MARCH 30, 2017

ALIA BALES; CASSANDRA BRUNER & CODY SMITH

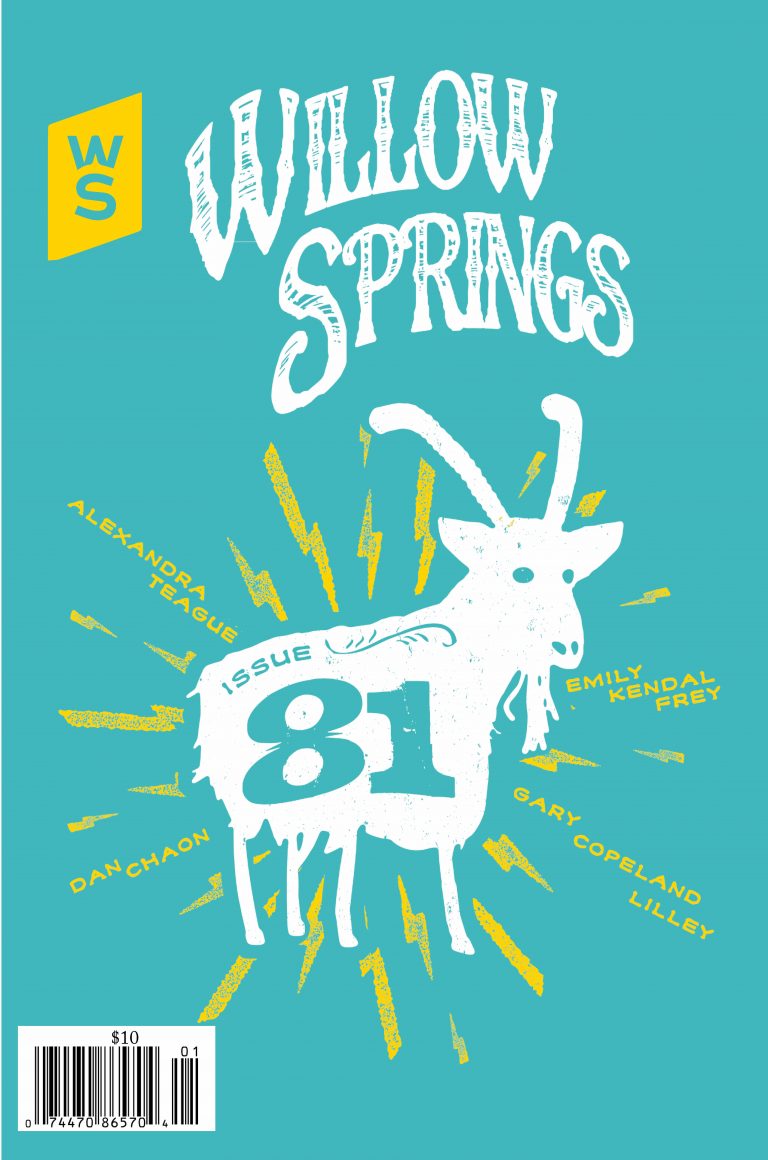

A CONVERSATION WITH GARY COPELAND LILLEY

Photo: centrum.org

THROUGH HIS CONTROL of persona and voice, Gary Copeland Lilley examines the experiences of people often relegated to the margins—sex workers, prisoners, drifters. The undercurrent unifying these characters and voices is Lilley’s innately felt musicality, drawn from the litanies of the King James Bible, the looseness of the blues, and the recitation of hoodoo ritual. A deep lyricism suffuses his poetry. In a review of Alpha Zulu (Ausable Press, 2008) for The Believer, Stephen Burt writes, “Without such stories there would be no poems, but no good poem is only a story, and Lilley’s power comes from his sound: syncopated, densely compacted, defiantly resigned.”

