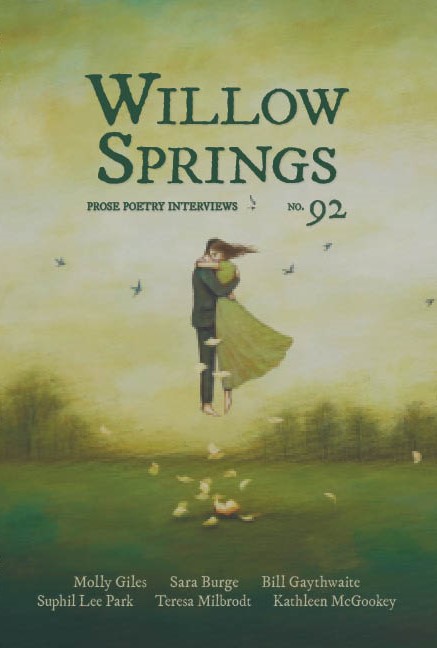

Found in Willow Springs 92

APRIL 8, 2023

ISADORA ANDERSON, POLLY BUCKINGHAM, BLAIR JENNINGS, SHRAYA SINGH, & ALISON WAITE

A TALK WITH MOLLY GILES

Found in Willow Springs 92

MOLLY GILES’ WRY AND QUICK-WITTED, observational voice has given life to female characters disenchanted with their circumstances and the underwhelming men that surround them. She is a master of the short form; her language is tight, precise, and caustic and her stories darkly comic. Her endings tum on a heartbeat, often surprising and always resonant as if they couldn’t have possibly ended with any other configuration of words and emotions.

Giles is the author of five short story collections, the first of which, Rough Translations, was awarded the Flannery O’Connor Award for short fiction, the Boston Globe Award, and the Bay Area Book Reviewers’ Award. The stories were described by the Houston Post as “tiny gems, carved from real American life, precise and identifiable.” Giles’ other collections include Creek Walk and Other Stories, winner of the Small Press Best Fiction Award, the California Commonwealth Silver Medal for Fiction, and a New York Times Notable Book, originally published by Papier-Mâché Press, reissued by Simon & Schuster in 1998; All the Wrong Places, winner of the Spokane Prize for Short Fiction (Willow Springs Books, 2015); and Wife with Knife, winner of the Leap Frog Global Fiction Prize Contest, 2020. She has also published two novels, Iron Shoes (Simon & Schuster, 2000) and The Home for Unwed Husbands (Leapfrog Press, 2023). Her autobiography, Life Span: A Memoir, is due out through WTAW Press in 2024.

Giles’ work has been included in the O. Henry and Pushcart Prize anthologies, and she has received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Marin Arts Council, and the Arkansas Arts Council. She has taught fiction writing at San Francisco State University, University of Hawaiʻi in Manoa, San Jose State University, the National University of Ireland at Galway, the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, and at writing conferences, including The Community of Writers and Naropa. Molly has also worked as an independent editor for many authors, including Amy Tan.

We met with Molly Giles on Zoom on Saturday, April 8th to discuss how her shift from poetry to short fiction, the unlikely circumstances that started her teaching career, seances, and the inspiration behind her work—including which stories were overheard, divulged, or completely fabricated. In a serendipitous turn of events, several of us had the pleasure of a second meeting with Molly Giles at the Community of Writers conference in Olympic Valley, California where Giles was on staff. This time, Giles was the one asking the questions. Giles was exceedingly thorough and generous with her feedback. Her command of story structure, pacing, and knowledge of exactly when to include a humorous quip was sincerely appreciated. Some of her signature zingers you’ll find throughout our conversation.

POLLY BUCKINGHAM

How are you doing? I know you had hip surgery recently.

MOLLY GILES

Yes, both hips are full of hardware now, but they’re getting me where I need to go. I do walk with a cane, and I’m trying not to point with it. One of my friends said, “It makes you look like an old lady,” and I thought, well yeah. I like my cane. I would like to have a little stiletto on the end of it.

BUCKINGHAM

Like Ida’s wooden leg.

BLAIR JENNINGS

Ida in Iron Shoes and The Home for Unwed Husbands has leg issues. I was wondering if your leg issues might have inspired that.

GILES

No, not mine. But my mother was a double amputee; she was very brave about it, though she did sometimes take her prothesis off and wave it at the grandchildren.

BUCKINGHAM

That leg up in the top of the closet after Ida dies—I couldn’t help but think of Flannery O’Connor.

GILES

Yes, “Good Country People.” That is a great story.

SHRAYA SINGH

What’s your favorite piece of your own work that’s been published so far, and why do you like it?

GILES

Probably the very last story in Wife with Knife, “My Ex.” It’s about how you feel after divorce—that combination of fond nostalgia and absolute fury and continued incomprehension. I’ve been divorced twice, and I wish I could divorce both exes again. Once wasn’t enough. So the enigma of the relationship continues long after the relationship itself. That story is two pages long and and took me two months to write. I was very happy with the end.

