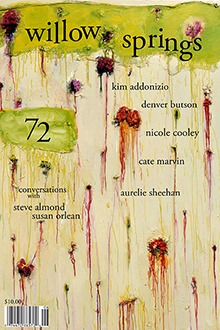

Found in Willow Springs 72

April 12, 2012

MICHAEL BELL, KATRINA STUBSON, ERICKA TAYLOR

A CONVERSATION WITH STEVE ALMOND

Photo Credit: Sharona Jacobs Photography

The voice in a Steve Almond story or essay or blog post is unmistakable, shaped by a tone typically anchored in dry wit, and a sharp, hungry intelligence that seems capable of taking us anywhere. The world, as Almond observes it, is at once hilarious and pathetic, sad and intensely beautiful. And it’s his willingness to engage the world that demands our attention. We follow him as he navigates his or his characters’ movement through anger and passion, sex and song, confusion and clarity and political rage, sometimes as a call to action or a commentary on our culture, sometimes as a portrait of the individual in crisis or struggling with the risks and dangers of being alive, and often from a depth of obsession—about music or politics or candy or sex or whatever else engages his curiosity.

“What people are really reading for is some quality of obsession,” Almond says. “They have this instinctual sense that the person who’s writing can’t stop talking about this, is super into it—scarily into it. Because everybody has what they’re obsessed with, but you’re sort of taught not to get into it because it seems crazy and makes you weird, and you should be able to get past that and stop collecting Cabbage Patch Kids or whatever your obsession is… But we are all, inside, obsessed.”

Steve Almond is the author of ten books of fiction and nonfiction, three of which he published himself. In 2004 his second book, Candyfreak, was a New York Times bestseller and won the American Library Association Alex Award. In 2005, it was named the Booksense Adult Nonfiction Book of The Year. His Story, “Donkey Greedy, Donkey Gets Punched” from his latest collection, God Bless America, was selected for Best American Short Stories 2010. He is a regular contributor to the New York Time’s Riff section and writes regularly for the literary website, The Rumpus. Two of his stories have been awarded the Pushcart Prize.

We met with Mr. Almond at the Brooklyn Deli in Spokane, where we discussed small publishers and big publishers, politics in fiction and nonfiction, obsession and more obsession, what makes a good editor, and how, “in the most emotional moments of a story, writers are trying to sing.”

KATRINA STUBSON

You’ve published books with different houses, and you’ve recently put out chapbooks yourself. What has your experience been like working with different publishers, large and small?

STEVE ALMOND

When you write something accomplished enough that somebody will buy it, that’s an important and amazing accomplishment. But in the euphoria of that—what I tended to overlook, anyway—is this unnatural arrangement, the artist in partnership with the corporation. It’s strange and unsettling for the weird, little freaky things that I have to say—whether in fiction or nonfiction or letters from people who hate me—to be turned into a commodity. What I want is just to reach people emotionally. I don’t want to feel that there’s a price tag on that, though I do charge for those DIY books I make, because they cost money to print and I’ve got a designer I want to pay and I also want to get a little bit for the energy and time I put into them.

I think it’s fair for artists to get paid. And I will say to people now—though I wouldn’t say it earlier in my career—I will not work for free. If you’re getting some money out of it, I’d like some money too. Doesn’t have to be a ton, but if you’re getting dough out of it—if it’s a nonprofit thing, a charity thing, okay. I’m thinking about this agent who sent me a note saying, “Would you be willing to contribute to this anthology?” And I was like, “Sure, just tell me who’s getting paid what and we can decide what seems fair for me.” And he just kept ducking the question. Turned out he was getting a fifty-thousand dollar advance. I was eventually like, “Yeah, I’m not cool with that. If you’re getting money, then all your contributors should be getting some money too.” I’m not naïve enough to be saying, “Oh, we’re just artists, everything should be free and open.” No. You work hard, you should get paid. We should have enough esteem for people who make art to acknowledge it’s worth paying for, worth supporting them in their endeavor. But working with a big company—I knew that they liked my art, but they were mainly trying to figure out a way to make money. They saw Candyfreak and thought, Oh, with our platform and marketing, maybe we can get this guy to write a bestseller. I understand that most editors are interested in good books. But most editors aren’t the ones who acquire books.