Gary Copeland Lilley is the author of four books of poetry, most recently The Bushman’s Medicine Show (Lost Horse Press, 2017) and High Water Everywhere (Willow Books, 2013), as well as three chapbooks, including Cape Fear (Q Ave Press, 2012) and Black Poem (Hollyridge Press, 2005). He’s received the DC Commission on the Arts Fellowship for Poetry twice, in 1996 and 2000, and earned his MFA in Poetry from Warren Wilson College in 2002. A founding member of the Black Rooster Collective, he is also a Cave Canem fellow.

Originally from North Carolina, Lilley was a longtime resident of Washington, DC, served a stint as a Navy submariner, and currently resides in Port Orchard, Washington. His breadth of travel informs his work, as place and geography act as a singularity around which his personas form. To read his poetry is to engage with often-overlooked voices, with haunted and defiant landscapes. Lilley’s poems are powerful vehicles of empathy, relaying autobiographical, historical, and folkloric memories with precision and compassion. We met with him in mid-spring in Spokane for the release of the Bushman’s Medicine Show, where we talked about the risks of persona, the Wilmington massacre of 1898, and the balance of craft and politics in writing.

CODY SMITH

There seem to be two competing schools of thought in contemporary literature. One is that you need to have a life full of experience, which you’ve had—you were in the navy, a member of the Black Panther Party, and have lived many different places. The other school says you need extended time in academia. You’ve had both. Are those two worlds harmonious?

GARY COPELAND LILLEY

I’ve been a lot of things. I was in a band. I was a submarine sailor. I was in the Black Panthers. Sometimes people look at me and say, “How can you do that—both the submarines and the Panthers?” I believe in the right to dissent, but my family has always had people in the military. Me and my cousin are the only ones from our generation. He was Army, I was Navy, but we went for the same reason. We believe in freedom, that we have a document that guarantees that. So yes, these things are compatible to me because I have lived all these lives.

When I got the Joan Beebe Teaching Fellowship, to go back to Warren Wilson College and teach in the undergraduate program, one of my friends said, “Gary, I don’t know if you can handle the politics.” I’m thinking, politics? Of course I can. But I didn’t know about those kind of politics. That’s what gets me in the academic world—people are so protective of their space, competitive. They’ll undermine you and cut your throat for that tenure.

There’s always someone who doesn’t like the way you’re doing things. You’re moving too fast. “He wears leather. Did you know he listens to hip hop in his class?” You said we can design our own composition class? Mine is based on Hip Hop America by Nelson George. We’ll read it, discuss it, play the music he talks about. Okay, now you don’t like it because I wear Timberlands while I’m doing that. Really?

And then, lo and behold, I know what the real problem is: I’m the only black faculty member there, and they didn’t know I was coming. Because I won the Beebe, they had no choice. That’s chosen by the MFA program. So when I showed up, I’m like, why are they on my shit? I didn’t understand what my friend meant when he said, “You aren’t gonna like the politics.” All this jockeying for position. And this is the trip—I love teaching; I just don’t like what comes with it.

CASSANDRA BRUNER

Your work often deals with racialized experiences in different parts of the United States: North Carolina, Louisiana, the Pacific Northwest. In these places, and in your poems, there are ghosts—historical figures and phenomena often overlooked by society at large. Would you talk about this in the context of your work?

LILLEY

I grew up around the area where some of John Brown’s Raiders came from. So I’m always close to that. My family is connected with that whole movement. There are all these stories, and you can see how just one thought of freedom—just one thing—blossoms. But I’m not about making a manifesto, I’m just trying to write a poem or a story.

That’s where I differ from the Black Arts Movement. Their whole thing is that the poetry is subordinate to the politics. My feeling is that poetry can never—art can never—be subordinate to anything. If you’re going to use art, why is it subordinate? If you make art, make art. If you want to write a manifesto, you can do that.

