July 16, 2014

JEFF COREY, KRISTEN GOTCH, AILEEN KEOWN VAUX

A CONVERSATION WITH KIM ADDONIZIO

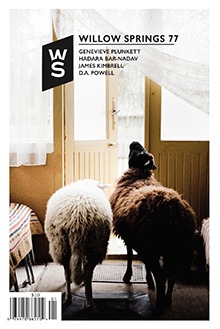

Photo Credit: Trane Devore

…I’m saying

in the beginning was the word

and it was good, it meant one human

entering another and it’s still

what I love, the word made

flesh. Fuck me, I say to the one

whose lovely body I want close,

and as we fuck I know it’s holy,

a psalm, a hymn, a hammer

ringing down on an anvil,

forging a whole new world.

These lines co me from Kim Addonizio’s poem ” Fuck” from her fifth collection of poems, What Is This Thing Called Love. It is for moments like these that Addonizio was referred to by Steve Kowit as “one of the nation’s most provocative and edgy poets.” Yet provocative and edgy seem like surface examinations of a body of work that is deeply beautiful and supremely intelligent. Her poems are honest reflections of human experience, instinctive and electric—like a first kiss, a first touch—the word made flesh.

Kim Addonizio was born in Washington, D.C. in 1954 to tennis champion Pauline Betz and acclaimed sportswriter Bob Addie. Although she was raised in a family of athletes, Addonizio herself was never interested in sports. In her essay “For My Mother, One Last Grand Slam,” recently published in the New York Times, Addonizio writes, “I used to have a really snotty attitude toward sports, convinced that they were trivial compared with Art, but that was when I was young and ignorant. Now I know better. Now I understand the importance of the body.” Indeed, her honest depictions of the body compel us to her work. Throughout her writing she examines the body, boldly facing its most intimate details—the long vein rising up along the underside of his cock… the strawberry mole on his left cheek—facing how it succumbs to age—curled yellow toenails and a belly as milky as the swirls of soap.

Addonizio is the author of collections of poetry and short stories, as well as two novels and two books on writing, one of which, The Poet’s Companion, she co-authored with Dorianne Laux. She has earned numerous awards for her work, including Guggenheim Foundation and NEA fellowships, Pushcart Prizes for both poetry and nonfiction, and a John Ciardi Lifetime Achievement Award. Her poetry collection Tell Me (2000) was a finalist for the National Book Award. At the time of this interview, Addonizio was anticipating the release of her latest collection of stories, The Palace of Illusions, including the story “Intuition,” which first appeared in Willow Springs 74.

An accomplished blues harmonica player, Addonizio often incorporates music into her public readings. In fact, much of her poetry is tied to American blues. Her most recent release, My Black Angel, is a collaborative collection of her blues poetry alongside woodcuts of blues musicians by artist Charles D. Jones. Of this collection, singer songwriter Lucinda Williams wrote, “I don’t just hear the blues in these poems. I see the blues inthese poems. I see myself in these poems.” Addonizio is drawn to the intimacy of the blues, what she describes as “one consciousness speaking to another about what is really true for them,” and she sees her poems as part of an ongoing conversation with these traditions and musicians. “It is a call and response,” she says, “a way to be part of the same song.”

Addonizio teaches creative writing classes privately and spends most of her time between New York City and the San Francisco Bay Area. We met up with her at the Port Townsend Writers’ Conference last year, where she taught a blues and poetry class with Gary Copeland Lilley. On a summer afternoon, we discussed blues, sex, the life of the artist, and pushing boundaries.

KRISTIN GOTCH

In the introduction to My Black Angel, you mention growing up with bands like Led Zeppelin and the Stones, and then coming to the blues after that, which felt like coming home. How did the blues feel like coming home?

KIM ADDONIZIO

Because I had those chord progressions in my head already, by listening to rock ‘n’ roll and the blues of Paul Butterfield. A lot of those musicians were responsible for some of the revival of interest in early blues figures who had faded into obscurity. They brought some of them back to perform for audiences, and they kind of had a second career later on.

What turned me on to blues harmonica was Sonny Boy Williamson—it was like being struck by lightning, which was the same way poetry hit me. When I heard Sonny Boy Williamson play, I sat up and took notice, and that’s when I began to get interested in the blues and blues harmonica. I was into Chicago blues first and then I learned a lot about early country blues from another harmonica player who was into the Delta stuff. I started going to music workshops, which are a lot like writers’ conferences, except that you have harmonica players wailing away and making strange sounds.