There’s a whole marketing team and committee and they have to decide if this thing’s going to make money or not. That’s a calculus that can start to infect your process if you think about it too much. You think, Well, maybe I should do this or that, and then you’re not really following your own preoccupations and obsessions. You’re worrying about what the market wants, what the marketing people want in a particular book.

In Candyfreak, the publisher begged me to take out a line at the beginning of the book that had the word “dick” in it: “You give a teenage boy a candy bar with a ruler on the back of it, he will measure his dick.” She was like, “Can’t we please take that out so we can broaden the audience of this book.” I understood what she was saying. That was a corporation speaking directly to the artist, saying that even though that’s the right word, and even though you want to write a book with a profane edge to it, we could really broaden our audience here. This could be a young adult book that could be marketed in a whole new way, be happily and safely given to kids, and so forth. I’m not blaming this woman for saying it—it’s just the voice of the corporation—but I had to say, “No. Sorry you’re pissed off at me.”

As far as those chapbooks go, I think if you’ve spent long enough making decisions at the keyboard, and if you feel like you have a book or books that you’re ready to move out into the world, books that don’t seem to need an editor—I mean, I had my friends edit those little books—then why not? The technology exists, the means of production for literary art has been democratized to the point that all of us can make a book tomorrow if we want to. Why bother to get a corporation involved when the project is a smaller, more idiosyncratic book? Why not put it out in a smaller, more organic, personal way? To the extent that your patience and talent allows, you can choose your publishing experience now.

I’m happy to have books published with big publishers. I’m happy to have anybody help me out with this stuff. I don’t like schlepping books around and having to do all that stuff. It’s sort of low-level humiliating and kind of a drag. I’d rather have somebody else do it all for me and I could just be the artist, with my little artist wings saying, Yes, I’ll sign your book. Now let me go off and write some more. But that’s not really how my career works. The culture doesn’t have that kind of passion for the work I do. But as long as the means of production exists and I have these little weird projects I want to do, why not try to do them in a way that feels more natural? It’s a smaller thing. I like the feeling of making a book with another artist, putting exactly what I want into it, sometimes in consultation with readers early in the process. There’s no marketing team, no publisher, no editor to mess with you about that—it’s liberating. And even though I charge money for the books, they feel more like an artifact that commemorates a particular night, a reading or some other interaction, rather than a commodity you could get anywhere, not that there’s anything wrong with buying books in stores. But I don’t think a lot of people walk into a bookstore and say, “What do you have by Steve Almond?” Nobody does. Or very few people. My mom does. I realized at a certain point that people find my stuff because I do a reading or give a class, and they think they might like more. You sort of have to recognize where you’re at, and for me, these DIY books make a lot of sense.

I’m delighted God Bless America came out with a small press. I’m glad I didn’t try to put that book out myself. It really only works economically when they’re little books. And Ben George at Lookout Books was a phenomenal editor, and helped make all the stories in God Bless America way better than they were before, even if they’d been published in the Pushcart or Best American. That’s the thing that matters—finding a great editor. Stephen Elliott says there’s no point in putting out twenty thousand copies of a mediocre book. You only have enough time in life to put out so many books, and you invest all this energy, so you’ve got to find the editor who’s going to help you make it the best book possible.

STUBSON

What makes a good editor?

ALMOND

A good editor pays attention. They get what you’re trying to do, they see the places where you’re falling short, and they can explain the problems in precise, concrete terms. Ben George would go through these stories and say, “You have this character shrugging here and I just don’t think it’s doing any work.” A good editor targets what’s inessential in your work, every moment you’ve raced through when you should have slowed down, every place where the narrative isn’t really grounded in the physical world and you’ve missed an opportunity. It’s a revelation to get that kind of editing, and it has everything to do with the quality of attention they’re paying to your work. It can be oppressive when it’s somebody like Ben, who’s so compulsive about it, though it’s also an incredible gift to have somebody who understands your intention so clearly that he can zero in on places where nobody else—great magazine editors, editors of anthologies—has said anything. He zips right in and says, “You don’t need this line. That word is a repetition. You need to show me the airport right now because I cannot see it.”