The art in Larry Neal’s Hoodoo Hollerin’ Bebop Ghosts is not subordinate to anything. The message is in it, but it’s not the type of poetry that people typically want to see from the Black Arts Movement. That aesthetic comes from Larry Neal and Amiri Baraka. We know Baraka because he lived. Larry Neal died in his forties, so we don’t know Larry Neal, though he was the main architect of the Black Arts Movement. They wanted music to be represented in how they write—something Langston Hughes did too, when he was doing the blues. No one did that before that generation of African American writers. But when Langston goes there, he goes in the twelve-bar blues form. When Sterling Brown goes there, he goes with work songs, like his poem “Southern Road.”

Langston’s first poem is the poem I think he chased his entire career—”The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” That poem’s a killer, and to be your first. Damn. What heartache, over and over and over. In the end he started stripping all the music and everything out of his poems because people were misinterpreting them. I feel compelled to keep that kind of stuff in. I’m not anything without music. It’s been such a big part of my life. To me, Langston was removing the art.

Look at his last book. That’s where he makes everything crystal clear—”This is where I stand politically.” I don’t want to be that.

ALIA BALES

What do you want to do instead?

LILLEY

A bunch of us started writing in DC, the Black Rooster Collective. It was four poets and we wrote our own aesthetic, what we were personally looking for, because we were horrified by what had happened to Langston. People were not understanding, were always trying to define what he was trying to do. We said, “Well, let’s just remove that barrier right now. Let’s tell people what we’re trying to do. Individually, what we’re trying to do.”

We started from this visual artist, Renée Stout, who said she was getting more inspiration from the poets in town than the visual artists. She was coming to all the poetry readings and open mics and she picked four of us who she wanted to workshop in her studio.

We walked in and the first thing we saw was this huge painting of a black rooster. Everybody gets the wrong idea—”Yeah, four black male poets call themselves Black Rooster.” No! We would talk to each other like, “Meet you at the Rooster Monday night,” and people would be like, “The Black Roosters, that’s who they are.” I mean, when you walk through her door, it’s the first thing you see.

She wanted a company of poets around her, so she started this workshop, and we would meet every week, for five or six hours. We’d cook food, then have discussions about what was going on in the political world, what was going on in the art world, and then it was just random street gossip, all of which became the basis for that work. We’re singing the street that we live on . . . this is our street, the politics and everything that’s happening, being represented on that street. We see what’s going on, and that’s driving us, but how do we take this world onto the page? We had the Black Arts Movement, we

had Larry Neal, Amiri Baraka.

Baraka’s first book just killed me, Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note. People ask, “What happened later?” He just got angrier and angrier. No more beauty, just rant. I was glad to see him a few years ago, just before he passed, in a teaching mode, working with younger writers. He’s this elder, and there’s a total change in him. Now he is really kind of connecting to us and trying to teach us and make us feel welcome . . . but that was not him in the day.

It’s like you listen to the blues long enough and you can tell these guys’ lineage. Mississippi Fred McDowell in the hill country—and Junior Kimbrough and R. L. Burnside, you know, are a branch of that family. You have Otha Turner and Jessie Mae Hemphill. Then you start seeing the people who come off of that tree of musicians. Literature is like that too, especially poetry. You have people who have worked with people, people who come from the same places, and you can see where this is the trunk and these are the branches.

After I read Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note, I wrote like LeRoi Jones for six months. I wanted to be him. Something he does resonates with me, grabs me. Then it was Baldwin. The start of it, though, was Gwendolyn Brooks. In that little poem, “We Real Cool.”

Me and my friends walked into a headshop back in the day, and there was a black light poster that had that poem on it. We learned it right then, the entire poem, because we thought she was talking to us. We’re at this age, and we’re rebellious, and it speaks to who we are. She got us. That’s it, man, that’s our poem. So we’d see each other in school, “Hey, man, what’s up?” “We real cool.” We’d just bounce lines.

I’m teaching some high schoolers, and they, the hip hop boys, are all into that poem. They all felt the same way we did. It’s not fatalistic. It’s defiance. When I met Ms. Brooks, I told her the impact of her poem on me: “And now I’m teaching and I’m seeing the impact of your poem on this generation.” And she says, “Really?” And I said, “Yeah. It was just like this fighting thing.” She said, “They feel like that too? I wrote it as a dirge.” And I said, “That’s not the way we do it!” I’m serious, I went there—”that’s not the way we do it.” I mean everyone who does that poem, no one is thinking this is something sorrowful.