GOTCH

In What Is This Thing Called Love, you open with a Willie Dixon quote: “The blues are the true facts of life….” How so?

ADDONIZIO

There’s something primal about the blues, so much about feeling first. That’s what speaks to me. The language of the blues hits on those primal subjects—love and loss and getting through hard times. There’s also a subversive element that Gary Lilley was talking about in class, the way those songs are about struggle. So you can take it to the political level, but it is also personal. The blues singer is a singular figure, you know, singing about his or her own sorrow, but singing about it for everybody. That’s what I like. The intimacy draws me in—which is something I feel in lyrical poetry too, one consciousness speaking to another about what is true for them.

JEFF COREY

When did the blues begin to insert itself into your poetry?

ADDONIZIO

As I was learning to play harmonica, ten or fifteen years ago, I started doing it right away, even though I wasn’t sure how, exactly. I would just get up and torture audiences with my bad blues harmonica. I had to make myself play in front of them because I was terrified. But I made myself step up and do it. Luckily, I got a little better at the music. I began to figure out how to make it work—the harmonica is in your mouth so it’s a little hard to speak a poem while you are playing. One of the first things I did was learn a simple harmonica song and tag that on to the end of my reading.

Then I started to write songs in those blues forms, in the basic AAA—that call and response and a turn that takes it someplace else. I think “Blues for Robert Johnson” was the first one I did where I figured out how I could say the poem between playing licks on the harmonica.

AILEEN KEOWN VAUX

As a writer and a musician, how are your experiences similar and different as a performer?

ADDONIZIO

When I first started reading my poems I was terrified. It took a while to get comfortable in front of an audience. That doesn’t mean I never get nervous now, but I am a lot more comfortable getting up in front of people and reading. With the harmonica, I played with a blues band for a year and that helped me enormously, because we just got up and put out our equipment and did it. Ultimately, it’s about practice, about rehearsal. If I’m doing a solo piece or if I’m doing a reading where I know there is going to be music, I will really practice those pieces. I’ll have my set figured out between the words and the music and which harmonica I’m going to play.

KEOWN VAUX

How do you begin to explore a new art form, as you did with the harmonica, and incorporate it into your life as a new practice of art?

ADDONIZIO

You can study this throughout your whole life. And I hope to. I don’t listen to a whole lot else. I like a lot of different kinds of music, but I find myself listening to more blues, because I’m also trying to learn the music, so if I have any free time, I’m sort of making use of it in that way. If I’m making pancakes, I’m listening to the blues. If I’m making dinner, I’m listening to the blues. I’m driving, which is when I practice my harmonica, I’m listening to the blues.

I’d probably get good really fast if I were playing six hours a day. I mean, that’s what professionals do—the guys who really play, and I’m not one of them. They practice six to eight hours a day. I don’t have that kind of time. I feel lucky I’ve gotten someplace with it that I can be okay. I don’t think I’m going to get to the point of mastery, because I’m too focused on writing. I’m just glad I’ve gotten to the point where I can enhance what I do as a writer with music.

KEOWN VAUX

How does your writing practice differ from your musical practice?

ADDONIZIO

Right now, I have a regular writing practice, usually nine to noon, five days a week. That has been my time. Morning is good for me—wake up, have some coffee. I have this time that feels completely free and mine. I don’t have to get dressed. I’ll close the curtains, shut out the world. And then sometimes, that will fuck me up, because I’ll get into that interior space and not be able to get out of it. So I won’t go out that day, because I’m too into it. It strips away the outer layer, and I feel so vulnerable sometimes that I can’t deal with the outside world. Sometimes it’s hard for me to stop it. But that’s the time I try to carve out.

COREY

Ralph Ellison says that the blues is an autobiographical chronicle of the personal catastrophe, expressed lyrically. In your book Ordinary Genius, you say, “When you explore your own life in poetry, it’s good to remember that no one cares.”

ADDONIZIO

You know, I had to sugarcoat that a little bit.

COREY

These two sentiments ring true, but they also contradict one another. What do you think about these two ideas in relation to one another in the context of writing the blues into your poetry?

ADDONIZIO

I think it’s about how you make an audience or reader care. How do you make an audience care about your personal troubles, your personal sorrow? That’s where the craft comes in. You’ve got to make it interesting. Nobody’s going to listen to you singing off key. You have to find a way to get the notes right. In poetry or any kind of writing, it’s about getting the words right. It has to beguile someone. It has to attract. It has to entertain or offend them. Wake them up or knock them down. Writing works in so many different ways. There is writing that hits us with its raw power. Then there are quiet things that put us into a hypnotic space and take us into other realms. But you can’t assume that your life is going to be important to anyone. It’s never going to be what it is to you, because you are the hero of your life.