That hasn’t always happened for me. My editor at Algonquin was great, and my editors at Random House—I had two—did the best they could. But I think they were under certain constraints, and they weren’t line editors. They were essentially trying to figure out how to get a return for Random House on an investment they’d made. Their job wasn’t to make every essay shine and every line perfect and every word essential. I don’t think that makes them bad editors, in terms of how their jobs were defined, but it didn’t help me make the books better.

That’s not as true of Rock N Roll Will Save Your Life. My editor on that book was sharp about saying, “You cannot write ten thousand words about Ike Reilly. Nobody’s interested. You’re going to make the book worse and less accessible to the reader.” That’s a lot of what a good editor does—tells you when you might be confusing the reader, boring them, or writing in a way that isn’t compelling. Not because they want to sell tons of copies, but because they’re sensitive to the places where you haven’t made the arc matter enough to the reader.

ERICKA TAYLOR

How do you distinguish between being a political writer and a moral writer?

ALMOND

I do write about politics, and I get that people want to put whatever label on that, which is fine. I’m interested in cutting beneath the version of politics that’s happening on cable TV, though, and getting to the fact that it’s really all about policies and how people behave toward one another. In American politics, the big argument happening on cable has obscured the fact that we have elected representatives who decide how kind and compassionate and generous we’re going to be as a country or if it’s a moral duty for extraordinarily wealthy or even comfortable people to help out those who have less. There are moral implications to these decisions, and they’re almost entirely obscured in our political arena.

So when I’m writing political pieces, I’m trying to remind people that real moral decisions are being made about how your kids are going to be educated, or whether people in our culture are going to have the opportunity we say America offers. I want to remind people that we have great ideals in the abstract, but we almost never live up to them. America has the best ideals of any country on earth, and yet we’re the worst at living those values and enacting them. We’ve gotten completely distracted by this circus sideshow. But as I say that, I also recognize that I’m up on a soapbox, and that people don’t want to hear that. There are tons of people shouting from the soapbox, saying, “Here’s who you should be pissed off at, here’s what you should do.” You can become a kind of mirror version of what’s happening on talk radio. So I try to write in a way that forces people to realize that I’m talking about what it means to be a human rather than how they should behave morally. I don’t always succeed. I’m not sure my writing is always moral writing. Sometimes, when it’s not quite as good, it feels political and pedantic. I’m not sure that’s worthwhile.

MICHAEL BELL

How did you handle that in “How to Love a Republican” versus God Bless America?

ALMOND

“How to Love a Republican” started as a story based around the 2000 election and its aftermath. A liberal guy falls in love with a conservative. They’re both idealistic, political people working on campaigns, and when I originally wrote that story it was like 15,000 words, and 8,000 of them were me saying, “How can we have an election that’s so unfair?” and, “Dick Cheney’s such an asshole,” and, “The Supreme Court totally sold us out,” and blah blah blah. I had to look at those 15,000 words and see that they were a polemic, not a story. What’s more interesting is this human question: Can you love somebody when you don’t respect their basic sense of fairness and morality? How much do you have to agree with someone’s values in order to conduct an enduring romantic relationship? That’s the real question. And so the political polemical stuff got cut out of the story and what remained was this question of what you do when you love somebody and respect their ambition but run into this historical moment in which you can’t agree and you can’t let it go. Many relationships reach this point. It’s not necessarily about the 2000 election; it’s about some other thing—I cannot deal with the way you treat my family, or whatever it is. That to me is a much more universal idea to pursue.

The stories in God Bless America are reflective of the next ten years, the Bush years, and also since Obama’s been president. Our culture’s become meaner, more paranoid, angrier, more self-victimized. I think a lot of that comes out of how we processed 9/11. That was not a tragedy that caused us to do any reflecting. We just went into a crazy, bullying, narcissistic, jingoistic, proto-fascist psychosis. And of course 9/11 was a terrible thing. It’s not something I am going to try to appropriate—the grief of 9/11. That’s the crazy thing that happened on TV, because it’s a good story, and it became like every other story the media puts out: meant to press our buttons, not to really make us think about our duty as citizens or why we might have been attacked or what our empire’s up to. When I think about how we reacted to that, I feel like it’s cowboys and Indians. It’s this narrative of America as a heroic country that’s actually so empty inside that we have to regenerate ourselves through violence, make up a story about those nasty Indians attacking our forts we built on their land.