BUCKINGHAM

I’m so impressed with your endings. Even in Iron Shoes, there’s that turn where she discovers what a louse her husband really is. In the writing process, where do those turns come from? Do they come late? Do they come early?

GILES

I think they come late. That’s a good question, Polly, because it’s so hard to answer. My main trouble is with beginnings. I think there were about fifteen first chapters to Iron Shoes. By the time I got into the world of it, I could see my way better. When I start a novel. I have to ask, is this going to be a tragedy or a comedy? ls there going to be a wedding at the end or a funeral? I know what direction I’m going in, but I never know where I’m going to end. And in novels the big pressure is to have somebody end with some form of acceptance or redemption, even though that’s not often true in real life.

BUCKINGHAM

Before you came in, we had a long discussion because I had read Iron Shoes and they read The Home for Unwed Husbands.

SINGH

We were wondering about the overlap of characters and whether it was going to be declared as an official sequel.

GILES

I think The Home for Unwed Husbands can stand alone, and, to tell the truth, when I wrote it, I never had the guts to reread Iron Shoes. Iron Shoes is a dark book, and I wanted this one to be a comedy. It started off as a comedy, and then my ex-husband moved downstairs, and it didn’t stay funny. He lived with me, in the basement, but I worried about him all the time, and a light-hearted romp it was not.

BUCKINGHAM

The beginning of Iron Shoes, Ida with her legs cut off, is just so gruesome. It really brings you in. And there’s that piece at the end where Kay remembers the games she played with Francis—it’s a tender memory but the games are terrible, really mean. So it’s not one-hundred percent redemptive. It’s still pretty dark. You know she’s not done.

GILES

That’s why I felt Kay needed another book. She’s still under her parents’ thumbs; she still hasn’t grown up. I felt Ida needed more time too. She has a lot of my mother’s characteristics, but my mother was so much nicer. And the Kay character is sort of based on me, but I’m not half as nice. I have never been as generous nor as thoughtful, no. Most of the characters I made worse, and Kay I made better. I think that’s an author’s prerogative, right? I hope that The Home for Unwed Husbands can stand alone but I would love it if it leads anyone back to Iron Shoes.

SINGH

You said that divorcing someone once wasn’t enough, and I think I remember reading that exact line in The Home for Unwed Husbands. I remember underlining it and thinking, this is pretty funny. I wanted to know why you write about so many unsuccessful romantic relationships and marriages.

GILES

Revenge.

SINGH

That’s a great answer.

GILES

I have a little candle that says lucky in love, and in many ways, I have been. I stress the bad parts because I was raised to believe that only trouble is interesting. That’s what we used to be taught when we were writing. And I find it’s pretty true. So I do stress the negative. I do no accent the positive. My present partner could not be sweeter or lovelier, but I can’t write about him—there’s nothing to say. He’s perfect. So no, it’s hard. Don’t ever be too happy. It’s not good for writers to be too happy.

JENNINGS

That’s good new for all of us, I think.

GILES

Are any of you poets? I mean, poets make a career out of being unhappy.

ISADORA ANDERSON

We know you used to write a lot more poetry. What impact did that have on writing fiction?

GILES

I never published a poem until maybe ten years ago. I love poetry. I read it constantly as a child. But the poets I was drawn to were telling a narrative. I loved T. S. Elliot, not because of “The Wasteland,” which I still don’t understand, but because of J. Alfred Prufrock, a character I related to. As a child, I loved Tennyson. I think if I went back, I would still love Tennyson. I loved Edna St. Vincent Millay—I’m not ashamed of that. I think “The Ballad of the Harp Weaver” is gorgeous. And later on, I loved Dylan Thomas and William Blake. A poet I still love and read is D. H. Lawrence. I love his poems about animals. But I recently took an online course about W. S. Merwin. The course was taught by two other poets. And what they loved about Merwin is that they didn’t understand him, and they went on and on about how great it was not to understand things. I think Kevin Mcllvoy said the same thing [in a previous Willow Springs interview], how he loves chaos. Not me. I am the sort of person who, if I start a book and get anxious about what’s going to happen, I have no qualms turning to the last page just to find out if they live or if they die because, otherwise, I will not be able to continue. After I know, I don’t give up the book unless it’s badly written. But I do like to have all my anxieties soothed. I still love W. S. Merwin, even after six weeks of failing to enjoy not understanding him.

BUCKINGHAM

I do think poets, in general, are happier in uncertainty than fiction writers are.