COREY

What themes do you find emerging in your work when you write about the blues?

ADDONIZIO

Love is one of my preoccupations, as I’m sure it is with a lot of people. I think about Joni Mitchell in relation to this, actually, and how when I was a teenager, her album Blue was an important soundtrack for my life. All my poems are about my search for love, which doesn’t seem to cease—so many of her songs are about that struggle with finding love or negotiating love. I’m sure that was an influence.

Another of my preoccupations is human suffering, trying to comprehend it. Every writer has those obsessions that become their territory. Kafka said his whole writing territory was about going back to the two or three images that first gained access to his heart. I think all of that starts to become the focus of your writing, what you circle around, whether you’re writing about yourself or you’re writing persona poems.

I just wrote a piece for New Ohio Review called “Pants on Fire” they wanted essays on the subject of lying and truth in poetry. My essay mentions several of my poems and how I lied in them and what’s not true. I think those states of feeling are true, even if I might borrow something to make it a little more interesting or troubling or dramatic.

KEOWN VAUX

You talk about the “truth of the idea” in Ordinary Genius, and it struck me that—well, the details matter, but whether or not they actually happened shouldn’t be the primary concern.

ADDONIZIO

Right, and that’s where it goes back, for me, to song. Because the blues singers, you know, they’re singing, “My baby done left me.” Well, probably, sometime during their life, somebody did leave them, but they’re writing it like it happened yesterday, because it’s more powerful if it happened like, “Woke up this morning and my baby was gone.”

COREY

You said the blues struck you like lightning. And then it gradually evolved to this active impulse to play and a routine of practice. Did something similar happen to you when you started writing poetry?

ADDONIZIO

When I was struck by poetry, I had been playing the flute. I took it up in my twenties, and played it seriously for about seven years, seven days a week, playing, living with a composer. Then, when I got struck by poetry, I realized immediately it was an art form, that just as I’d had to practice three hours a day on my flute to get anywhere, to get better, I would have to practice poetry. I understood that, which a lot of people don’t when they start writing. They just think, I’m going to write. But I understood right away that this is a discipline, I had to start applying myself, and that’s when I went to graduate school, at San Francisco State. My writing time was haphazard because I had a baby and I was a part-time single mother. I had to work and go to graduate school part-time for four years. It was like, write when you get on the streetcar and write on the way to school.

GOTCH

I was reading a piece Robert Palmer did on Led Zeppelin, in which he discusses how the blues became an important lesson for Robert Plant. He quotes Plant as saying, “With the blues, you could actually express yourself rather than just copy, you could get your piece in there… I could use several blues lines, well-known blues lines, but they were all related to me that day. And that’s because the blues is more elastic.” What makes this genre such an effective outlet for self-expression and collaboration?

ADDONIZIO

I’m doing that not only with the blues but with literary traditions as well. I’ve found myself writing more allusive poems and bringing in lines, whether straightforward or torqued from other poems. It’s the same as jazz. A musician will steal a lick from somebody or play a lick in homage to someone else. A horn player will drop in a Charlie Parker lick, and everybody will recognize it. I think I’ve just been doing that more as a practice in my writing in general. It’s a way to interact with the tradition, with those songs, with poems. As Janis Joplin said in “Ball and Chain,” “It’s the same fuckin’ day, man,” and I think that’s true—it’s all just the same fuckin’ song, man.

It’s call and response. Which is part of what the blues is about. You know, poets and writers don’t use melodies, but we’re still singers. And I think allusion is a way to blend, connect, be a part of the same song. Whitman was talking to us when he was writing. He didn’t know us, we weren’t alive yet, but he was talking to us. And we can talk to him.

KEOWN VAUX

The idea of collaboration seems like an important facet in your work—from My Black Angel to the craft book with Dorianne Laux. How has collaboration affected your work?

ADDONIZIO

It’s broadened it, and I hope to collaborate more, especially with musicians. My Black Angel is going to have a CD with it. We’re going to Houston to record, and I have no idea what that’s going to be like. But I’m really excited, because we’re going into a studio with professional musicians and some of the poems to figure out what the CD is going to be. It’s a cool direction.