The hip hop boys were reading it the same way I was reading it. We thought the poem was for our time of rebellion, and they can think it’s for their time of rebellion. That’s the impact. What comes through is defiance, look at the way she wrote the lines. Why does it start every sentence with “We” but the “We” is falling on the last word of that line? That moment of inflection. That’s where you see it. “We/Left school. We/Real cool.” It’s like that, you know? “We/Lurk late. We/Strike straight.” She breaks that line. That’s some bad stuff, man.

I didn’t know a poem could do that, could make you feel that—until then. All four of us standing there looking like . . . might as well have been Moses walking down the mountain with that poem. For us, as teenagers in a time of rebellion, we’re seeing everything happen—the war, all sorts of racial stuff, and everything is going against us—then there’s this poem. It gave us some steel. You know, that inflection, the little things you pick up. I see the power of that and I know what it did for me. I want to make that effect, too.

BALES

Can you say more about how you find poets you love and try to inhabit their voices?

LILLEY

With Baraka, LeRoi Jones, I did that for six months. When I started doing Langston, and hearing Langston do the blues, I was like, well Langston’s writing the blues, but this leads all the way back to the mother country.

I used to get criticized as a young poet by other African American poets. They were like “Where are you coming from?” They said, “It’s hard for me to find the word ‘black’ in any of your work.”

Do you doubt the person speaking is black? I wrote a poem called “Black Poem.” I mean, that was it. That’s in response to not having a poem that said the word “black.” It doesn’t have to, but since you want one, you know, here’s “Black Poem.”

This was before the MFA. I was a student, but I couldn’t believe I was being criticized—you’re questioning my ethnicity from the page or something? You’re not picking up enough correlatives there? I mean, do you need me to say for sure that I’m black? So my issue then was, how come they didn’t pick it up?

But I don’t feel like I need to raise that flag every time, to say, “This is who I am.” Who I am is already there. I try to follow something Walter Malty said—that every day he sits down to write, he puts the truth about himself into that work.

BALES

You’ve lived in many places. Does where you’re living effect how you’re writing?

LILLEY

It does, but it doesn’t effect the main aesthetic—what I wrote with the Roosters long ago. I believe that fifteen percent of African American people speak nothing but standard English, and another fifteen percent speak nothing but what we have come to call Ebonics. I work that other seventy percent—on both sides. I want my work to reflect where I’m from. I want my work to have that music in it. And that’s a simple thing, aesthetic.

When I move from place to place, the main aesthetic stays the same, but the specifics change. I couldn’t write “High Water Everywhere,” or any of the stuff about New Orleans until I was in the Pacific Northwest. I had to have distance.

Writing about North Carolina, which I think is probably one of the most beautiful states and also one of the most oppressive, is tough. I never understood why my family was so worried when I would fight Klansmen’s sons when they said something to me, or did something I thought was disrespectful. I had come from New York. Dude, I’m not taking this. It took me a long while to figure out that my family knew what happens—they were born and raised in North Carolina. They knew people who were dragged out of their homes. They knew that retribution would be paid for putting your hands on one of those Klansmen’s sons. It took me a while to get the optic on, like, what’s wrong with my people? And then I figured out later—oh, it’s about safety. The sheriff is thirty miles away, and he’s probably a Klansman too. There will be no calls responded to here.

To write Cape Fear about the Wilmington Massacre and everything? I studied that after I discovered it up in Province town reading the paper—”The New York Times apologizes for their part in the Wilmington Massacre of 1898.” You know one of those little articles. Whoa, Cape Fear is sixty miles from where I lived. I had never heard of it. None of the black people in my county or any where around there ever speak of it. How can a massacre happen and we not hear about it? A massacre of African American people. And why is the Times apologizing? I researched for a year or two before I could start to write those poems. I got down to Wilmington; you know what I didn’t find? Tombstones that had any correlating dates or anything close to it. It’s like, this is how we censor you.