The stories in God Bless America are morally distressed stories, and they’re pretty depressing, and I feel bad about that because I like to write stories that have some humor— which is how I try to cut that moralizing I do. But that’s how I felt the last ten years. I walk around my house renting my garments and tearing my hair out, driving my wife crazy, saying, “What is this country doing? When are we going to grow up? It’s got to stop.” When I’m able to deal with that most effectively is when I’m able to imagine my way into a character contending with that world, a character who’s not me, who’s not an ideologue or a demagogue, but is just a person struggling with the first day back from war, having witnessed the kind of violence and chaos that young men are witness to in these wars, and coming back and somehow trying to deal with it. And he can’t. He’s broken and he’s going to take it out on someone.

The amount of that stuff going on—you don’t hear a lot about it. We’ve developed a narrative that the veterans are noble, wounded warriors. But when he comes back, we don’t listen to what he has to say. Maybe somebody’s paid to listen, but as a culture, we just clap in the air and say, “Thank you for your service,” and put a ribbon on our car and think we’re somehow dealing with somebody who got his legs blown off or had to kill someone or had his best friend killed or was shocked and freaked out by the kind of extreme violence he was exposed to. That strikes me as a fraudulent and immoral way to contend with that. So those stories with veterans in God Bless America are my effort to acknowledge that this is what happens. Like most people, I’m a civilian; I’m just trying to imagine my way into it. Maybe I’m doing a bad job, but I’m making an effort to ask what it would really be like to be nineteen or twenty and to be in that kind of moral chaos. To be in that violent chaos. What would it do to you? Who might it turn you into?

TAYLOR

We were talking earlier today about putting characters in danger. Since you were writing Candyfreak while you were depressed, were you conscious of the same M.O., and thinking, This book is manifesting me as a protagonist in danger?

ALMOND

It’s interesting that I was in the Idaho Candy Company factory and there’s Dave Wagers showing me around, and he’s such a nice guy, and I’m trying to distract myself. But then I have to go back to my hotel room and the reportage is over. If I were a journalist, I’d say, “The factory is so wonderful,” and it’s not really about me. It’s about how wonderful their chocolate pretzels are. And that’s fine for a piece of journalism. But with Candyfreak, part of my job was to turn the camera inward and be like, Also, I’m super depressed and fucked up, and that’s part of the story, too. It’s not the only part, but it’s a part. Maybe for some people it’s an indulgent or uninteresting part. But if I’m going to write about that experience, flying around to these places. I’m not going to ignore the fact that I was in a depression and doing everything I could to try to avoid it. To me, that’s what’s interesting.

And when I talk to the guy who makes Valomilks, of course I’m picking up on the fact that he’s this sort of desperate character who, on the one hand, has this story about how we’re bringing back old time candy and isn’t that awesome and wonderful? But it’s also a pitch he’s making, which he makes to all the journalists who talk to him. And that might be interesting as far as it goes, but it’s not literary. Literary is the sudden moment when a mirror is held up and somebody goes, “Oh, my god.” It’s the reason I left journalism, because the questions weren’t interesting. Who, what, where, when, why—not, Why did this guy fuck up his life? Why did this person have an affair? Why did this person make such bad decisions? What part of him got distorted into this particular evil? Those are the interesting questions, the literary questions.