GILES

Definitely. The one poem I did publish, about ten years ago, is the last piece in Bothered, “Young Wife on the Arc.” I rewrote it as prose, dropping the line breaks but keeping the rhymes. I didn’t start writing short stories until my late twenties. I was married, I had two children, and I was living in Sacramento. I didn’t know any other women who wrote or read. I felt isolated and depressed. I took a correspondence course through UC Berkeley, which was wonderful training. I wrote my first short story through that correspondence course and sold it to a magazine that promptly went out of business the same month my story was slated to come out. But I was able to submit that story to the Community of Writers, and they gave me a scholarship. So I was thirty by the time I was around other fiction writers—it was heaven.

BUCKINGHAM

Can you talk about the shift in your work from short stories to micro-fiction?

GILES

In that correspondence course, the teacher made me count my words. One piece had to be five-hundred words, another could only be twenty-five words. It felt a little artificial, but I was amazed by how much I liked compression compared to expansion. I’m drawn to the shorter forms of prose. My pieces tend to be narratives. I want them to be understood. When I read somebody like Lydia Davis, I am impressed by the intelligence but often puzzled by the story.

The first flash piece that really worked for me was ‘The Poet’s Husband,” which was written maybe thirty years ago. It was based on going to a poetry reading and watching this beautiful young woman get up and talk about everything that her husband and she shared. And he just sat there nodding and smiling, and l thought, my God. I don’t know about you. but if somebody I’m close to gets up, for instance, and starts to sing. I blush. I’m terribly embarrassed for them. But this woman was very self-confident, and she was talking about her affair, her suicide attempts, her unhappiness. And he just sat there smiling. That’s what inspired the story.

BUCKINGHAM

I want to ask about the title story in Wife with Knife. There’s this adage in writing, you have to write four hours a day, or however long, every day. But “Wife with Knife” suggests that this is perhaps a male perspective. Some writers I love, Tillie Olsen and Grace Paley, have small but mighty bodies of work. They never had a time in their lives where they could write all day every day. They couldn’t afford that. One thing I heard your story saying was that this is kind of a myth; it’s not that people don’t do it, but it’s kind of a selfish thing. The life we live is important enough that we have to live it, and that doesn’t necessarily give us long writing periods. But it does give us the writing. In an interview you said something like, “I’ve raised kids alone, I’ve had a gazillion jobs, I’ve taught, I’ve edited, I didn’t have time to write every day. That isn’t my process.” Could you speak to this?

GILES

I’ve never been able to write every day. I mean, I got married at nineteen. I had children right away. I’ve always had to work. I didn’t go back to school until I was in my thirties. I was working different jobs all the time. I only started teaching at forty because my professor was an alcoholic and couldn’t finish the course. The chair of the department didn’t know who to ask and he just tapped me. I stepped in and was there for the next thirty-three years. As a teacher, I wrote mainly in July. As a young mother, when the children were little, I wrote during their naps. I have scraps of ideas on the back of utility bills that I’ll find stuck in my purse. I’m talking to you now from a cottage on my property that I used to rent out. I recently took it over as a writing room, and I feel guilty about it. I don’t come out here very often. I’m retired now, the children are middle-aged, I’ve got what I always longed for, a room of my own, and I’m still scattered.

I do better with deadlines. Rough Translations, my first book, is my MA thesis. It was done because the stories were due in workshop. In our real lives, nobody’s standing over you saying, “We have to have this.” Nobody cares. Unless you’re Stephen King. Well, Stephen King writes every day, even on Christmas, so he doesn’t count. I’ve always had a lot on my plate until now. And now, I have everything I’ve ever wanted, which is part of my philosophy in life—you get everything you need, just never when you need it. I finally have this great space. And I’m coming to the end of my career. I doubt I will ever write another novel. I want to get my memoir out. And I’m still writing short stories. But the energy for a novel is not there. There is irony in almost everything, I’m afraid.

When the University of Georgia press nominated Rough Translations for a Pulitzer Prize, they wanted to interview me. I got a phone call from a guy with this lovely southern drawl: “Now,” he says, “I’ve noticed that you started college in 1960. And I noticed that you finished in 1980. That’s a lot of unaccounted-for time.” And I thought, yeah. But unaccounted-for time is often a woman’s world. Often a man’s, too, but I think more of a woman’s. Now that I have nothing but time, I find I’m addicted to the New York Times spelling bee. That takes at least a half hour every day. And then I garden, I putter, I cook; I’m enjoying myself. I love life. But no, I’m not sitting down and writing four hours a day. I never have.

I think it was Grace Paley who said her best advice to writers was “love your life.” And I think Keven said the same thing in his interview. He said to look at what’s around you and pay attention and be mindful to what’s actually going on in your life. All of us here could write a Russian novel just about what’s happening since we got up. If you think about all the stuff that’s been going through your head and the people who flit in and out of your consciousness and what you see on the street, it’s all material. It’s just hard to pay attention to all of it—you’d go nuts. But it is there.