The blacks are saying there were over 2,000 people murdered. The whites are saying twenty. Those white families are people who became our governors and congressmen for the next sixty-something years. They shaped everything. They shaped what’s taught in the schools.

North Carolina history is required. How come I don’t know about the Wilmington Massacre? The research has shown me this: there had been a white party, small farmers who felt like they were being victimized by the industrialists of the time. They couldn’t ship their crops because they were being charged too much. You have the blacks who are into the Reconstruction. They are the most upwardly driven people the white farmers have ever seen. They’re in Wilmington, the biggest city in North Carolina at that time. 25,000 people. 17,000 African Americans. Those white small farmers joined with them to create the Diffusion Party. The election of 1896 rolls up, they win every available seat. And that’s when the conspiracy starts, from the old Confederates, to restore the order. By the next election, 1898, if they don’t elect us again, we’ll take it from them. That’s what went down. They murdered a bunch of people. So how come we don’t know this stuff? You look at North Carolina now—that kind of repression and silencing was allowed to go on. It put us in the political shape we’re in today, changed the trajectory of everything.

Now we’re in this spot where they can pass a stupid-ass bathroom bill and lose billions of dollars over it. It’s not about the bathroom. They have a provision in that bill that makes it impossible to file against discrimination. They want that—that you can’t legally challenge discrimination. It’s not, “We want people to go to the bathroom of their natural gender.” That’s not the bill. That’s the fight the rest of the country sees. The real fight is about retaining the legal right to file against discrimination. To have a legal recourse against discrimination. They want to take it away.

The same stuff made my parents fearful of me fighting Klansmen’s sons. They knew what could happen. I didn’t. Now, do I think my parents knew about the Wilmington Massacre? Oh, yeah. How could you not? Word travels. If they’re killing your kind, you better believe word travels. They knew. So I write stuff like that just to counter the effect of the silence. We need to talk honestly. I understand the change the whites in Wilmington were going through. But here’s the funny thing. For people who have always had privilege, equality is oppression. That’s how they saw it. How they’re seeing it today.

BALES

How did your activism as a member of the Black Panther Party influence your work?

LILLEY

A lot of the people I knew around the Panthers were also solidly into the Black Arts Movement. The Panthers started in ’66, the Black Arts Movement started, I believe, a couple years later. Everything was in support of their activism. But I was a writer when I joined, you know. So that wasn’t an issue to me. Is art second, here? No, it’s not. I was a writer who joined the Panthers, so I’m not shifting. I did write political articles, but that was different than my creative work.

As far as activism, I also went to the William Joiner Center for the Study of War and Social Consequences in the 1990s. It’s a center for Poetry of Witness. That’s activist writers—Carolyn Forche, Yusef Komunyakaa, Tim O’Brien, Bruce Weigl, Fred Marchant, and on and on. Poetry of Witness. That’s what they all came together for after the Vietnam War. I was there about the time Carolyn did that anthology, Against Forgetting. I had read The Country Between Us and “The Colonel,” that poem of Forché’s that everybody goes to, but to me it’s the whole book.

Tell me that’s not art. There’s something political about “The Colonel,” yes. He’s got a bag of fucking ears, you know, that he has taken from people. She starts off, “What you have heard is true.” And she’s there with the friend and his eyes that say: “say nothing.” We can read newspapers for the facts, or the alleged facts. But art has such a bigger impact. This is a character who is sitting in the presence of someone who has a bag of ears. He takes one of them, drops it into a glass of water, and it comes alive. The others, he sweeps to the floor. “Something for your poetry, no?” And “Some of the ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.” Killer lines.