I don’t have enough music people around me to do it a lot, so when I come to Port Townsend, I can do it here at Centrum, because I have collaborators that I know I can work with. In general, in my life, in Oakland or New York, I don’t really have those people. One reason I’ve tried to do some stuff on my own is that I can still pull in another art form I think audiences like. I feel like I’m an—I don’t want to say ambassador, but I want to bring this music, this African American music, to audiences. Because of where I am as a poet in my career, I have that audience. I want to bring the blues in front of them, say look at this tradition, look at this part of our history.

I’m performing at a blues and word festival in Florida. After I visited the first time, they decided they wanted to have me back and to have a blues band this time, so I’m going to collaborate with musicians, where the students are going to write blues poems and have a competition to read their work on stage with musicians. It’s nice that these interests I’ve had have come together in a way that I’m lucky enough to perform with some people and to make something happen.

COREY

In that sense, do you think of your full body of work as collaborative?

ADDONIZIO

Yes. It’s ultimately all part of the conversation. It’s one little part. It’s one voice.

COREY

Outside of the blues, another subject throughout your work is drugs, alcohol, addiction—do you see the relationship your characters have to their addictions as romantic?

ADDONIZIO

I have romanticized it, like a lot of people have. And that’s probably not a good thing to do.

COREY

You’ve said you write from emotion rather than autobiography. Do drugs and alcohol serve as a kind of tool to access that emotional truth in your work?

ADDONIZIO

The first rule of fiction is that only trouble is interesting, so you go where the trouble is. I think that’s part of it. Any kind of bad behavior is interesting and compelling, in the way that the ordinary and routine of life aren’t. So I think that’s definitely a big piece of my process—looking for trouble. And I spent a lot of my twenties doing drugs and drinking heavily, so that comes into it.

COREY

The way you maintained the narrative throughout Jimmy & Rita made me reevaluate what a short story collection or a book of poems is.

ADDONIZIO

I wrote one poem about those two people, and I decided that for some reason, I wanted to figure out their story and write a book about them. So from one poem, I had the idea of writing a novel in verse about them. That’s when I had to figure out who they were and write the book.

COREY

And then another book—

ADDONIZIO

I wrote a novel, continuing their story. I had to do it as a novel at that point.

COREY

What is it about these two characters that led to so much creation?

ADDONIZIO

They came to me and wouldn’t leave me alone. I was involved with them for a number of years. I think the narrative impulse has always been there for me; I was a narrative poet. Now I think that narrative impulse has gone into stories. I created characters and felt that they were very much alive. I thought I was done with them with the book of poems, but then I wanted to get them to a better place. I wanted to know what happened after the ending of Jimmy & Rita, when Rita is in a homeless shelter and Jimmy is God knows where. So I started the novel where Rita returns to the shelter one night, and she’s looking for Jimmy in San Francisco.

COREY

Are there any current projects where you’re like, I just need to blow this up into something bigger or into a different genre?

ADDONIZIO

No, there isn’t. I don’t know what’s going to be next. I have a play I wrote a draft of that’s not working at all, that I’m afraid to go back to because I don’t know if I can fix it or make it work. Other than that, I sort of have nothing, which for me is a scary place to be. I like it when I can say, Okay, I’m building toward a project. And then, when the project is done, my immediate feeling is, Where’s my next project? Help, I need a project! I have to find something to focus on.

COREY

Jimmy & Rita: The Musical?

ADDONIZIO

It would have been a great play.

KEOWN VAUX

Stuart Dybek has said that when he sits down to write he doesn’t really know what direction he is going in. He might write a story for a little while and then stop when he realizes, Aha! That should have been a poem, revising the piece in that direction. You write in so many genres. Do you prepare and plan for your work by genre? Or do you wait for the piece to show its true colors?

ADDONIZIO

I usually do have a genre in mind. Like one day, I might say, I want to kick back and write poems, so I’ll start reading through books of poems. Or I’ll decide I want to finish a story collection, like The Palace of Illusions, the collection that’s coming out. Once I decided I was going to work on some earlier stories, I was inspired to write new ones. I was supposed to be writing poetry at the time—I was on a poetry fellowship—but I was reading fiction and getting inspired to write it, so I ended up doing that.

Recently, I’ve been working on a book of essays, so it’s either essays or poetry right now. Poetry is sort of my fuck-off time, because writing poems feels the best to me. Like I’m just going to do what I want and write poems. Whereas everything else kind of feels more like work—even though nothing comes super easily. I actually have notes from my agent about this book of essays I’m working on that I haven’t looked at yet. Because I didn’t want to have to think about what I needed to do to work on those essays while I’m here. I just thought, I’m going to wait until I get back, pick a day where I go, Today is essay day, then sit down and read my agent’s comments and start to work again on those essays. But really when I go back, I’ll probably go, Fuck it, I just want to write a poem today.

