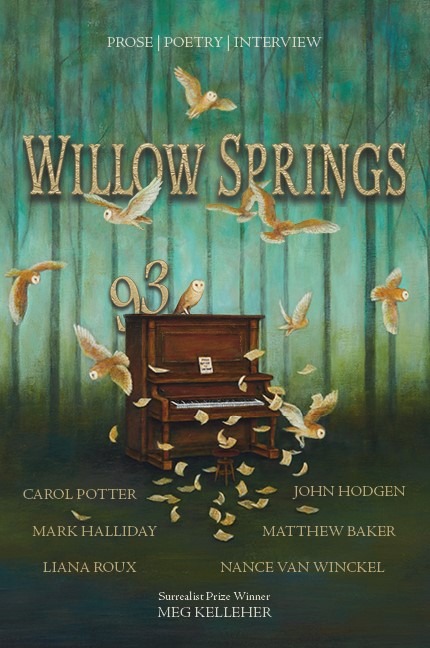

Found in Willow Springs 93

JULY 7, 2023

POLLY BUCKINGHAM, KURTIS ELBING, ORAN BORDWELL, ELIZABETH GRAVES & KEELY LEIM

A TALK WITH NANCE VAN WINCKEL

Found in Willow Springs 93

EMBRACING IMAGE AND PERSONA, surreality and realism, form and disparate form, Nance Van Winckel’s poetry, fiction, memoir, collage, photomontage, and everything in between is as engaging an experience on the page as it is moving emotionally and intellectually. Throughout her work, Van Winckel contends with the personal, cultural, and political histories that shape people and the environments they occupy, the nature of memory and grief, and the nuances of familial relationships. As Herman Asarnow writes of Wan Winckel’s No Starling for The Cincinnati Review, her poems “sure-handedly carry out a thoughtful examination of mortality, of the pioneering spirit, of injustices caused by nature and by humanity, and of a sense of having to live this life in our own laughably frail and painfully desiring bodies.”

Nance Van Winckel has published seventeen books of poetry, fiction, and hybrid works including The Many Beds of Martha Washington (2021), chosen for the Pacific Northwest Poetry Series; Our Foreigner (2017), winner of the Pacific Coast Poetry Series; Book of No Ledge (2016); Pacific Walkers (2014), a finalist for the Washington State Book Award; Ever Yrs (2014); Boneland (2013), recipient of a Christopher Isherwood Fiction Fellowship; No Starling (2007); and her first full collection of poetry, Bad Girl, with Hawk (1987). Van Winckel has also been the recipient of two National Endowment for the Arts Poetry Fellowships, three Pushcart Prizes, and awards from both Poetry Magazine and the Poetry Society of America. She is currently teaching in the MFA in creative writing at Eastern Washington University, and once served as the editor of Willow Springs magazine.

Nance Van Winckel kindly invited us to her home in Spokane where we gathered on the back porch, overlooking the Spokane River, on July 7th, 2023. We discussed the roles of imagery, persona, intuition, and politics in poetry, and the benefits of joys and writing across genres and forms.

KURTIS EBELING

There are moments in you work in which arresting images seem to emerge from extreme emotion or felling. “They Flee From Me” in Pacific Walkers comes to mind. I’m also curious about your thoughts on the role of imagery in poetry generally. And, particularly, what are your feelings about the relationship between imagery and the expression of feeling on the page?

NANCE VAN WINCKEL

There’s something the image can create for the reader: an entrance into enchantment. As a reader, I like to be drawn into a place where I’m completely thrown out of my life, lost in language and tone, the mind behind the material. I don’t think so much when I’m tooling the image about the emotional resonance—that’s going to be a test that comes later. I’m focused on exploring image and putting images next to each other in different ways that maybe charge them in unexpected ways. I’ve gotten so interested in putting images together that now that I’m doing it physically with collage and photomontage and all sorts of visual methods because they all do that same thing for me when I’m making them, that sense of enchantment.

POLLY BUCKINGHAM

I love that term tooling the image. That’s great. What are some of the techniques of tooling the image?

VAN WINCKEL

The poet Charles Wright cam to visit a college where I was teaching, so I was driving him back and forth to the airport, and, oh my god, the poor man, I was pumping him the whole way there, the whole way back, with my little questions. One of the things he does, he told me, is “commit a stanza or two of a draft—a poem that’s in process—to memory, and then when he’s driving around doing errands, he starts to move the stanzas around. And then he starts to move the lines in the stanzas around. And then to move the words in the lines around.” He said, “I turn it over to my ear.” That’s the kind of tooling I’m most interested in. I wrote an essay about Wright’s work, and a phrase I wrote about him that stays with me because I have to think about it for myself a lot, too, is, “the hand of the image in the glove of sound.”