I’m still an activist. I participate in many things. Writers Resist? That was great. Everyone just puts that stuff out there and the next day, the next day there’s all these people setting up readings. Yes, I’m down. And what was it about? Freedoms, baseline equality. Why can’t equality be a baseline? My activism pulled me into other things in the community. It’s about making change. At the same time, in my work itself, I’m not going to be lobbying for those politics. I will show you something about that world though. I will show you a character from that world. I hope people don’t necessarily think that’s me, though, because I wrote serial killers too.

BALES

With poems that aren’t clearly delineated as “persona,” people do often read them as autobiographical—

LILLEY

I made the mistake of reading that serial killer poem at a reading—didn’t sell one damn book. I knew I was in trouble when the publisher started explaining, “He’s not like that … “

There was a person in DC when I was living there killing women and stashing them in the ‘hood. But DC doesn’t want to call attention to serial killers walking their touristy streets. Around victim seven, I started writing the serial killer, would read it at open mics. Because I had already kind of got this inkling, like, maybe this is someone who can walk in my community undetected.

I was pissed off about everybody in the black community knowing that something is happening, and nothing seems to be coming from the administration, nothing seems to be coming from the police about it. They’re just finding bodies and saying, “Well, separate incidents; this is the murder capital.” But it was a serial killer. I figured it’s somebody who can walk around, who knows the drug territory. I had to bring that to attention. That’s the risk of persona, that people associate the speaker of the poem with the poet.

With my poem “American Rapture at 13 Degrees,” people are like, “That was such a great poem about you and your son going to that football game.” I don’t have any children. I wrote that watching a game on TV. I saw this black man and his son, they’ve got end-zone seats, and just the way he looked at the boy when the player gave him the ball after scoring a touchdown, I was like, that’s enough for me. It was a play off game in Chicago—cold as shit—and I’m watching this and it was clear to me that they weren’t people who were well off. This guy in his seat is just as happy as this boy. Right after the game, I started my first draft of that poem. I don’t know them, but I have to make the character work somewhere. And I do know people who work at businesses as cleaning people who are given tickets for games. So I put those two together. That’s what I’m talking about—truths mean more than facts.

SMITH

When starting a poem, do you hear its voice or see its images first?

LILLEY

I start with sound first. I don’t have line breaks when I start. It’s just a free flow of writing that takes me all the way through. Then I have a score. The next stage is the images. But I’m from the South, so territory and location are important to me. Sound helps me locate the poem. It defines the space I’m in, the territory. I start looking at the natural things first. Even if I’m writing from an urban area, from an urban space, an urban poem, it will be the broken glass in the street, and how it looks . . . the street lights look like semiprecious gems, something like that, because I’m always called to the territory I’m in. One of the main pillars of the Black Arts Movement was the language of the poem as reflective of the music in our community. Southerners have a way of talking that’s musical. There’s a musical quality in language itself, a musical quality in all of us speaking, that we don’t normally look at.

This is one of the hardest things to teach students. They’ll be writing a poem, and all of a sudden, they have a different idea of what language is because I’ve said we’re going to write a poem. And they start thinking about the language, the lines, the this, the that. Okay. So we’re not going to do any line breaks. You have to bring to them the idea that we can write the way we talk. Create the voice you hear. A lot of times, people assume that what you’re talking about is the authorial voice. No, that’s the aesthetic, the style. But the voice is the voice that actually comes off that page, the character’s speech that you hear. And you can make that as distinct as you want. That’s where the poem is located.

I have to make sure people understand where we are. And if I know some of the natural things that are around, it’s easier to build images with them. The diction is also going to show social status, the economics of the person speaking. I want to understand syntax, to make that dialect without inventive spellings. I want to use the English spelling and just invert the syntax enough to where people can hear a voice from a particular region, a particular social class, use the syntax to do that, and still have that ear for music, to make the music happen.

BALES

In your first book, you have a glossary of terms, but not in your later books. Why?

LILLEY

In the first book, the publisher was like, “Nobody understands this. What do these things mean?” My readers have a responsibility too. For my first one, I was like, well maybe they won’t understand what these hoodoo terms are and what they mean. And even though I’ve continued to use those references in other books, I don’t provide definitions now.

