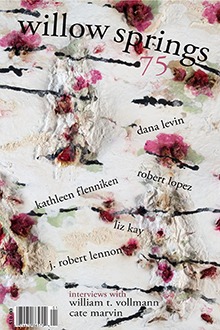

About Dana Levin

Dana Levin is the author of three books of poetry, most recently Sky Burial, which the New Yorker called “utterly her own and utterly riveting.” New poems and essays have appeared in he New York Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, Poets.org, Boston Review and Poetry. A grateful recipient of fellowships and awards from the Rona Jaffe, Whiting and Guggenheim Foundations, Levin teaches at Santa Fe University of Art and Design in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

A Profile of the Author

Notes on “Melancholia”

I’d been finishing a manuscript obsessed with End Times- which is to say, anxiety about the future: the one being built by the extreme polarities of our age, the one the global technocracy wanted to put in every hungry hand. Then, at Christmas 2013, a cousin killed herself. There’s a lot of bipolar disorder and clinical depression in my family; my cousin’s death- the third suicide in seven years amongst my cousins and siblings (two “accidental,” this one not)- threw me back into thoughts of my father, an untreated manic-depressive for most of his life. A rager, an eater: he was the Jupiterian god who ruled my house when I was young, a father I adored and feared. Even as a child, I sensed we shared an ambivalence about being alive, though mine I think was more situational than biochemical. It seems ironic, in retrospect, that that ambivalence found expression in excess: eating, buying, sucking the air out of a room. Not so ironic: hobbies of risk. The stories I always told about him- the one about the helmet and the crash, the one about the fight he picked on a stranger’s driveway, the car and the flood, the way he hoarded candy- surged for the first time to the page. I kept writing, even though the material seemed such a strange swerve out of my End Times orbit, but by later drafts I understood: no swerve at all, just a layer down, into one experience of the psychological underpinnings of civilization and its discontents, to use Freud’s by-now understated phrasing. Raging, eating, hoarding “candy”: what is this world suffering under but unfettered consumption and hobbies of risk? How else to understand what drives the choices we currently make and refuse to make where the earth, the collective, is concerned? From world leaders balking at eco-conservation to my father’s wrath at my mother’s attempts to limit butter- my own excesses with food and media- the drive of want, its daemon of lack and desire, is the same. And driving that: the mind straining against the bonds of the body. What then, future?

I wrote these father stories down in a conventional narrative mode and thought at first I might be at work on an essay. I could see the path to memoir unfurling, but something in me resisted. I wanted prose and I wanted a poem: the resulting form is the bargain struck. In terms of narrative and timeline, I felt an impulse to make the visible a little hard to see, to quote Wallace Stevens. Later, that felt psychologically accurate: we remember things in flashes, in memories and reflections out of temporal sync, blurs of dream and life. I threw my father’s heavy shade like a stone into a pond, watched associations ripple: movies, images, dreams. The world too seemed to be ruled by a bi-polar father-god, unconscious, suicidal; the way we were living under regimes of extremity, from weather to wealth. The poem built a thought-nest to brood an egg of knowing: why I am where we are.

Notes on Reading

I don’t think “Melancholia” would have found its final form without the influence of three books I read a couple of years before writing it:

Pam Houston’s Contents May Have Shifted, Craig Morgan Teicher’s Ambivalence and Other Conundrums, and, especially, Lucy Corin’s piece “A Hundred Apocalypses” in One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses (my kinda book). All three work in short prose flashes; all three work with an economy and compression we associate with poetry. Teicher’s book especially blurs the thrum-lines between poetry and creative nonfiction; Corin’s between fiction and poetry. Houston’s book has ‘refrain’ sections (various tales of hair-raising plane flights-, horrifying!) that give it a sense of rhythm and return we find in poetry. I really loved the experience of reading these books: swinging from room to room, as it were, in the house of the larger piece; a modular, rather than linear, approach. As writers, I think we read to learn, even if we think we’re reading out of obligation or for pleasure. We read to find, and, sometimes, offer each other paths and permission.