I have to read in the genre I’m writing in—I have to be really careful not to read out of the genre. Because if I started to read stories, I’d probably start working to write one. And I don’t want to do that now. I’m done, right now, with the stories. Right now, I don’t know if I’ll ever write another short story or start another novel. I don’t ever want to write another novel, if I can help it. They’re so fucking hard. It just so long and, God, you never know where you are. If you go down the wrong road, you have to throw away a bunch of pages. It makes me crazy. I guess I did it to see if I could, because I like to challenge myself, but at this point, I don’t really want to do that again. Right now, I’m reading essays, and I don’t want to read anything else. Except poems. If it’s a poem day, I’ll read poems.

KEOWN VAUX

You mentioned a new collection of essays—do you have a shape or theme for this new project?

ADDONIZIO

It’s called Bukowski in a Sundress. That might give you some idea. And the subtitle, right now, is Confessions from a Writing Life. It’s personal essays about sex and writing. Everything is from the lens of being a writer, but it’s also certain experiences from my life. It’s more memoir, in that it’s supposed to be entertaining essays about being a writer and situations I’ve found myself in.

COREY

Speaking of sex, what is the relationship between loneliness and sexual desire in your work? I’m thinking specifically about “Summer in the City.” [hands her the poem]

ADDONIZIO

I have not looked at this poem in a long time. It’s like somebody else wrote it. I remember at the time that I was taken by Hopper’s images that seem so isolated, so full of ennui, and I guess I was drawn to those and wanted to recreate that effect in a poem. I wanted to do a series on Hopper. It didn’t pan out. There is only “Summer in the City.” His images make you want to know what the story is. The poem was triggered by the image itself and trying to recreate that in language, whereas other poems may come from my own loneliness and trying to express that state.

KEOWN VAUX

I notice that across all the genres you write in—the way you express this state of longing, specifically centered around how women look at men. Do you think you’re creating something akin to the “female gaze?”

ADDONIZIO

I don’t think I tried in any way to do that. Whatever came out came from my perception, but there wasn’t an attempt to turn around the male gaze, or do anything like that. It was more about trying to write something, to be honest about a certain perspective. I don’t tend to think in abstractions, it’s more what the moment brings out and then stepping back to take a look.

KEOWN VAUX

In A Box Called Pleasure, characters talk about performing for one another, then they say to the reader, “We are performing for you.” Performance and pornography are inextricably linked. Would you talk about the intersection you see between explicit writing and writing in the pornographic mode? Have you, or others, ever categorized your work as pornographic?

ADDONIZIO

In that book, for a number of pieces, I was figuring out different ways to write stories. I was reading people like Kathy Acker and George Beattie. I was reading Marquis de Sade. I was reading literary, pornographic texts in addition to Sontag’s essay on the pornographic imagination, in which she addresses using pornography as a literary mode. I was interested in these writers who were pushing boundaries. I could go out in this book and not have any limits on what I was writing. I could say the most outrageous things. I think that’s what Kathy Acker taught me. I feel the same way in poetry when I read Sharon Olds. You know that feeling of—What? What is she saying in a poem? I had no idea you could say things like that. I decided imagination is free and I can make it go anywhere I want.

GOTCH

During her reading last night, Erin Belieu talked about some poems being uncomfortable for her to read in public—but she read them, and I think she even said a few times, you know, “I’m never reading that one again.” Have you had a similar experience?

ADDONIZIO

It depends on the poem, it depends on the audience. I keep saying poem, but I have to remember I’m a fiction writer as well. I remember reading from Jimmy & Rita at a community college and feeling like, This is a big mistake. And at the end of it, sure enough, one of the students raised her hand and said, “Why does your work have to be so nasty?” I said, “Well, what do you mean?” And she said, “It has a lot of curse words in it and these bad things happen and I don’t understand the people.” I said, “Life is like that sometimes. And maybe it’s not for you right now, but this is what some people’s lives are like.” I’m trying to present that because I think all aspects of life should be presented. There shouldn’t be anything we’re not writing about or thinking about, in terms of human experience.

KEOWN VAUX

I’m curious about how you address what it is like for a woman to walk around in this world, specifically, with respect to two of your poems. If you put “Dead Girls” and “Augury” in conversation with one another, what would they talk about?