With Candyfreak, my editor said to start right when we get to the factories. And she was pretty convincing and a good editor; she’s paying attention to the text. But I was like, I need people to know that I’m the person to write this book. And maybe what I was really saying was, “Maybe the book’s partly about me.” That sounded too indulgent to say directly, but I needed people to know that I have this especially pathological relationship to candy. And if they’re going to follow me on this, I want them to know they’re going to be following the craziest person about candy they’ve ever met. That happens to be the truth. I’m not some random reporter. With Candyfreak I wasn’t going to ignore the fact that it was me as a person who was obsessed with this one particular thing. The rock and roll book was the same way. I write out of my obsession. I think that’s the engine of literature. What people are really reading for is some quality of obsession. They have this instinctual sense that the person who’s writing can’t stop talking about this, is super into it—scarily into it. Because everybody has what they’re obsessed with, but you’re sort of taught not to get into it because it seems crazy and makes you weird, and you should be able to get past that and stop collecting Cabbage Patch Kids or whatever your obsession is. But kids are obsessive by nature, and they are the most voracious readers of all. They’ll read a book over and over again. They’re naturally obsessive, and we’re only trained out of it. But we are all, inside, obsessed. It’s just polite society that says, “Stop talking about that band so much. Stop talking about that TV show or website or painting or whatever it is.” I think most great books are obsessive either in their manner of composition or their plot, sometimes both.

STUBSON

We’re all obsessive by nature, but it’s okay because someone else is expressing it?

ALMOND

Right. People find stories or essays pleasing because they realize they’re not the only person who’s crazy, who’s that ruined or stuck in some way, or that joyful about something. I feel like everywhere outside of art, in the world of marketing and the day-to-day, nobody’s really telling the truth, nobody’s really going into any dark, deep, true shit. Everybody’s faking it. But a certain kind of person actually wants to get into that other stuff. It’s more painful to live with that kind of awareness, to be honest with yourself and other people, but I’d rather spend my time on earth that way, even though I’m now going to be poverty stricken and choked by doubt and all the rest of it. I think this is why so many people are getting MFAs and trying to do creative writing, or whatever art they’re trying to do. Because they’re deprived of the capacity to feel that deeply by the culture at large and, significantly, by their families of origin.

I grew up in a family where there was a lot of deep feeling and not much of it ever got expressed. It got expressed mostly through antagonism and neglect and a kind of avoidance of what was really happening. I think that stuff gets into the ground water of most writers. I write about it in This Won’t Take But A Minute, Honey. That’s where it comes from, that unrequited desire to say, “No, I’m gonna talk about this shit.” A lot of that is reaction to the fact that you come from a family where that stuff isn’t talked about. Your parents are like, “Are you depressed?” Their take is, Wow, it really would be easier and more efficient if you would just get a business card and a healthcare plan and have a more conventional lifestyle. I’m lucky that my folks are psychoanalysts, because they’re interested in the insides of people. But a lot of the people I encounter don’t have that advantage. And it’s not because their family is trying to silence them. Parents want their kids to have a happy life, and they see the life of an artist as an intense engagement with feelings—oftentimes painful feelings—and the struggle to make ends meet and to be heard in the world, and maybe a lot of disappointment along the way.

BELL

You talk about questions you’re interested in, for example the questions journalism asks as opposed to literary nonfiction. Are those nonfiction questions the same as the ones you approach in your stories, or are those central questions different?

ALMOND

Stories allow you to construct a world that’s completely aimed at exposing those questions. With nonfiction you have to choose your topic and root around through the past to find the moments that really mattered, and then you try to unpack them. But with fiction, my sense of plot is extraordinarily primitive: Find character. What is character afraid of? What does character want? Push character to scary cave or happy cave. When you know you have a character who’s a closet gambling addict and a shrink, then you know how the rest of the story has to go. Of course a famous gambler has to walk into his office, and of course they have to wind up across the poker table at the end of the story. As soon as you know what your character desires and fears, you have some sense of what you’re pushing your character toward—or I do. That’s my conception of plot.

With nonfiction, it’s much more a process of archeology and digging through and saying this moment is important, and so is this history. You can choose where to look around, but you can’t choose to make shit up like you can in a story. You’re engineering the world for maximum emotional impact in a short story. Whether you have the courage to do that or you get lost with all the possibilities is another question. When you have no constraints on reality, you can engineer any world you want, put your character in a room having sex with his secretary and in walks his wife, and boom—you just did it, it’s a dramatically dangerous situation. You can’t do that in nonfiction. You might write about your fantasies or wishes, but you have to write about stuff that actually happened and stuff that happens in your head. You can’t make stuff up to make it more dramatic. If you do, you have to call it what it is—fiction.

