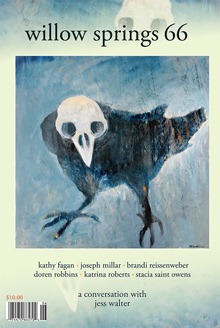

About Stacia Saint Owens

Stacia Saint Owens grew up in Kansas and is a graduate of Brown University’s MFA program in Creative Writing. She also holds a BFA in Theatre from Southern Methodist University. Her fiction has appeared in Southern California Review, Wisconsin Review, Willow Springs, Dos Passos Review, Smoke Signals, NIGHT, Confrontation, Quarterly West, and The Massachusetts Review. Her work was selected for Special Mention in the 2010 Pushcart Prize Anthology. Her short story collection, Auto-Erotica (Livingston Press 2009), was the winner of the Tartt First Fiction Award and was shortlisted for The Saroyan International Prize in Writing. She is a former Lecturer in English Literature at Harrow College in London, and now resides in Los Angeles, where she is writing a novel.

A Profile of the Author

Notes on “Color by Number”

My grandfather was a police detective in St. Louis, and I’ve inherited an interest in true crime. The family lore handed down from my grandfather’s career includes:

His very first day on the force, as a minimally-trained beat cop, when he set off walking and two blocks from the station was immediately accosted by “a raving lunatic running up and down the fence, naked as a jaybird,” an escapee from a psychiatric hospital.

Arriving at a domestic violence scene to discover that a man had beaten his wife, children, then himself to death with a ball peen hammer.

Bursting into “Negro pubs,” lining the patrons against the wall, and stealing money from their pockets, which he did reluctantly but could not figure a way out of as this practice was ordered by his superiors (who also collected the money), and he had a wife, seven kids, and two parents to support. To cope with his guilt over this and other institutionalized abuses, he began drinking at work and succumbed to alcoholism.

Part of my father’s driving ambition was the desire to keep his family safe. He shielded us from any urban exposure, raising us in the squeaky-clean suburbs of Kansas City and later in a nearby small town dominated by the law-and-order industries of a prison system and an Army fort. There was a blatant incongruity present in my father’s level of hyper-vigilance, the scare-tactic true stories he told us, and the sedate, congenial environment we lived in. This juxtaposition gave me a strong sense of subtext from an early age, an awareness that although I could not see it, very bad things were happening at this very minute.

As a teacher working with at-risk high schoolers and female prisoners, I found myself swimming with sharks, and it was crucial to learn to recognize and safely interact with people manifesting various psychological disorders. These experiences incited a lot of questions about nature vs. nurture, neurobiology, self-determination, and personal vs. societal responsibility.

I have always found appealing the phrase “an accident of birth,” the way it encompasses both luck and misfortune, its inarguable reminder that our very existence is ultimately due to a highly random meeting of a specific sperm with a specific egg. We are fiercely protective of our individuality, but it all could have so easily gone another way. Many different versions of ourselves were almost born. Many different versions of ourselves are continually shaped or eliminated or resurrected as we stride, struggle, or stroll through life experiences.

American culture encourages individuality and aspiration. There is a fine line between these qualities and self-absorbed ruthlessness. The latter is often considered acceptable, but can cause as much damage as the more-feared anti-social disorders. What is the difference between a corrupt police officer who is driven to drink and the one who steels himself and accepts that he must do what he can to survive? Which one of these two can be classified as sick? They are in an identical situation, so do they have exactly the same choice?

“Color by Numbers” is an exploration of these types of questions. The two main characters’ lives progress in rough parallel as they grow up in similar but crucially-different circumstances and eventually become responsible for their own choices. One is an outwardly-conventional, law-abiding person; the other is an outwardly-charming sociopath. They are both tormented by lack of connection, which may be due to their upbringings, heredities, personalities, levels of intelligence, or mere accident. The omniscient, measured voice is reflective of the clinical tone of an official report, and does not allow either character a narrative advantage. The characters are afflicted with frenetic, messy compulsions that they struggle to contain, just as the rigid, repetitive format of a police, medical, or science lab report attempts to coolly eviscerate emotion while describing events that normally provoke an impassioned telling. The structure is meant to shift the role of authority from author to reader. The reader is the one for whom all available information has been compiled, who will be expected to render the final diagnosis or judgment.

The numbered sections are episodes, in the dramatic sense of self-contained events in a series and in the medical sense of recurrent pathological condition (such as “psychotic episode”). In the original Greek, “episode” meant a digression between two songs in a tragedy, and I like the idea of seemingly-extraneous events causing significant repercussions. A numbered list always suggests authority and finality to me, along with an escalating inevitability. Yet I am simultaneously aware that a list could be created at any length, and that every list is excluding other items. This duality makes it more challenging for the reader to judge the characters—and such judgments should be difficult, made with thoughtful skepticism and humility.

The structure also evokes a color-by-numbers activity, which is creative, but prescriptive and limiting. There is little penalty for disobeying the color-by-numbers rules and choosing our own color combinations–even coloring outside the lines—; however, most of us are conditioned from an early age to honor the parameters of the game. Does this create the best picture? Once again, how much choice do we have?

The columns suggest lives unspooling on separate tracks, also the creeping, stalking energy of something sinister gaining momentum. The paragraphs that end each episode are attempts to draw conclusions, and do so imperfectly. The paragraphs do draw connections, pointing out that although the characters feel oppressed by isolation, they are actually all entwined and all impact each other, though they do not perceive this.

Notes on Reading

I am drawn to fiction that takes risks and meddles with language while remaining fundamentally accessible—which does not mean transparently knowable. I grew up in a household that valued literature, but the wider community was not especially literary, and I think that is an accurate description of almost anyplace in present-day America. How does a writer captivate and entertain while challenging both intellect and emotions? How can a work be innovatively provocative and enduringly universal? I admire writers who strive to construct these bridges, who sincerely and zealously invite the reader to get involved with the work. Check out the riveting historical re-imaginings of Edmund White, the muscular fabulism of Anna Joy Springer, and the elegant intoxicants of Carole Maso.

I read widely in other genres. This limbers my brain, loosens my self-imposed constraints, and builds my trust in the readers’ adventurousness. Poetry always knocks me into an enjoyable jumble, as do stage and screenplays, which have a more immediate mission to please the audience. I recommend the poets Sawako Nakayasu and Paul Foster Johnson; the playwrights Sarah Ruhl, Laura Zam, and Christine Evans; and the experimental public games of Rob Ray (www.robray.net/virtualart), a delightfully vital and forward-looking kind of “reading.” And if a million people have read it, I’m interested. I am fascinated by discovering what motivates people to read. So: magazines, horror novels, viral web pages, pop song lyrics, lasting classics. The plays of Agatha Christie are lovely little gems, compact and consumable and unsettlingly macabre all at once. Deceptively complex, like even the most ordinary day of your life on this lush, volatile planet.