BUCKINGHAM

That’s beautiful. I know you’re a fan of surrealist poetry. Can you talk about its influence on your work and what you love about it?

VAN WINCKEL

Right. I do, I like a lot of the surrealists. I feel like I’m a hodgepodge of influences. One of the things that was helpful to me about reading some of the surrealist poets was how little narrative scaffolding the poems need and how much they really depend on what we were talking about, that juxtaposition of imagery, depending on the reader to make other kinds of connections besides narrative connections. Narrative seems less an expectation for the reader with the surrealists, ,so good. Instead we get a sort of sense of what the locus of the poem may be.

ORAN BORDWELL

Even in their titles, like Bad Girl, with Hawk and The Dirt, there’s this consistent recognition of the earth and of natural imagery accompanying, though seldom overshadowing, humanity and the human experience. I’m curious about how you might describe your relationship with nature, what role it plays in your writing process and the work itself.

VAN WINCKEL

I’m not that picky about what aspects of the natural world appear in my poems, but I do feel like the poems need to be IN a world. As Dick Hugo says, “You can’t go nowhere if you ain’t nowhere.” I don’t think of myself as a nature poet by any stretch, but I do like to know where I am. It’s hard to draw people without drawing the space around them, too.

I was a journalist before I went to grad school to study poetry, and what we learn in journalism is the who, what, when, where, how, and why. I still think about those issues in writing a poem. Where we are: reminding us of the physicality that we’re in; what’s going on, give us some action. I can’t stand poetry that doesn’t have something going on in it. I don’t care what, but I need action, baby. And then, who. Who’s the consciousness? That’s all about tonality. Personality equals tonality. Getting a good interplay of those aspects can really energize a poem.

Also it’s hard to draw people in poems, or any writing really, without drawing the space around them, too. When I was working on Limited Lifetime Warranty and Boneland, we drove out to freaking North Dakota and Montana. My husband and I went on a dinosaur dig, so I could convey an accurate physical description. People need to sense—okay, yeah, this is a real place. I’ve lately been liking urban poetry, cityscapes—have you read Alex Dimitrov? His poems are all set in New York City, and they’re just full of bustling and cab rides. Oh, and Singer’s Today in the Taxi. Every poem starts, “Today in the Taxi.” He was a cab driver for years in New York, and you get the sights and sounds of the physical world.

BUCKINGHAM

We were talking a bit about persona in your work. About Pacific Walkers and the persona being the journalist and to what extent that persona is fictionalized. How important is the notion of persona to work?

VAN WINCKEL

That’s what made the whole book come together—finding that tonal way into it. In that job I had, they sent me out to do a story on all these bodies they would find in the spring around Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Mostly they were homeless people who had died, had too much of something, passed out, and froze. And when the coroner got called out to pick up the bodies, the newspaper would send me, too. It was really hard.

BUCKINGHAM

So you actually saw the bodies.

VAN WINCKEL

I did. I saw them being put in the plastic bags. And it stayed with me, but I moved it to Spokane in the book because I could access the Spokane Coroner’s website, where there is detailed information and because this place was fresher in my mind and that gave me a little bit of distance from “factuality.”

BUCKINGHAM

In Ever Yrs, there’s the persona of Nance with the letter at the beginning that’s to you. It seems like it’s a real letter, and then you get reading, and it’s like, oh, this isn’t a real letter. That’s playing with persona, too.

VAN WINCKEL

That was super fun to do. I loved working on that book so much. Finding the voice of that grandmother, I really loved her. I miss her sometimes. I wish she’d come back and talk to me again.

BORDWELL

I noticed a focus on children and their perspectives, as well as on animals, in some of your books. Often, they’re abused, neglected, lost, injured, or otherwise oppressed, though some are ultimately adopted. How and why do you choose to write about children, from the child’s point of view or otherwise, and what about animals?

VAN WINCKEL

The child’s point of view and childhood in general are compelling because children witness us as adults, and that means they’re seeing a lot of fucked-up-ed-ness, and it’s, I’m sure, very mystifying. I remember the first time I saw my grandmother’s breasts and I though, “Oh, am I going to have those?” You’re trying to figure out how to read the world, and they’re your guides, such as they are. The whole dynamic is really interesting to me.