TAYLOR

Your flash fiction feels particularly lyrical. Do you approach very short work in a different way?

ALMOND

A lot of those started out as poems. But I realized they weren’t poems—they were little stories, little bursts of empathy. I read flash, and I always have a pleased feeling when a writer has somehow plugged into this exalted way of communicating. I feel like they’re singing to me. In those little stories, I’m just trying to capture moments where something devastating happens. I’m trying to capture five seconds in amber—like my great-aunt being walked across an icy street by this handsome young guy who calls back, “Can I have your number?” in front of his friends—a moment of gallantry and how beautiful that is. Nothing more than that. You don’t need to know her whole life. You don’t need to know where she grew up. This is the moment that matters. That’s what those flash pieces are about.

STUBSON

In Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life you write that songs taught you a lot about story.

Would you talk a bit about expression in song versus expression on the page?

ALMOND

Music allows you to reach feelings you can’t reach by other means. The best writing does that too, although it’s a lot more inconvenient because you have to sit there and pay attention, whereas if a great song comes on, boom, you’re in it. You have an immediate set of memories and associations and an emotional reaction. Reading is harder. In a certain way it’s more fulfilling, because with a piece of writing you have to do much more work than any other art form. You’re an active participant in the construction of these images and so forth. You’re making the movie in your head; I’m just giving you the perspective.

So that’s very exciting, but the reason I listen to a lot of music, and kind of always envied musicians, is that it just gets across much more quickly and intuitively through the primal and instinctual language of melody and rhythm. There’s no comparison. And you could ask almost any writer, at least any writer you’d want to spend time with, “Would you rather be a musician and go on tour and be able to do your crazy ecstatic thing of making music, or would you like to be a writer, sitting in your fucking garret going, Ughhh I hope, I hope, I hope?” That’s not to degrade writing. I think it’s great, I love it, blah, blah, blah. But the thing I learn from listening to songs and listening to albums—these guys want you to feel something and they’re not being coy about it. They’re not writing their little obedient, minimalist short story or earnest autobiographical essay. They’re singing; they’re trying to get across to you emotionally.

I think all young writers think, I have to be taken seriously; people have to know I’m a serious artist; let there be no confusion about that. And they’re more reluctant to get into the real reasons they’re working on a particular piece—to get their characters, whether it’s fiction or nonfiction, into that real emotional trouble we talked about. With a good song, you’re in emotional trouble right from the first chord. It’s an ecstatic, immediately emotional experience.

In my writing. I want to construct a ramp to these important emotional moments, slowly drawing the reader in. But I also think that in the most emotional moments of a story, writers are trying to sing. That’s what James Joyce is doing at the end of “The Dead.” That last paragraph is like a beautiful song. That’s what Homer is doing, that’s what Shakespeare is doing, that’s what all great writers are doing—Toni Morrison, Saul Bellow, Denis Johnson, whoever. They reach these ecstatic moments, and in order to describe the complex, contradictory feelings they’re experiencing, the language has to rise up and become more lyric and sensual and compressed in order to capture that kind of exalted moment, whether it’s grief or ecstasy or some complicated mix of emotions.

Listening to songs makes me wonder why I am not writing towards those moments where you just open your throat and sing. And if I’m not, then what am I doing? Of course, you can be sentimental and screw it up and I hate that kind of writing. It’s playing it safe. If the character isn’t at some point in real trouble, if the language doesn’t reach up into a sort of lyric register, what is the point? I’m not saying that’s how all writing should be, but that’s my feeling about it. If you’re not writing for those lyric moments, what are you writing for?

BELL

Are those germs for story? Do you know the moment, or do you start with the character and get there?

ALMOND

I usually start with characters and I have some sense of what they want or what they’re after, what they’re frightened of. And the rest of it, at least to the extent that you can, you’re trying to let your artistic unconscious steer. You might have broader sense of, Okay, Aus is a closet gambler and that’s got to be revealed somehow, and Sharp—I didn’t know who Sharp was—he walks in. I like that he’s got an attitude, I like that he’s sharp and jagged and well- defended, but I didn’t know he was going to start talking about his kid and reach this moment where his wife is on the brink of leaving. That’s just stuff—I don’t even know how to explain it. As you’re writing the character, suddenly that’s who he is, that’s what pops out. Undoubtedly it comes out of my own preoccupations and obsessions, but I’m not trying to figure that out as I’m writing. I’m just hoping my artistic unconscious is going to feed those moments where characters come apart against the truth of themselves.