ALISYN WAITE

You mentioned your memoir. To what extent do you draw from your own life in your writing? I know some authors like to keep things very separate, where others prefer to be open about the fact that the story is based on their lives. Do you have your own balance?

GILES

Yeah, and it’s a balance. “Wife with Knife” was literally me listening to a friend talk. I listen hard to my friends. A lot of my stories are stolen from people who are naïve enough to trust me with their stories. I don’t think you can edit yourself out of every story—I’m in about half, I think. The memoir is all me. I’m trying to be as true to my life as possible. I was born in San Francisco, and the book is based on crossing and re-crossing the Golden Gate Bridge. It is titled Life Span and is comprised of flash pieces—none of them are longer than three pages—every year from 1945 to the present. It will come out with WTAW in 2024. It’s amazing to me the things that have happened on that bridge and the relationships I’ve had. One thing I still have to do is go through and soften some of the portraits of the people I’ve known. I don’t want to hurt any-body. I know I don’t like looking at myself depicted in other people’s writing, especially not my own. As I said earlier, the character Kay is based on a really nice Molly—I was never that good to my parents. I’ve always been snippy, and I’ve always been lazy.

BUCKINGHAM

We all have a hard time believing that.

GILES

Don’t. I can think of specific stories in Wife with Knife where I could say, “Yes I’m in there” or “No I’m not.” “Accident,” that happened to me. I was rear-ended in Arkansas, and I had such mixed feelings about living in the South. I was dating a guy at the time who was a musician. He was ranting about the Yankees, and I said, “Do you think I’m a Yankee?” And he said, “Oh no. You’re a foreigner.” Because the South was foreign to somebody who’d grown up in the Bay Area. I made the character much younger than I was and gave her a different life. But the incident happened. “Church News”—I do apologize. A friend told me that story, and I went and wrote it. And then I tried to get her to say, is this ok? And she wasn’t sure. Still isn’t. “Deluded” is cruelly based on a friend of mine who doesn’t read. “Assumption” is sort of a rural myth about a body tied to the top of a van. I nabbed it. “Dumped,” I didn’t even change the names. I just used my friends. “Life Cycle of a Tick” is very much about a relationship I had. “Not a Cupid”? I was once on a bus in Mexico, and I saw a woman, an American woman, petting this sullen little boy who looked trapped. “Just Looking” was about doing all this weird shopping but never buying anything. “Eskimo Diet” is a fairy story. “Married to the Mop” was about a time I cleaned houses but the character isn’t me. “Banyan” is me. “Ears,” me. “Paradise,” a friend of mine who talks to spirits all the time. “Rinse, Swish, Spit”—I live in terror that my dental hygienist will read it. “Two Words” was based on a tenant I had. I was sitting here in the cottage—I would come back in summer and stay in the cottage and rent my main house out when I was teaching in Arkansas—wondering what on earth to write about, and I saw this little, fat, naked man run out to the garden. He wore a pink feather boa around his neck, and he picked up a garbage can lid and started fighting the deer in my yard and I thought, Okay. “Underage” is totally autobiographical. “Hopeless” I made up because I liked the little kid in it.

JENNINGS

I’m curious now. What inspired “Talking to Strangers”?

GILES

I live at the foot of Mount Tamalpais. A few years ago, a serial killer was on the loose, violating women hikers and murdering them on the trails up there. I loved hiking that mountain alone. When I realized I couldn’t do that anymore, I felt angry. I was sitting at my desk, trying to finish a grad school assignment, and the first lines, it was scary, came to me. It was like somebody was speaking directly to me. It was the only channeling experience I’ve ever had. It’s something writers pray for. I heard this voice, and I just followed it. “I know you don’t know me,” the voice said. And I knew it was a dead girl speaking. I don’t read that story at conferences because it’s triggering. There are too many women who have been assaulted.

The only other time I’ve ever had a visitation, if you will, was at the end of my most anthologized story, “Pie Dance.” I had no idea how I was going to end it, and it just came to me. You write forty different ends, and you think, I can’t I can’t I can’t. And then it just comes. You had asked earlier about ends; that end was a gift of grace. It’s not going happen if you’re not there. You have to be with your story; you have to sit with it. Sometimes, magic happens. And sometimes it’s black magic. I’m not a spiritual person, but those were two times where I just didn’t know what to say except, “Thanks.”

JENNINGS

I’ve been known to write some dark things. It can affect my mood and throw me into a very deep depression while writing and a couple weeks after. I’m wondering how you get through that and still edit it enough to make it turn out well-crafted.

GILES

I think I’m shallower than you; I don’t stay depressed long enough. When I am depressed, I write. If I can’t create, I journal. I have journal after journal, and they’re all full of crap. The self-pity is incredible. Pages and pages and pages of it, since I was nine. I think of my journals as my puke bags. My daughter has promised me she’ll burn them all when I pass. I’m always horrified when someone like Hemingway dies, a beautiful writer who chose one beautiful word after another, and then when they aren’t there to revise, their journals or their rough drafts are published. You know, it’s just not fair. It does a real disservice to the writer.