I remember when I was in tenth grade of so, and this social studies teacher was telling us this story about growing up in North Dakota and how his family lived so far out of town, as did a lot of the farming community there, that their kids couldn’t get to school in the wintertime. So they sent the kids to live in a hotel during the weekdays so they could go to school, and then they’d come and get them and bring them home on the weekends. Years later when I was working on that book I remember thinking, that’s fantastic. What a way to grow up. You’re living in a hotel with a bunch of children with very little supervision just so you can go to school. I put my narrator in Limited Lifetime Warranty in such a hotel with children. She’s just starting out as a veterinarian. At the time, my husband and I were raising a few sheep. When you raise animals like that, you do a lot of your own veterinary stuff, like the hoof-trimming and tail-docking. I had a friend who lived on a sheep farm, and she showed me the ropes. My way of catching lambs so that we could use the tool called the emasculator—I kid you not, this is an actual tool—was to throw myself upon them. They were so fast. I did have a shepherd’s crook, but I could never get the hang of it.

Anyway, I did spend a lot of time with animals, and I’ve had experiences in the woods with cougars, and, you know, wild creatures are about. I was just remembering that cougar experience. I was walking on some dirt road out by Liberty Lake, and there was this cougar right in front of me on the road. Oh my God, I was so afraid. And then we stared each other down for the longest time. Big stare down, me and the cougar. And then he just walked on across the road, very slowly, watching me. And he went on up, high, to this big ridge that overlooked the road, and he watched me as I walked, backwards, all the way to my car.

KEELY LEIM

Yes, that features in Curtain Creek. It’s a terrifying cougar scene.

VAN WINCKEL

Is that in there? Right, right, I did not bring the cougar back for that.

BUCKINGHAM

We realized a lot of the images come up over and over again. The fox stole is one of them, and I noticed textiles repeating themselves.

VAN WINCKEL

God, that’s so cool, I hadn’t really even thought about that.

ELIZABETH GRAVES

Zero comes up a lot, as well. What’s your interest in zero?

VAN WINCKEL

I like the sound of that word, zero. .But when writing Sister Zero, I was thinking about writing code—solid ones and zeros. Those were my only thoughts. Things kind of matriculate out of a poem and into a story, or out of a story and into a poem. And the stole, I just think it’s a riot that women used to wear those with the little mouths that opened and closed and hooked onto the tail. It’s kind of a moebius image. The poor fox can’t stay dead. I think my grandmother had one of those, and I remember buying one at a flea market and wearing it as a Halloween costume.

BUCKINGHAM

It’s interesting that these stories and images that are part of your consciousness and your subconscious have no bounds of form. It’s in a poem, it’s in a story, it’s in a digital thing—it’s not like, here’s this image, and therefore I have to write a poem. My question is about choosing a genre. It almost seems like the image, or the obsessions, are about the form, more important than the form.

VAN WINCKEL

I think that’s really true. They get in my deep subconscious somehow and emerge later. But it’s that question about how things decide if they want to be poems or stories that I often wrestle with. Oh my god, lately if I sense something’s trying to be a story, I’m like, please, don’t be a story, please, don’t, because it takes over my life for such a long, long time. I’ve got notes for one in my office right now. It’s so much energy, and I know if I start writing it, I have to just close off the rest of the world completely. It sucks everything out of me.

I’m deep back into poems again, but, going back to persona, when I was in grad school all the poets were required to take a fiction writing class and vice-versa. And as a poet when I took my fiction workshop, oh my god, the story I wrote was terrible, and I was pretty much laughed out of the fiction workshop. Mine was all, like, deep image stuff. It makes me cringe to think about how awful it was. It wasn’t until I started teaching Introduction to Creative Writing, and I’d be walking to class trying to think, was DOES this person’s story need? I was teaching myself to write stories, and I had no clue that was happening. And then persona in poems finally blew the door open for me to be more fully in a character’s perspective. Then shit started happening. This first book of linked stories I wrote, Limited Lifetime Warranty, I began on my drive from where I lived in northern Illinois into Chicago—an hour-and-a-half drive. On the passenger seat I jotted on a piece of paper five little sentences that became the first five stories in that book. They all came just like that: the situation, the character—the same character, the young woman who becomes a veterinarian, her coming of age.

EBELING

Could you talk a little more about how writing fiction has informed your poetry and vice-versa, and do you feel like the composition of one genre informs the other?

VAN WINCKEL

Okay, let me take your first question first, and then we’ll go back, because that’s my favorite question. Thank you. When I started writing stories, what happened was they sucked a lot of the narrativity out of my poetry, and I really like that. I appreciated that I didn’t feel I need so much “story” in the poems anymore, that stories could be their own thing and fleshed out, more imaginatively alive, and I didn’t have to drag all that into a poem. It was very freeing. I guess as an old person now, one of the ways I feel like I’ve kept going is that I keep finding ways to change up what I’m doing. The experiments I’ve done lately with visual stuff—Ever Yrs, for instance, opened up a whole other door, giving me permission to learn and experiment in a new discipline. I loved the challenge of that. It helps that I work in an environment where I have other writers around me all the time, and I go to their lectures. It’s great. I’m learning so much. For instance, I was out at Vermont College one summer, and a writer I really like, Pam Painter, who’s especially known for her flash fiction, was giving a lecture. She said, “If you’re writing flashbacks, try not to let them go on for more than two pages. Any more than that, we lose the momentum of where we were before flashback.” That’s a kind of boneheaded place I was in with my own fiction back then, and I so needed to learn exactly that. Just being around that kind of information feed all the time has been such a privilege.

