About Jill Christman

Jill Christman’s memoir, Darkroom: A Family Exposure, won the AWP Award Series in Creative Nonfiction, was first published by the University of Georgia Press in 2002, and will be reissued in paperback in Fall 2011. Recent essays appearing in River Teeth and Harpur Palate have been honored by Pushcart nominations, and her writing has been published in Barrelhouse, Brevity, Descant, Literary Mama, Mississippi Review, Wondertime, and many other journals, magazines, and anthologies. She teaches creative nonfiction in Ashland University’s low-residency MFA program and at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, where she lives with her husband, writer Mark Neely, and their two children. Since the time surrounding the writing of “Bird Girls,” she has been working on her next book, a memoir entitled Blue Baby Blue, and she’s really hoping to finish it before 2012. Just in case.

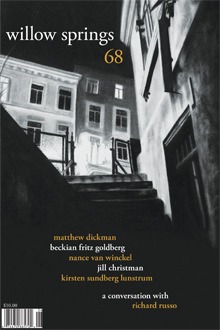

A Profile of the Author

Notes on “Bird Girls”

The slumbering baby in the first paragraph of “Bird Girls” is our first child. Ella just finished first grade yesterday, so I have evidence in her they-grow-up-so-fast body to date the origins of this essay six years ago. At the time, we’d been in Indiana for a little over a year, and as a northwestern mountain girl adjusting to life in the Midwest in all its permutations of flatness, the present-tense moment that kicks off that essay was jolting to me in a reassuring way. Those trilling, chattering, whistling birds were so loud, so simultaneously cacophonous and differentiated, so sexual (after all, that’s precisely what the little buggers were getting up to in the pink dawn), I was indeed transported right there in my Indiana bed back to those Oregon woods. True story.

Because my body was curled around a sleeping baby, I couldn’t exactly move, and the combination between that circumstance and the sharp, Proustian memory of the collegiate birding trip collided to send me into an exploration of shifting female identity over the course of a long and mobile life: Who am I? Who was I? What is the relationship between the young woman on the mountain and the older one in the big bed?

In those early days of motherhood I was often stuck under a nursing child with my hands too wrapped up in petting and holding and feeding to be much use on a keyboard. I did a lot of writing in my head and then hoped for a moment to prop the baby between me and a laptop and get some of it down. That morning I got lucky. Six long years later, I figured out what the essay was really trying to be about and finished it.

Notes on Reading

As an essayist, memoirist, and teacher, I’ve been obsessing about the handling of time in nonfiction (for a great book on this subject, check out Sven Birkerts’s The Art of Time in Memoir), and I’m beginning to think that all our best questions come from folding time. I had a fabulous teacher/mentor in my graduate program at Alabama, Sandy Huss, who scribbled a note in the margin of one of my short stories way back when: Before the manuscript there is silence. The manuscript breaks the silence. Why here? Why now? These are important questions for nonfiction writers, too. Does the now-narrator have something she must ask the then-self? Can the reader be convinced that this excavation of the past and memory is real and necessary? My students are sometimes shocked when I tell them I never write anything when I know what I’m talking about, when I know the answer. Why bother? The work then has already been done and the inquiry is false. Give me the good, unanswerable questions any day.

The fundamental book for lessons in the essential shaping of life material, the artful folding of the magic carpet, of course, is Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak Memory. I return to that book—and Nathalie Sarraute’s Childhood—every year. I thought about Nabokov this semester when I read two books that were new to me: Kathleen Finneran’s astounding memoir The Tender Land: A Family Love Story (the first chapter could be a textbook for folding time) and Eula Biss’s provocative collection of essays, Notes from No Man’s Land (Biss’s juxtaposition of her own present-day navigation of her neighborhood with our national history makes an open-eyed look at race possible). Speaking of Biss, I’m also drawn to nonfiction that teaches me new things about the world, which is why I’m a steadfast Lauren Slater fan, and why this year’s nightstand books included Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks and Annie Paul’s Origins: How the Nine Months Before Birth Shape the Rest of Our Lives.

Also, my husband got me a Kindle in a red leather case for Christmas, and because our house is stuffed to the rafters with books with which no one can part—and because the red leather is so snappy—I’m trying to choose books I can bear to enjoy in e-reader form: Skloot’s Immortal Life was my first, and because my colleague Sean Lovelace says it should be, Richard Brautigan’s Trout Fishing in America is on my summer list.