I’ve only had a real depression once in my life, and that was because I wasn’t writing, wasn’t reading, wasn’t going to school. The children were little, and I couldn’t take care of them. I cried a lot, and I thought about getting rid of myself. I was in my late twenties—I think the twenties are a terrible time. People in their twenties need to know that things get better. You lose your looks, you lose your hips, but things get better.

BUCKINGHAM

I’ve been thinking about John Cheever as you’ve been talking and how some of your perspectives are kind of opposite. I love John Cheever, but he had the writing cabin and the ability to go, “Well, I’m off to the cabin and Mary and the kids can fend for themselves.” And also, he wrote his journals to be published, and then they were.

GILES

Well, they’re wonderful. I love those journals. They break your heart. And I love his stories. He does something I admire—he’ll leave the here and now, and slip sideways into fantasy. He does it effortlessly. I’ve tried that a few times. I don’t always get away with it, but I do admire the way he did it.

BUCKINGHAM

Yeah, I saw that in Iron Shoes with the fairy tale and with the blue horse. Like Cheever, you’re also writing about a time period in which the cocktail party is really big, and these casual cruelties to children are part of the culture. I wonder about those casual cruelties younger people might be appalled by, and whether the world has changed.

GILES

My three daughters all have children, and I’m looking at the way they have parented; they’re so good at it. My parents came out of the Depression and out of the war, and they wanted their own lives. I think they felt they never had a chance. I was writing more about my parents’ generation than my own generation, which is a generation of dopers and maybe inept parents but not cruel parents. I don’t think we really took parenting seriously. I had my first daughter when I’d just turned twenty; there’s a picture of me holding her on my hip like she’s a football I’m about to dropkick.

Somehow, all three of my daughters turned out great. All are professionals. One is a geneticist in Amsterdam, another a cannabis publicist, another is an attorney. They are wonderful parents: tolerant, loving, interested in their children. The granddaughter who’s living with me now, twenty-one, is going to go home and continue to live with her mother and father in the Netherlands when she goes to college. I would no more have lived with my parents after the age of eighteen than I would have flown; it was unthinkable to me. I grew up in the forties and fifties and my parents had better things to do than parent. It was like that Philip Larkin poem, “They fuck you up, your mum and dad.” And it all goes back to the mom and dad’s mom and dad, so you can’t assign blame. You just try not to repeat the same patterns with your own children.

JENNINGS

As I read your stories, I thought, all these men are so horrible. I’m wondering whether you’ve seen a change in men as well. Are they any better, or are they still the same?

GILES

I think men get better as they get older, and the testosterone dies down. If we could get rid of testosterone for a week, you know how easy the world would be? The Middle East would come together, the Ukraine war would end, the population explosion would slow. It’s a terrible, terrible hormone. I found that I at least can talk to men more after the age of fifty-five; they’ll talk to you about what they’re cooking, what their shopping list is like, their aches and pains. They’ll open up. The men of my generation were singularly silent. I remember reading Saul Bellow to find out what men thought. It wasn’t clear to me that men did actually think because the men in my acquaintance were charming in many ways, but mute. It was very frustrating. I remember thinking, especially in the D. H. Lawrence novels, florid as they are, oh, this guy’s thinking about something that I’m thinking about. It was new to me. I think men are chattier now. I hope so.

One of my early stories is “A Jar of Emeralds.” I was married to this beautiful guy, he was just lovely, but he never talked. And one morning he woke up and turned to me and said, “I feel like a jar of emeralds,” and I thought, wait a minute, who is this guy? I want to know him. He’s a treasure chest I don’t have access to. I do apologize to the male characters I write about because many are one-dimensional cartoons. I’m very aware of that, especially in the last book; I meant it to be a comedy, and I wasn’t looking for rounded and deep characters.

ANDERSON

Regarding the unwed husbands, I found myself so frustrated with all the men anytime they spoke to Kay, Neal constantly calling her “Babe,” Victor being religiously judgmental, Francis disapproving, and Fenton just not saying anything. How did you ensure that each unwed husband sounded different and interacted with Kay in a different way, and what was your process for writing the dialogue for each one?

GILES

Fenton was easy because, as you say, he doesn’t speak. I deliberately gave Francis the best lines because he’s just plain mean. He’s a terrible human being, but he cracked me up. With my own dad, if you’d hurt yourself—say you’d fallen down and scraped your elbow—he’d stomp on your foot and say, “Now how does your elbow feel?” It was that kind of Irish “humor'” I grew up with. Neal was the easiest because of the irritating oh Babes. I’m really embarrassed about Victor.