BUCKINGHAM

Not only do you write in a bunch of different genres, but almost every book of yours I’ve read is cross-genre. Pacific Walkers is journalism and poetry, and Boneland is linked stories. There’s a crossover everywhere. Ever Yrs is a novel but also visual. And it reads like Book of No Ledge—it goes so many different places that the story line of novel feels less important than some of the other stuff.

VAN WINCKEL

Yes, the big challenge for me in that scrapbook novel, Ever Yrs, was the through-line.

BUCKINGHAM

Oh, that interesting that you had to think about that—so your instinct was kind of to play.

VAN WINCKEL

Exactly. Exactly. I think every book has presented its own “experiment” for me. For instance, with the linked story collections, each one has had really different linkages. That’s been part of what was fun about making those books—discovering how I was going to link them up. Especially the one with the woman who is getting cataract surgery.

BORDWELL

Boneland.

VAN WINCKEL

Yes. Those pieces where she’s up in Canada and she’s had the botched surgery were their own little story and published as such. So I ripped them all apart and made them into little flash pieces to go in between the other longer stories. I liked what happened when I spliced them; they gave the book a sort of grounding, “a looking-back” perspective that helped me think through the longer stories as I revised them.

BORDWELL

In that book, Buster has this incredible persona, and he’s there and then gone and we hear about him a couple times, but he gets that much depth even though he’s just one fragment of the whole narrative.

VAN WINCKEL

I love what you’re saying. Later, though, I wondered if what I had done with him was okay in terms of appropriation, since he seems like an autistic character.

BORDWELL

I think he was my favorite. As an autistic person, I found that story so poignant and accurate. It wasn’t just, oh, he’s good at math, and let’s talk about how he goes into a career in science. The dude becomes an ice skater and is the Beast in Beauty and the Beast on ice. That’s not the standard autistic narrative that gets pushed around. I found it really, really endearing.

VAN WINCKEL

I can’t tell you how much that means to me that you think that’s okay. Because I worried about that so much. This whole issue of appropriation. I have to remind myself, Nance, you can’t just take other people’s worlds and issues they’re dealing with. But then I think, well, shouldn’t people who have those issues, shouldn’t they get to be a part of fiction, too? I struggle with this.

BORDWELL

I found myself really moved by poems about or in reference to indigenous people such as the Inuit and the Apache in Bad Girl, with Hawk. Many early poets in my generation are afraid for very justifiable reasons to write about any people who aren’t their own, but I also see this as being its own kind of erasure or silencing. Can you speak to why you chose to write about cultures beyond your own, how you did so, and perhaps offer guidance to this new generation of anxious poets?

VAN WINCKEL

It’s hard to navigate when that inclusion thing steps over the line and you’re appropriating other people’s troubles as if you know what that life is like. I think it’s a tonal thing sometimes where one assumes an authority one does not have over the material. I guess my instinct has been to presence them in the work, to bring them in. It’s not about judgement or trying to suggest I know their lives, but rather that they are with us, part of the family, the larger family.

BORDWELL

Like the way Robert or Robbie in Boneland ends up being gay at the end. It’s that tiny bit of inclusion thrown in at the end that enriches the narrative and contextualizes his life, but he doesn’t have to be gay. Just like nobody in the book has to be straight.

VAN WINCKEL

Exactly, it just is. That’s one of the reasons I liked the grandmother in Ever Yrs. Her grown son is gay, and she is so accepting of that even though she’s been raised in the Christian church, and in a way her trajectory in that book is really my own, which is away from Christianity towards more acceptance of, let’s say, more humanistic teachings. She’s me when I’m a hundred. Getting there.

LEIM

On the subject of you and your life and how it intersects with your writing, how do you view your incorporation of certain autobiographical elements into your work? For example, the last chapter of Curtain Creek Farm with Francine features a mother who doesn’t always remember her daughter.

VAN WINCKEL

Interestingly, when I wrote that story about Francine and her mother. . .do they go to a strip club?

LEIM

The Elvis show.