You can engineer the plot to an extent, but the lines themselves and the journey that a particular character takes toward that moment should be a mystery to you. That’s the joy of writing fiction. There’s this mysterious thing that takes over. And to some extent, nonfiction as well. I didn’t know that Candyfreak would lead me in this, that, or the other direction. That’s part of the pleasure of writing. If you know it all already you start to feel self-conscious and predetermined. There should be lots of stuff you don’t know. That’s what allows you to surprise yourself and keep a preserved sense of mystery in your work. Your artistic unconscious has to deliver so much to you. It’s way more powerful than your conscious efforts to jury-rig things.

STUBSON

Can you consciously train your subconscious so that you can make those kinds of discoveries?

ALMOND

All you can do is be honest about the things that stick in your craw, without trying to psychoanalyze them or understand why. As a nonfiction writer, Susan Orlean becomes completely obsessed with orchids, and she just follows it. She doesn’t wonder, Why am I interested in this. What is it about? She just follows the trail. Can somebody teach you to be that way? No. You’ve got to find it within yourself. I tell my students to write about the stuff that matters the most deeply to them. In fiction, you don’t always know you’re doing that; you have to sneak up on it.

I wrote this story years ago called “Among the Ik.” It’s in My Life in Heavy Metal and it’s based on something that happened to me. I went to visit my friend Tom in Maine, whose mother had just died. Also, he’d just had his first child, a baby girl. I walked in the house and there was the baby and the baby’s mom and Tom’s brother-in-law and sister in front of the fire, and they were having tangerines. This beautiful tableau. But I walked into the kitchen first and there was Tom’s dad, and Tom introduced me to him, this grieving widower, and he’s nervous and for whatever reason, rather than allowing me to move into where the action is, where the new life is, he nervously cornered me and found out I was an adjunct. He was thinking, I guess, about when he was an adjunct, and he told me this story about having to identify the dead body of one of his students.

It was a weird story, but as a fiction writer you’re always on the lookout for that. It stuck in my craw. I don’t know why it did, it just did. I sensed that he was frightened to integrate with the rest of the family. So for whatever reason, this lonely guy telling me this story about a dead body gets in my craw and I start writing about it. I’m not investigating why. I just know it’s stuck in my craw and that usually is the signal to me that I need to write. So I write this story and I change a bunch of things—he’s a poet in real life, but I make him an anthropologist. My artistic unconscious feeds me this memory of when I was in second or third grade and we watched this film about a tribe somewhere called the Ik, and how the environment there is so unremittingly harsh that parents sometimes leave their children behind. It haunted me for years, rolling around my subconscious, and up it pops the moment I needed it in this story, when I’m writing about parents and kids and families and how they connect emotionally or are unable to connect emotionally.

I finish the story and when My Life in Heavy Metal comes out, my dad sends me a long note saying, “Oh, gee, Steve, your mother and I really like the stories; we’re very, very proud of you, and about that story ‘Among the Ik’—I just want to tell you that I never realized I was such a distant father.” And my immediate reaction was, What are you talking about, Dad? That story’s not…about…you. It’s about that episode that got stuck in my craw. When I wrote it, I didn’t sit at the keyboard and wonder why I’d been thinking about it so much. I just chased the story.

I don’t think you can train your mind. But you can spend time at the keyboard and you can try to be relaxed when you’re at the keyboard and write about the things that you’re preoccupied with and be as unselfconscious and as unremittingly honest as you can be. That’s about all you can do. I don’t know of any push-ups for your artistic unconscious. I just know that the best work I’m able to do is when I’m writing about stuff I’m obsessed with, especially with fiction, when I have no idea what I’m doing; my characters are acting on my behalf and my obsessions are disguised and I just sneak up on them.