Biff was easy. I really liked the guy Kay met in Greece. He was nobody I had ever met, and I liked it when he talked. But I got rid of him fast because he was going to take over.

SINGH

You mentioned that all the characters from the most recent novel are like cartoons or caricatures, and they’re meant to be really unlikeable. Do you have any advice on how to write unlikable characters but still have your reader engaged with the material?

GILES

I guess the best advice would be to try and be that person. Every character in a story has his or her own motivation, their own sense of justice, of who they are. To try and actually be your antagonist and try to see things from their point of view takes a real leap of faith, but I do think that listening hard helps, and knowing your character’s background. For each of those characters, I wrote a couple of pages on where they were born, what foods they liked, what they wanted to be. I tried to understand who they were. It didn’t make me like them, but it did help me see where they were coming from.

JENNINGS

The short story “The Writers’ Model” has the fascinating concept of women being physically examined and questioned by male writers who want to write authentic women yet never overcome their false impressions of them despite their interrogations. This reminds me of a discussion among liberal creatives right now. Do we only write our own gender identity, sexual orientation, disability vs. ability, or race so we don’t accidentally write something offensive because we can never truly understand another lived experience, or should we become as educated as possible about what each type of lived experience is like and write as many inclusive characters as possible with the guidance of one of those who’ve lived similar lives?

GILES

You guys are really walking on eggshells in your generation with this stricture you’re under, to be authentic, to only write your own gender, to only write your own sexual preference, to only write your own nationality. It seems so unfair. You want to be careful, yes, but the imagination was given to us. It’s a great gift. I just can’t imagine having to stick with yourself all the time—who wants to? It’s wrong. I think that’s one of the great delights of slipping away from reality and writing fantasy because if you write fantasy, you can have green people and pink people and purple people, and you’re not offending anybody. You can actually say what you want to say about the world. I don’t write it myself. But I think of a writer I adore, Ursula LeGuin; through fantasy she can say things about the world she couldn’t say otherwise. My feeling is, thumb your nose at the authorities and write what you want to write. I don’t know what workshops are like now, but I’m sure they’re scary as shit because everybody is saying, “You can’t say that” or “You can’t say this.” I find it very Soviet. I don’t like it. Be mindful of others in your speech, and to hell with them when you’re writing. I am delighted that it’s opened the door to trans writers, and I’m really glad that I’m reading things that weren’t available to read even ten years ago. There’s so much new, fascinating stuff coming out.

ANDERSON

How do you balance withholding information to keep the suspense while at the same time establishing trust with your reader so that they are along for the ride no matter where you’re taking them in the story?

GILES

Wonderful question. That’s part of the reason why we can’t teach writing. You’ll know when you get into a story yourself what to do, but it’s really hard to come up with a rule for anything. I love workshops, mainly for the comradery and the deadlines, but there are some things I don’t think I’ve ever been able to talk about or teach, like tempo in a piece of fiction. You can look at the way other people do it. I love Alice Munro, and I’ve been looking at the way she withholds information, and I thought, I’ll take one of her stories apart and study it; that’s easy. But you can’t really diagnose her; she’s too sly. It’s up to you as a writer to feel your way towards what you need to do. And cover your ears—try not to listen to what other people tell you. To deliberately withhold and then put it in there later is very mechanical, and that’s not the way we work. I taught for thirty-three years saying, “Show don’t tell.” I don’t believe that anymore; I like to be told. We used to diagram things on the blackboard about how a story arc should go. That’s a bunch of hogwash; I never did like that.

I don’t envy anybody teaching creative writing now, but I love creative writing classes. I love the community that comes together; I love the way people push each other and inspire each other and give each other heart and hope. I’m in a writing group now. Almost every writing group I’ve ever been in or every class has a certain undefinable magic just as writing itself does.

WAITE

Can you talk more about your own experience teaching?

GILES

I stepped in scared to death. I was so conscientious the first three years that I would write single spaced typed pages of my critiques of the stories. Students would just throw them out the window as they went, and I don’t blame them. I don’t have a good speaking voice. I was often told to speak up. I had been reading more than I had been talking, so I couldn’t pronounce words. Oaxaca, I couldn’t pronounce it. I couldn’t pronounce quaaludes. Students would help me a lot. What I loved, and still do, is the fact that when you’re teaching a creative writing class, you’re getting to know people in an intimate way that you couldn’t if you were teaching history or chemistry. That is a real gift, that willingness to be open. Most of us are pretty shy in person, but in writing, you can access each other. I always liked giving prompts. The prompt that has always worked in class is to write for twenty minutes with just the phrase “My mother always” and then follow with “My father never.” The responses are amazing.