VAN WINCKEL

The Elvis show, yeah! There’s a part in there when the mother says the ginger root looks like a penis. Yeah, that came from my mother. Definitely. There are a lot of things that I’ve taken from my family and from my friends. The whole Curtain Creek Farm book in so many ways. I don’t know if you guys have ever been out to Tolstoy Farm, the commune just west of Spokane. It’s one of the oldest communes in the US. It started in the early 60s, and one of my friends moved there around 1968, had a kid there, and when she comes to visit me, we trek out of there. I remember coming home from Tolstoy Farm with her, and I turned to her, she’s a writer too, and asked, “Do you think you’re ever going to use this place in your work?” She just looked at me and said, “You may have it.” So because I’m writing fiction, I moved it to a different location. But back to Francine for a second. When I wrote that story, my own mom was fine. She didn’t have Alzheimer’s. Not yet. I know. Kind of eerie.

BUCKINGHAM

Well, it seems pretty clear to me that writers have that prescience.

VAN WINCKEL

Okay, I’ll tell you a scarier one, then. So that book Quake. You know that last story where there’s that earthquake? I wrote that story and then my husband came home and I said, “Okay, I finished the book today,” and I gave him that story to read, and there’s an earthquake. A bridge collapses. And later that night we turned on the TV, and there had just been that earthquake in Northridge, California. That was rather scary actually. It feels sometimes like I’m in a dream space when I’m writing, like I wasn’t expecting to write about an earthquake. And then there it was. Complete with visuals. Then there it was on the nightly news.

BUCKINGHAM

The way you talk about fiction seems like that, too. “I don’t want to, I don’t want to, but it’s here at the door, and I have to.”

VAN WINCKEL

It wakes me up. In the morning when I’m working on fiction, I wake up, and there are people talking in my head. I tell my husband, “Don’t speak to me. Don’t speak to me. I have to go write this down.” It’s like your subconscious is still on the job while you’re trying to freaking sleep.

BUCKINGHAM

I wonder what role the mythic plays in your work because I see it all over the place, and it always surprises me. Even in Ever Yrs, that minotaur. It’s kind of misplaced. There is this super contemporary stuff on top of these old pictures, and then there’s this minotaur. And in Pacific Walkers there are archetypal characters.

VAN WINCKEL

I do like when that happens. I don’t think I consciously go there, but when I see that it’s percolating up, I may investigate its potential. That book is set in Butte. The whole minotaur thing seemed so apt. The city is set on top of a maze of intersecting mine tunnels. And then I saw that minotaur figure in some piece of graffiti, so I moved him into the book, too. It’s like when you’re working on something, poem or fiction, you’re in a mode where things around you are suddenly magnetized and pulled into the work. I’ve always liked being in that place. I feel like I have my antennae up, there’s things I’m looking for, but I don’t know what they are, and I’m in a waiting mode. I’ll never start writing a story until I have at least three or four fields of action, I call them, things I know that are going on simultaneously. Like different balls thrown in the air. I don’t even start writing until I have these balls to move between. If there’s only one ball in the air, anybody can do that. Two balls, still easy. But when you get three or four or five, things start to be really interesting, and that’s where I want to be before I write a single word. I need to have that sense of dynamic—of moving back and forth. Same for a poem, too, that sense of place, action, who’s speaking. Who is this person? I don’t work from the idea that it’s me, my own life. I’m just a suburban housewife, please. My life is boring, but my life in poems is way more interesting.

GRAVES

I was thinking about your visual poems. Can you talk a little bit about the process of those? Is it similar to having a whole bunch of balls in the air? They feel very intuitive.

VAN WINCKEL

I love that word intuitive, yes. I’ve moved ever so gradually into the visual realm: visual poems, erasure poems, collage poems. I think it’s because I love images so much, I realize, oh, these are actual, physical images. I want them! I must have them. But I need to be loyal to poetry and to literature because that sort of brung me to the dance. And I’m still a reader. I read all the time. The challenge in that, and what’s been fun about it, is to figure out how to integrate text into that visual space that feels more my own.

GRAVES

In your work, I was reminded of something that William Stafford wrote in Writing the Australian Crawl. “Writing is a reckless encounter with whatever comes along. We have to earn any moon we present. The only real poems are found poems, found when we stumble on things around us.” What do you think about serendipity in writing and art? Or what is the role of intuition or willingness to be open to receive the world around you?