I hope my work makes readers curious enough to satisfy that itch, to go after it themselves. I want to lead them there. I don’t want to drop them into a dark room with no light. In the context of the work, I think there are enough clues for you to find out, especially if I’m talking about the gods. If I’ve got a girl dancing in the strip club, wearing certain colors, and there’s a series of fives—maybe she has five rings on or something like that—that’s a representation of an orisha. The people who are into that automatically know it. And for people who aren’t, it’s just a nice image with this woman wearing five rings, and they still make note of it. But people who are into the Yoruba or any of the old African religions, they know these representations without me saying it. I figured that out after the first book.

I still want to write the good poem, the good piece, that keeps others interested too, and hopefully they will be curious enough to ask, “What is this about?” That’s their responsibility. Mine is to lead them there, and to have clarity. That’s hard enough.

BRUNER

What role does the blend between Christianity and hoodoo practice play in your work?

LILLEY

They mingle in any Southern territory. You find the people who are devout. They are very much aware of the conjure; they are aware of the hoodoo, and the people in their community that practice. These are the same people sitting in church. It’s not like there’s a distinct school of this and a distinct school of that. You have both sides, but there’s ground in between, which is where most people are.

My family is devout Christian, and I’m probably the last serious convert to Christianity they had. But everyone is like, “He’s into this other thing.” You know, they wouldn’t even mention it. “He’s into this other thing.” But my mom would come to me and say like, “This is happening to me, over and over. Somebody has targeted me. Do you know anybody that can make this better?” That’s how she’d ask. I’m not supposed to say, “Yeah! You can go see the conjure.” No—it’s, “Do you know anybody that can make this better?” And that means I’ve got to handle this for her. I know who to go to. But at the same time, she’s praying and doing all this other stuff.

SMITH

I’m interested in how your poems, especially in The Bushman’s Medicine Show, seem to jettison much of organized religion, with the exception of the music. They set out a sort of reclamation of the profane and the holy. Can you speak about that tension between backslider and saint?

LILLEY

The whole thing’s about religion. When I was younger, it was a problem for me that my family was such a Christian family, because I came up in a time when we were investigating everything that allowed slavery to happen. And the Christian church, of course, was a part of that. The blessings of the slave boats, the investment of the North into shipping. When slaves arrived on the plantation they were stripped of their own religion and made to be Christians. They weren’t allowed to even say the names of their gods, or play any of their rhythms in worship. Except in one place—New Orleans. That’s why there’s such a presence of voodoo there. Slaves were allowed to go to Congo Square to worship and play their dances. They were allowed to say those gods’ names. That wasn’t the case anywhere else in the South. They’d get severely punished for that. The Christian Bible became the way slave masters controlled slaves. So I had this big problem with Christianity. I did my investigation of all these different religions and then decided that religion was the problem.

Imagine a room that has eight, nine, ten doors. Each is a religion. People will open a particular door and stand in the doorway. But if you walk into the room, that’s where you find spirituality. To me, all those were the same.

My brother was a minister for twenty-eight years, and we talk about this all the time. You see the beats that they do in the Pentecostal church, they’re doing them on their bodies and stuff? That’s the same beats they play on drums. And the state of possession that y’all call the Holy Ghost? Yeah, we call it state of possession, period. I mean, really. But it’s those gods that would enter the space. We believe they are represented in ordinary people, that the presence is there, all the time. You won’t necessarily know, but you start to recognize different people you meet, some facet. And there is this duality. It felt more free to me. It felt more true, honest. That approach made Christianity accessible to me.

And the music? It’s a natural fit. There’s a sacred blues and a secular blues. This whole nature of how blues came about—people like W.C. Handy “discovering” the blues, “creating” the blues. 1910, that’s when he wrote it down. He was the first person to do notation for it, but it comes from way back. Way back. When Africans were exposed to the Bible by the plantation owners and masters, they weren’t allowed inside the church. But they could stand outside and listen through the windows. And they were given the same hymnal.