By the time I retired, I was developing an allergic reaction to student papers so I knew it was time to quit. I know I could never have mastered remembering who’s they, who’s them, and I would never want to be insulting to anyone in the class. I call my children by the wrong name; I’m sure I would get everybody’s gender mixed up. And I didn’t want to be that politically aware because I’m not. I was tired of teaching. I had said everything I had to say. So, time to quit. But I still love looking at individual stories and telling people what’s wrong with them, especially if there’s a way to fix it.

BUCKINGHAM

Have you done work with other writers like you did with Amy Tan?

GILES

I worked with Amy for a long time and it was a joy. I’ve worked off and on with Susanne Pari, whose wonderful second novel just came out, In the History of Our Time. I read my friends’ manuscripts all the time. I’m still getting letters from students I taught twenty years ago who are now just getting published, and that gives me so much hope. They might be in their late thirties, early forties because it takes a long time. They make me proud.

BUCKINGHAM

You’ve published with both smaller and bigger presses, and Amy Tan is with really big presses. What is your sense of the contemporary publishing landscape and where we’re headed?

GILES

I don’t know what’s going on in publishing today. I do think books are vastly overpriced. Amy Tan is a phenomenon. Few writers hit the big time so fast—she’s an excellent writer and has earned every accolade, but she should not be taken as the norm. Many excellent writers fail to succeed in publishing. They may never get used to rejections but they do have to live with them. I’ve had more rejections than I can count. After an especially bad siege of them, I’ll just stay in bed for an afternoon and then get up, rewrite, resend. They never feel good, rejections.

It seems to me it’s women my age who buy books. Bookstore readings are filled with middle aged and elderly women. I go to a lot of readings, and I look around and everybody has gray hair. That’s not true of the less formal open mic and coffee and dive bar readings I like to go to; they are buzzing with energetic youth. I want to support writers, so I buy. I get to take it off my taxes. I probably buy $3,000 worth of books every year. I’m trying to think of what I’ve just bought. Solito by Javier Zamora. It’s nonfiction. There seems to be a trend towards nonfiction. And there’s a real trend, of course, for émigré stories. This is about a nine-year-old boy from San Salvador who gets to America on his own. It’s very moving. Are any of you writing for television? I would urge that, or movies. There’s a market for writing games. Writing short stories is great, but it’s no way to make money.

BUCKINGHAM

There’s some really brilliant writing on TV right now.

GILES

Yes, The Wire is beyond brilliant. Sopranos, of course. I think when everybody’s out of the house later today, I’m going to watch Succession, but I’m not going to tell anybody.

SINGH

Succession is so painful to watch.

GILES

Because they’re horrible people. They make my characters look like angels.

BUCKINGHAM

What’s the difference in the process for you between a novel and a short story?

GILES

I love reading novels. But I like writing short stories. Both of my novels have been written like a series of short stories where one, hopefully, flows into the next. I’m trying to think of a novel that I’ve loved that has that flow in it. Oh, I know. A House for Mr. Biswas by V. S. Naipaul. Oh my gosh, it’s so good. I recently read a short book by a black writer, she’s gorgeous. Gayle Jones. The Bird Catcher. It was like reading jazz. And Claire Keegan’s Foster. Perfect. I like all the Irish writers. I love Sebastian Barry. Niall Williams’ This Is Happiness is a wonderful book. I can’t get enough of them. I just think they’re onto something. I listen to novels a lot when I walk. I’m listening to The Rabbit Hutch now. But in answer to your question, the difference between short and long. I don’t have the vision, really, for a long novel. I’m not a long-distance runner. I like to go a block, sit down, have a cup of coffee.

WAITE

In an interview with Emily Wiser, you mentioned that the voices in Rough Translations are “pretty naïve, self-conscious, and smartass.” How has your narrative voice changed throughout the years? How would you describe the voices of the characters in your more current works?

GILES

I do think the voices are smartass in Rough Translations. Then in Creek Walk, I was mainly writing about death, divorce, and depression so it’s a darker book. I think what I’ve done as I’ve continued to write is experiment with other people’s voices, rather than with my own. If you hear your own voice on your answering machine, don’t you just hate it? I think it’s still probably smartass, but older. I’ve always doodled. And I’ve always doodled the same woman’s face. The woman’s face has aged. I think I do have a distinctive voice. But I don’t want to know what it is. I don’t want to be told, either.

JENNINGS

The Home for Unwed Husbands has gothic horror elements, even though it’s definitely not gothic horror—castles, ghosts, mental health issues, toxic relationships, and unresolved trauma. What inspired you to use these things?

GILES

I don’t know if people are still reading fairy tales, but I definitely grew up on fairy tales. And I do believe in ghosts. So it was natural to me.

BUCKINGHAM

I want to hear more about ‘”I do believe in ghosts.”

GILES

Oh, don’t you?

BUCKINGHAM

I totally do. I see that a little bit in your work. I’d love to hear more.