VAN WINCKEL

Oh, I love that so much. Yes, I agree, and I think that’s part of what led me down the road to visual poems. My husband loves graffiti. He’s a visual artist, that’s how he makes his actual living, and so whenever we’ve traveled someplace together, I think because I had the purse—this is just so sexist—I carried the camera. “Nance, get the camera out, shoot this, shoot this.” Mostly he wanted me to shoot images of graffiti. He loves the bold vibrance of them, and I really came to appreciate them, too. So I would take all these shots of graffiti, but there would be text mixed in with it, and I love that, too. I remember one of the first ones I shot. I think it’s somewhere in Spokane. I started packing along the camera, even sans husband, just for myself when I was out doing my urban walking. And there was “Roo ‘n Boom love more than you.” I thought, okay, that’s a perfect little poem. So when I took that photograph I didn’t add any text because I loved that language it already had. To make it mine, to make that wall, that brick wall with graffiti on it belong to me, I needed to enter the conversation. So, instead, I added some imagery, a scene from the 1890’s of women in big hats, and then I made it look like it had been on the wall for a really long time. That was one of my first stabs at interacting with the graffiti. Usually, however, I try to add a few words just to be a part of the conversation on the wall, which is another thing that I like about graffiti. It’s a place for anybody. You don’t have to be famous to have your say. I can send you a copy. Is this going to be online? You can put it up with the interview. [See the bottom of the page for the image.]

BORDWELL

I’m fascinated by how The Many Beds of Martha Washington began as a single poem in Bad Girl, with Hawk. Can you speak to how and why the ideas of that piece stuck with you? How do some pieces or ideas sit with us for so long, and how do you know when to further explore them?

VAN WINCKEL

One of the things that’s influenced me is American history and folklore—folk stories. The stories of the folks. I grew up as a kid in rural Virginia. I remember taking the school bus, and there were all these signs around. “Martha Washington slept here.” I was just learning to read. And I thought, who is this person? And who cares? What is this about? Later, I found out who she was and that she and George had lived down the road from where I started school in Mount Vernon, Virginia. It felt like history was already kind of inside me. I spent a lot of time with my grandfather. He was the only reader I had as a model growing up. My mom read ladies’ magazine, and my dad, my stepdad, was not a reader. But I remember seeing my grandfather reading history books all the time. And when I went to college, he sent me all these letters that were often three, single-spaced, typed pages about our family and the battles they had fought in during the Civil War. We were one of those families that had people on both sides of the Civil War. And my grandfather, I think, was really torn by that. He wanted me to know who these people were.

BORDWELL

I’m curious about the role you see Martha Washington and other historical figures playing in your work and why there’s a drive to write about them so consistently. For lack of a better way to phrase it, why do we become obsessed with people?

VAN WINCKEL

Yeah. God, I don’t know. They enter your deep psyche somehow. They’re like dream figures. Especially people and stories that you read as children.

LEIM

Are there other historical figures who won’t lose their hold on you?

VAN WINCKEL

It’s more the wild, outlandish stories, the sort of manifest destiny idea we learned in junior high. I remember thinking, wow it would have been cool to be a part of a wagon train and travel across the country. I remember thinking that. The older I got, the more I thought, that would be terrible! To think you could just go into some other part of the world and say, “Okay, this place is nice. I like this spot on the river here. I’m going to call it mine.” So it’s more like talking back to some of those ideas that were shoveled into us as kids, especially these kinds of folk myths, that if you were strong and deserving and lived a good life you were owed X, Y, and Z. You had a right to it. The Butte story in a way is that same story.

BUCKINGHAM

All the mining going on.

VAN WINCKEL

The mining. Between Minneapolis and San Francisco, that was the most populated US town in the early 1900s. Butte, Montana. And now look at it. It’s a superfund clean-up site.

BUCKINGHAM

I have a question that relates to what you’re saying. When I read your work, I think of it as very subversive. I wonder how you see the role of politics in poetry.

VAN WINCKEL

I think a lot of poetry talks back to politics. As a writer, I can’t have an agenda going into it. The work needs to surprise me. But what you’re asking is definitely one of the things I use as a test. Does this have any relevance outside my own imagination, my own little life? What’s it speaking back to, or what does it call into question that maybe need to b called into question? Often I think I’m just raising questions.

Right now, for instance, an issue that confronts me daily and something I’m writing about is homelessness. We have campers all around, right? They’ve adopted my shed out back. They’re here, , really close. And it presents a very complicated issue for me. Because I’m afraid of them sometimes, and sometimes I take them a Coke. Seriously, I do. They want to use my hose to take a bath. I say, “Okay.” Fear vs. empathy. It’s hard to figure this out. So I simply ask questions, stay focused on the questions. But in terms of writing about it, I had to move it to another place. I had to move it to the city, New York City, where my husband and I used to rent a little B&B before or after my teaching stints at Vermont College. Homelessness there is really interesting, too. Homeless New Yorkers: if you don’t get out of their way, they’ll just give you a shove. My imagination seems able to work the questions better if I don’t use my own backyard. I feel like I can’t be as imaginative if I’m stuck too much in my own life.

BORDWELL

Since many of us are writing our first poetry collections, can you speak to your experience writing your first books? What guidance might you give to early writers, specifically today? How do you think first collections have changed since your own?