ADDONIZIO

I think they’re both about being a girl in the world, a woman in the world, you know, because we’re powerful, but we’re vulnerable, too. I think that’s what it is—both aspects. Boys and children are vulnerable in that way too. Also, the predatory aspect of sexuality is so powerful. I have a daughter. At the time I wrote “Dead Girls,” Polly Klaas had been taken from her home in Petaluma and raped and murdered. My daughter was the same age at the time, so I think there are three poems in that book about children who are abducted. It was very much on my mind, being the mother of a girl child, and thinking about how vulnerable she was in the world. And ”Augury” is the other side of the coin, a women’s beauty and power, girls coming into the awareness of their power, a girl on the verge of beginning to recognize her sense of herself. I know it happens for boys in a different way. But I don’t know that—because if I would have had a boy, I would have been writing different poems. I had a girl, so I didn’t get to see that side of it.

COREY

Because augury means how things will happen in the future, do you see this more as inevitability or an idealization of things to come?

ADDONIZIO

You mean making my daughter Helen of Troy? I think parents do feel that way about their children. We admire the hell out of them.

We love them so much. And when you see your child so uncertain about herself, and getting dressed up for the prom and getting ready and checking herself out—Do I look okay?—and you’re looking at her, just stunned by her beauty. It’s interesting, not seeing your own beauty, which you know, we all struggle with.

COREY

You’re someone who has built a career as a writer without being affiliated with any particular institution or university.

ADDONIZIO

I basically chose to be an entrepreneur, to be in business for myself I didn’t like working for people much. Over the years, I’ve worked as a waitress, at an auto parts store, for a car dealer and at a ball bearings manufacturer—a lot of auto-related jobs. I didn’t like having to go to a job every day. So teaching would seem the ideal thing, because you have a lot more freedom when you’re teaching, but then when I got into academia, I felt stifled by it. I loved going to graduate school, I had a great experience at San Francisco State—I learned a lot and had some good teachers and met fellow writers. But I was teaching composition, and I didn’t like that much. So I thought, I’ll teach creative writing, teach to people who want to hear what I have to say and not the comp students who don’t care and aren’t interested in creative writing. But I didn’t have the credentials to teach creative writing full time—I don’t think I had a book out or anything—so I started trying to do it on my own. I tried to become a bartender, and then right when I was about to take a bartending job, I thought, Well, maybe I could start a writing class, and if I can, maybe I won’t have to take the bartending job. I got enough students after my third attempt for a private class. It’s about temperament. I couldn’t handle academia. I wanted to be an artist first, which meant I had to figure out my own shit. On the other hand, without the university, I don’t think I could have survived. The readings I give around the country at different universities are significant pieces of my income.

COREY

When you talk about being an artist first, does that influence how you allocate your time?

ADDONIZIO

I have made art the priority, and that’s not to say anything about people who have university jobs. Everybody has to do something to survive. I’m at the point now where I wouldn’t want a full-time university job, but I’ll be a visiting writer in a heartbeat. I did that recently and loved it. It was fun to come back to a campus. Although I remember arriving at San Jose State and feeling a little freaked out, like, okay, there are grades, I have a little cubicle, I have these keys, I have an office, I have to have office hours. I was nervous my first day there, but then it was great—because I love teaching.

I pay my own health insurance, and have for most of my life. Right now, I’m on really cheap insurance in New York that doesn’t cover anything unless I get seriously ill and land in the hospital, in which case I’ll only be set back $10,000. Because that is my deductible. And it covers just about nothing. So this year, I’m just not getting sick. I’m not going to the doctor. I can’t afford the health insurance I had before. So I’m not sure what my next step is.

KEOWN VAUX

Move to Minnesota.

ADDONIZIO

Yeah, exactly. Because they have a really good arts council there and you can get big grants from them. Or Massachusetts, where health care is basically free. That’s another possibility. But those are the kind of things that are my considerations. Whereas, if I’d been teaching in a university for twenty years, I would have health insurance, I would have all kinds of benefits I don’t get as a freelancer. So it’s a little more uncertain, but I’ve gotten comfortable with that. I’ve gotten used to the ebb and flow. Ah, shit, I have a great life. Let’s face it. I mean, oh, God, the ebb and the flow and the uncertainly, the drama of it all? I fucking love my life. Because it’s all centered around doing what I love to do. I’m a writer. That’s my primary thing. And I get to do that, and make some kind of living at it. It’s amazing.