GILES

Well, I’ve lived in an old house for over forty years. It’s in a little rural community off the highway. l was told it was a bordello. And then I was told that it was a train station. I’ve always had this feeling of people passing through it. Years ago my youngest daughter came to the door and said, “Mom”—it was about three in the morning—and I realized the temperature dropped maybe forty degrees; it was freezing. I said, “I know. Get in bed.” And we sat there and huddled. We felt whish whish whish going through the room, and then it disappeared. I think it was a traveler, either that or a prostitute, and it was on its way out. When I was three or four I woke up in the middle of the night, and there was a goblin sitting on my feet. I went to grab it, and I could feel it twisting out of my hands. I believed far too much in fairies as a child. I know I did. At eleven I was still looking under creek beds. That’s one reason I loved teaching in Ireland. They actually have little fairy wells in the hills. Probably for tourists and children, but they worked for me.

I’m writing a short story now about a writers’ séance. A poet sitting next to me had brought a photograph of this pretty woman in a fur coat. The medium was a frazzled blonde who warned us that we might be contacted by the dead via a physical sensation, our hearts might catch or we might feel a pain in our lungs. Then she closed her eyes, said we were surrounded by spirits, and began to say things like she saw a windmill over the head of a certain famous writer whose upcoming trip to the Netherlands had just been written up in the society pages or she heard someone calling out a message in Spanish to the writer from Latin America. I thought, what a crock. And then suddenly, the poet next to me with the photograph, myself, and the woman to my left all felt like we couldn’t breathe. Our throats filled with acid. Tears were running down our cheeks. And we were all coughing. We didn’t know each other but we felt as if we were being gassed. The poet’s photograph was of a relative who had been killed in Auschwitz. I ended up thinking, no, couldn’t be, yeah, it could be, no, it couldn’t. But, yeah. it could. Why not be open to it?

JENNINGS

In Three for the Road, all three protagonists leave their current homes in hopes of finding new lives or because they feel like they have no other options, and in The Home for Unwed Husbands Kay is changed by her trip to Greece. Why are you drawn to this type of story arc?

GILES

I don’t know; when it comes to fight or flight, I flee. Don’t you think it’s so much more fun to just get out of there? I’m horrified in my own stories to see how many of them end with someone in a car getting the hell out. I don’t know what’s wrong with me. I want to pinpoint it before some critic comes in and says, “Hey, she uses a lot of cars.” I adore the end of Huck Finn. Lighting out for the territory? What could be better?

ANDERSON

Just for fun, what’s on your writing desk when you do get down to business and find the time to write? And are there any tools or habits you feel you can’t write without?

GILES

I used to smoke. I’m so glad I quit, but I used to think that if I did, I wouldn’t be able to write. Then I found that I wrote just as badly when I wasn’t smoking as when I had and it was a relief. It’s amazing how when you come to a part in your story that’s really going to open it up or push it forward, you suddenly wonder if there’s anything in the refrigerator. Or you have to pee. There’s some instinct that makes you push back from the computer just when you’re about to nail it. I’m restless. I get up and come back and get up again. One thing that’s always in my writing room is a couch. I like to crash, and sometimes just meditating or dosing your eyes for a few minutes will help refocus you. I also have a little green Buddha on the desk. So how about you? Do you have any superstitions?

SINGH

It’s not my habit, but I was listening to a podcast with Ocean Vuong. He apparently wears boots every single time he writes.

GILES

That’s interesting. I love Isabel Allende’s process. She starts a new novel on the Epiphany, January 6th, every year. Bharati Mukherjee, who grew up in a crowded house in Calcutta, kept a TV blaring in every room when she moved to Berkeley. We all have different needs. I like having a crossword puzzle book when I get stuck, especially one with the answers in the back.

BUCKINGHAM

The title story in Rough Translations is about a dying woman. Did she have anything to do with the creation of Ida?

GILES

No. She was just a dearly loved friend. Ida was loosely based on my mother. Have any of you tried to write about your mother? The first story that I published was “Old Souls,” from Rough Translations. It came out in a magazine at that time called Playgirl. It had a naked man in the centerfold. You couldn’t get it at the regular magazine stand. You had to ask for it. My story was sandwiched in between ads for something called Sta-Hard Cream that looked like Elmer’s glue. I wanted to show this story to my mother because I was proud of it, and it had been published, so xeroxed it and cut it out column by column between the ads, but I worried she would recognize herself as one of the characters. She read the story, and then she looked up all starry-eyed and said, “Darling? Who’s the bitch?” “Diane’s mother,” I peeped, and she nodded and said, “I thought so.” So that was my first published story, and it was an introduction to shame. I don’t think dignity is a word that writers can claim. We submit. When your work does come out, you can be proud for the moment. But if you’re in a magazine, you may be read on a toilet and thrown away. You just learn to walk tall. And wear boots! No wonder Ocean Vuong wears boots. Good idea. These boots were made for writing, and that’s just what I’ll do .