VAN WINCKEL

First collections have changed a lot. When I was starting out, a lot of people’s first books of poems were, much like my own, about their lives growing up and becoming adults: the struggles that one has with family, with family dynamics, charting one’s own path out of the first books I’m seeing, and I think maybe this is to the betterment really, are organized more as kind of project books. You will see some childhood issues and maturation, but with more of a through-line or central concept. It’s gotten harder than ever to get that first book out. Competition is really stiff now, thanks to all these writing programs. So a person has to have a very distinctive voice and style to set themselves apart, more than ever. And that’s good. If you can find that, that’s what you need to do.

My favorite thing to do with graduating MFA students is to help them make their book. In a poetry book, one approach is to find say four or five poems that are the main punchy poems and then make those central to a section, configuring the other poems in that section around that central poem. That’s just one way. As opposed to the student who years ago wanted to organize her book fall, winter, spring, summer, and I said, “No, please.”

Let’s make it interesting. Just get out of those clichéd traps. Find a line from a poem to be the title of the next poem—just little things like that give the book more cohesion. And I’m sensing that’s happening more in first books. They used to be like, “Here’re all the poems I wrote in graduate school, all the experiments that I did, and I learned so much. Here’s a sonnet, and here’s a villanelle, and then oh, here’s a five-page narrative poem in the middle here,” and oh my god.

BORDWELL

The way you describe it makes it sound like a very good change has occurred.

VAN WINCKEL

Yes, higher expectations. When I published Bad Girl, with Hawk, my first book, there wasn’t a single poem that I’d written in graduate school. Not one. And someone I went to grad school with—I’m not going to say her name, published her first book about the same time I did, and I recognized about half her poems from our workshop. She’s done fine though. She’s doing fine.

EBELING

We often talk about the emotional resonance of speakers and characters in both poetry and fiction. And since you compose both, I’m wondering if would you talk about the role of emotional investment in your readers across these genres.

VAN WINCKEL

Emotional investment, yes. Okay, I’m going cop to this because it’s true: the thing that makes me happiest is when I look out at the audience and see they’re crying. I’m pleased someone has been moved by something. That I’ve touched a nerve. I really think that sadness connects us in a much more deep-down way that happiness. About this new memoir book, Sister Zero, people have been saying to me, “Oh this happened to me, too. I know just what you mean.” Wow, connection. But you can’t just do sad. Nobody wants that. You need to have a range. And it’s the range that makes it work. For instance, in my memoir, since it was mostly so sad, I had to make myself put in Mr. Ed, the talking horse. It needed that counterpointing. I’ve noticed when I read things, if I read something humorous first and then I read a sad thing, the sad gets much sadder—probably because you weren’t expecting it. It’s because you went from an UP place into some down deep place. That’s the only way I know how to make emotionality work. I know I’m writing emotional stuff when I’m crying as I’m writing. this is a test. And I can’t tell you how often that happens. But I know I’m in a good place then. I know I’m hitting that nerve. I like funny though, too. I really like funny.

GRAVES

I wanted to ask about your experience working with or accessing memory. In Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir, she writes, “Memory is a pinball in a machine. It messily ricochets around between image, idea, fragments of scenes, stories we’ve heard. Then the machine goes tilt and snaps off. But most of the time we keep memories packed away. I sometimes liken that moment of sudden unpacking to circus clowns pouring out of a miniature car trunk. How did so much fit into such small a space?” Throughout this conversation, you’ve been reminiscing about things, too. I don’t know if you takes notes or keep a journal, or if these little memories just come back to you at the right time. How are you accessing them?

VAN WINCKEL

No, I don’t take notes, I don’t do journaling. I work on a yellow legal tablet, lined paper. It’s what I was talking about before with the antenna. I write down fragments. I’m not trying to write a poem. I’m just writing down some lines I like the sound of. Maybe two or three. Then I’ll go back, and I’ll read some more Charlie Simic—oh yeah, that line of his reminds me of something. Then I write that down. I’m not even going to put that line close to these lines. I’m going to start a whole other column and put that over there. To my mind that’s what Karr’s idea sounds like: that ricocheting. Then what I have is this giant freaking mess of lines: columns of them, nothing really connecting to anything else. But then, later, things start to forge connections. My antennae are up. As if on their own. I cannot write a poem if I give myself an assignment. I don’t like those. People have asked if I want to part of some, I don’t know, poem-a-day, or if I want to write a poem to go with a painting. I can’t stand that shit. Please. Poems do not come from assignments. A poem is its own little creature, and it grows. My lines are like molecules waiting to attach to other molecules. This sounds too weird, doesn’t it?

BUCKINGHAM

No, it’s very ricochet-y.

