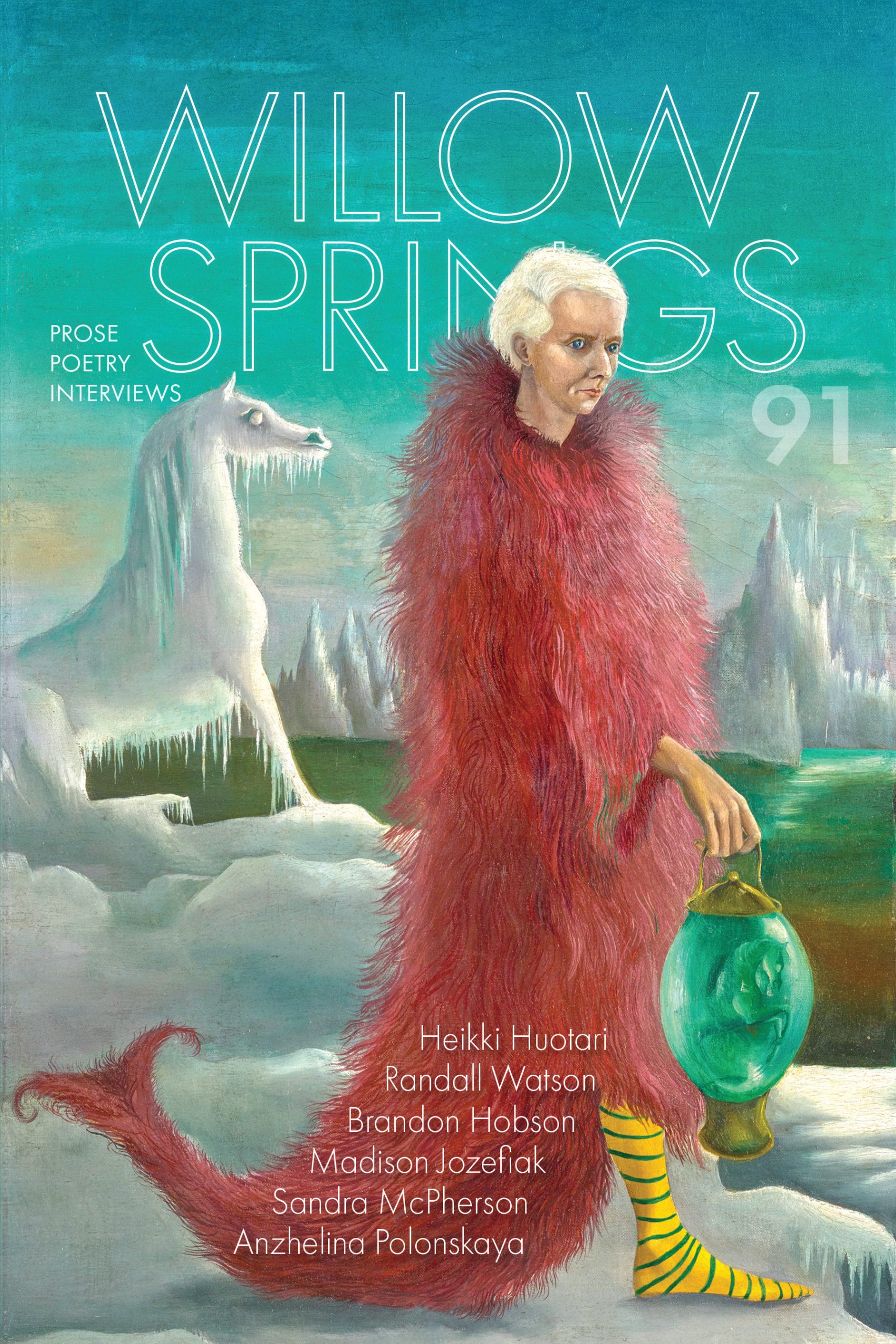

About Lis Sanchez

Lis Sanchez is a grateful North Carolina Arts Council Fellowship recipient. Her poetry may be found in Michigan Quarterly Review, The Georgia Review, Ploughshares, Cincinnati Review, The Bark, and Copper Nickel. She has received Prairie Schooner’s Virginia Faulkner Award for Excellence in Writing, Nimrod’s Editors’ Choice Award, and The Greensboro Review Award for Fiction. Her most cherished people are her husband and her plott hound.

A Profile of the Author

Notes on “Seaquake”

In 1899, Hurricane San Ciriaco pounded the island of Puerto Rico with a brutality never recorded there. Thousands of people drowned. My great grandparents, like so many Boricuas, not only lost their home but their means of livelihood. The coffee plantations and agricultural industry were all but destroyed, the distribution of relief food depended on the pleasure of new U.S. corporate overlords, and the bodies of those who had starved to death appeared on the roadsides.

Music, Food, Booze, Tattoos, Kittens, etc.

During the first year of the pandemic, I lived in a tent in my backyard. I had to. Like many people with environmental illness, I’d learned that my home was unsafe for me.

While outdoors, I listened. The backyard, while within the city limits, sloped down to a wooded ravine with a creek running through it. Nights, animals came to slake their thirst. They wandered around my tent. Cocooned in my small space, I heard footfalls, soft or loud, disconcerting at first.

Frequently, barred owls jarred me awake with fervent calls. Not those “who cooks for you” suavities—these were gruesome cacophonies—gargles, snorts and hisses, horrors my imagination mistook for creatures tearing the heart from other creatures.

Eventually I came to recognize the sound of deer moving through leaves. Of possums scaling the wooden fence and flying squirrels latching onto a poplar. I could distinguish fox from cat or coyote. I welcomed the sounds of their movement and wondered at my good fortune.

I heard human sounds too. At two a.m. I was wakened by a vehicle screeching to a halt. A man hollered from the street, “You wanna know what matters to me?” Seconds passed. The car door slammed. The engine roared down the street, then it hushed while the lone voice shouted curses at the sleeping houses. Next day, neighbors posted online that their Black Lives Matter yard signs had disappeared.

Weekends, my neighbors across the ravine blasted golden oldies from their patio, shaking the walls of my little space. My blood boiled: were these the Covid parties I’d heard about, intended to hurry the spread of the pandemic? By midnight, bouts of laughter gave way to shouting and delirious howling. I remember lying alone in the dark, wondering what it took to abandon oneself so completely.