That’s why you see those old church songs from black people—the sacred blues. The secular blues is stuff played when people are drinking, dancing, trying to get it on. But it’s the same basis for the music. You look at so many old blues players, like Son House, a child evangelist who got in trouble, went to jail. It was over a woman. But he comes out, and that’s the thing, that’s the tension within him. What is the secular and sacred? He was always at battle with that. You could go listen to Son House back in the day and he’d start off in the juke joint on Saturday night, playing those drinking and blues songs, and the drunks that passed out in the place would wake up Sunday morning and he’d still be playing. Only now he’s doing gospel. It’s the same music. Church people tried to change it around, to use different chords. But those blues guys, they play church songs too. I came up hearing all that stuff and hearing it both ways.

I kind of lean towards the blues guys. Church people like G, C, and D chords. It sounds so melodic, softer and beautiful. But the blues guys would play those songs and they’re doing E, A, and B, you know, or D, G, A. They’re doing stuff that churches don’t normally do because of the sounds. Church people will run you away for playing those tones. When I grew up, you were not allowed to bring an instrument into the church except for a piano or an organ. You couldn’t even bring a guitar. Now you go into those churches, the drum kit is set up. They’ve got the bass and guitar, a keyboard. That’s the freedom of the music, but it took a long while to get there, except for the people who played the blues. They played it, period. They still play it. They play it better.

It was a big thing, because I played guitar. When I went home to take care of my mom, I dropped out of sight for about two and a half years to take care of her. But I came home with guitars. I was her fallen son at that time, and she walked into the house and I’m playing blues. It was a quick switch then to the church songs. If I wanted to play guitar in the house, I’d have to play something like, “What a Friend We Have in Jesus.”

BALES

Your work is in conversation with a long oral history. What do you think is the difference between poetry read aloud and poetry on the page?

LILLEY

None. I mean, really. Patricia Smith won the first four national slams. She was part of the Green Mill team from Chicago. But she was slamming the same poems that are in her first two books, her first book especially. She’s winning with those. She erased the barrier between stage and page.

People used to argue that the barrier existed. There was a hierarchy. The page writers were the ones deemed to be literature, and I was like, this is some apartheid shit going down. This is literature, you know. When I started my MFA, the word was, “Oh, he’s a street poet.” And we do read on the streets, we read in the bars, we do all that, but we write them too. And read them. Stage or page, what you want to do is have a poem that has sonic quality. You want to hear it. I get amazed at people who write poems and don’t read them while they’re writing and drafting and revising. If you do that constantly you start to pick up the hard sounds, start to pick up on the rhythm.

Then you’re like, why is that rhythm off? Oh wait a minute. I need to check out the Handbook of Poetic Forms. And you look at it . . . ah, it’s the combination of that anapest and that dactyl. Once I become aware of that, then I see how the different combinations of sounds work or don’t. It’s not like you sit down and say, I’m going to write a line that has two spondees. You write and say: Why’s that line grab so hard? What did I just come up with that gives it that quality? You don’t sit down with a formula, but once you get it, you start to recognize it. It’s like playing music. You become aware of the riffs that are available, and it’s like you have choices of words to make the tune fit. You start to feel the effects of how changes in rhythms work. I know spondees are propulsive. So if I want to run them together, boom boom, that’s the sound. They’re both accented, those syllables, and it’s that propulsive thing you get. I had a teacher once who was trying to explain to a class what a double spondee was, and the kids said, “What’s a double spondee?” And the teacher said, “Fuck you, asshole!”

You will never forget then that these are accented syllables. You’re creating that effect on the line—where you break a line if you choose to use line breaks. And you can use that line break to frame music, to frame image. To try to keep it intact as long you can, and then to break it so it has tension. If I’m enjambing, I know that it’ll pull down—it’s going to put a moment in there. Not a stop, not a soft spot even, just a moment, what Dana Levin calls “the space where you can also create inflection.” It’s in how you run that line, how you run that sentence down.