VAN WINCKEL

I love that ricochet word. Mary Karr is great. Reading is such a big part of it. I need to have somebody I’m reading who just gets my language synapses all fizzy. That’s what makes me write. And what I’m writing has nothing in common with who I’m reading except for I like their fizziness. I want to steal that fizziness.

BORDWELL

I discovered, upon my finishing the book, that of the 400 published copies of A Measure of Heaven that exist, I happen to own the 314th. This happens to be one of the only poems I’ve committed to memory, by Emily Dickinson. Number 314 begins, “Hope is the thing with feathers / that perches in the soul / and sings the tune without the words / and never stops at all.” When I saw that number, I thought of how often faith seemed to weave its way into your work, not just with the obvious A Measure of Heaven, but even in your fiction. I don’t mean faith in the traditional, religious sense, although it has that, too; instead, I’m thinking of an understanding of our place in the world, of hope in it. What role does hop and/or faith play in your writing? Does creative work change your own hope and faith? Does it reaffirm your own faith in humanity, or the Earth?

VAN WINCKEL

That’s just beautiful, Oran. What a great question. Yeah, definitely not religious faith, but faith in each other—the human family. That we’ll get through. We’re not going to all burn up. And you’re right. It’s really the work that pushes me to that feeling. Just the fact that people still want to read and go to literature for exactly that reason. Especially those of us who maybe don’t have a religious faith but have faith in each other. That we want to reach each other, and we want to share stories that somehow make the hard stuff beautiful.

LEIM

As a follow up to that, how do you retain that sort of faith in a post-2016 world?

VAN WINCKEL

I really struggle with that. I feel like I’ve gone increasingly to a really pure, imaginative space when I read and when I’m writing too. Something that’s not about endings. That doesn’t have endings. I come back to that idea of enchantment again. That’s sustaining somehow. That we can still be enchanted.

BORDWELL

It’s rare, in fact I don’t know if we’ve ever gotten to do this, that we get to interview someone who worked at Eastern and someone who ran our magazine. What do you think of as your favorite memory, moment, lesson that you gained or received, or taught even, at Eastern Washington University? Or specifically in the magazine.

VAN WINCKEL

One of the things that I loved doing when I was editing was the magazine layout and finding the cover art and art for the inside pages. That was such a delight. That was when I think I realized I could be lost for hours doing freaking Photoshop. The student taught me it. I didn’t know how to do any layout when I got there. And I loved our editorial meetings.

LEIM

I’d love to hear some of the name of writers who’ve companioned you, dead or alive, and what they’ve meant to you.

VAN WINCKEL

Yes. I definitely have my writers. People I return to. I’ve mentioned Charlie Simic, since I’m rereading him right now. Oh god, I love Dennis Nurkse, Norman Dubie. Dubie has really helped me think about persona. He goes into these other headspaces, like, who is this person. I really, really like Norman Dubie. I remember we were reading some of Dubie in one of my classes and I said, “Yeah, I like to haave a little Dubie each morning with my coffee.” They went, “Yeah, Nance we’ve heard that.” I’ve been reading James Baldwin. Laura Kasischke. Wallace Stevens. Oh my god, Wally. He’s somebody who’s pure imagination. Here’s this guy who’s a vice president of Hartford Insurance Company, and he writes these poems while he’s walking back and forth to the office. In his head. Gets to to the office. Writes them down. Those poems are full of sound. Talk about the fizz of language. That’s what Stevens was. That’s what drove him to poetry. Fuck insurance. Really, I mean, the guy had a bazillion dollars. He didn’t need to write poetry. It sustained his inner life. The life of the imagination. That’s what he wrote about. Because that was the thing I think was so worried he was going to lose. It was going to get sucked out of him by Hartford Insurance Company. So, yeah, the sustaining. We have to find out peeps. I remember when I was a freshman in college, where I was when I read some of these poets for the first time. My life felt altered. I remember lying in the top bunk reading a poem by John Berryman called “The Stewardess,” where she falls out of an airplane and dies.

BUCKINGHAM

That’s really funny.

VAN WINCKEL

Yeah, it’s funny in the poem! The poem is funny. It’s weird—her gloves are here, part of her is there. And then, there’s this poem of James Dickey’s called “The Sheep Child” where a guy is looking at something like in Barnum & Bailey, in a jar.

BUCKINGHAM

Oh, no.

VAN WINCKEL

He’s being told, “Don’t have sex with animals, this could happen to you.” But then, Dickey lets the sheep child speak. Oh my god, it’s amazing. That sense of otherness. Of being not this earthly realm, but of another realm. I remember what if felt like to go there with Berryman. Anyway, I remember all these people and where I was and how the world felt changed afterwards. I hope you guys have that same experience.