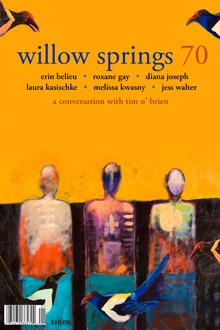

Found in Willow Springs 70

April 16, 2011

MICHAEL BELL, SAM EDMONDS, ERICKA TAYLOR, AND TANYA DEBUFF WALLETTE

A CONVERSATION WITH TIM O’BRIEN

Tim O’Brien’s characters occupy a world in which narrative has the power to consume, to unite, and to heal. Stories are repeated and memories revisited, until accuracy sometimes gives way to isolation, fear, and despair, until the only way forward is to keep telling them. “The best of these stories are memory as prophecy,” writes Richard Eder, in the Los Angeles Times. “They tell us not where we were, but where we are, and perhaps where we will be.”

Tim O’Brien was born and raised in small-town Minnesota. Upon graduating from Macalester College in St. Paul in 1968, he was drafted to fight in Vietnam, serving from 1969-70. When he returned, he became a graduate student at Harvard University, but dropped out to pursue an internship at the Washington Post, where he began work on his memoir, If I Die in a Combat Zone. Since then, he has written seven novels, including Going After Cacciato, which won the 1979 National Book Award, and his novel in stories, The Things They Carried, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and won the Chicago Tribune Heartland Prize and the Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger, a French literary prize for best foreign work of fiction. He has received literary achievement awards from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Guggenheim Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. He currently lives in central Texas and teaches at Texas State University-San Marcos.

We met with Mr. O’Brien at the Brooklyn Deli in Spokane, where we discussed absolutism and ambiguity, the slippery, evasive qualities of truth, crippling idealism, and how “we all do little tricks to try to erase our flaws, even from ourselves. We’ll fine tune, and we’ll try as much as we can to forget the bad things we’ve done and wish we hadn’t, and magnify those things we’re proud of. I think our country does it, too, and other countries as well where we erase what we did…. Nobody thinks about what their country did-how we once had slaves and once exterminated a whole race of people, the Indians. People don’t think about that stuff. It’s erased.”

SAM EDMONDS

You’ve said that one of your main themes is exploring the human heart under stress. In what ways has this theme changed from If I Die in a Combat Zone to July, July?

TIM O’BRIEN

Not at all. The stories change, but I’m always interested in exploring a set of circumstances or a character in trouble, how the trouble started and how it will be resolved, if at all. It’s like conversations you overhear on a train: some you’re interested in and want to explore, while others bore you. So nothing really has changed. I do think good writing is often about the human heart under stress. And I think bad writing has an agenda. It’s polemical oftentimes-makes a point, delivers a message, offers counsel or advice about something. For me, good writing is tentative. I don’t want to be an absolutist, but a good book is not one in which I detect an agenda, because art takes both sides of a thing; it doesn’t just present one point of view, it contains others-this character’s, that character’s. And even those points of view are often undermined or evolve throughout a book.

EDMONDS

In your interview with Big Think, you talk about news and news writing. Is that an example of what you consider bad writing?

O’BRIEN

There’s an absolutism to that kind of writing that has disturbed me since I was a little boy. I see ambiguity everywhere, including inside myself. It could be a serial killer we’re reading about, Ted Bundy or someone, and I’ll be interested not just in how evil he is and how he could have done what he did, but in his side of the story; what does he have to say about it?

I think that’s why I became a novelist. If I knew what I thought about everything, I’d write nonfiction: Here’s what I think. But I don’t know what I think about everything. On virtually any subject, I’m- I guess you could call it wishy-washy. That would be a pejorative way of saying it. Or you could say open-minded, but I don’t think of myself as that. I seek all sides of everything to a fault.

It explains a lot about why, in my books about Vietnam, I saw all sides in the war. I wanted to do what was right for myself and my country. I wanted to be faithful to my conscience, but I also loved my country and didn’t want to leave it. I felt paralyzed by these competing and ambiguous thoughts. And that’s true about love and fathers and mothers and everything in the world.

ERICKA TAYLOR

In Tomcat in Love and In the Lake of the Woods, your protagonists are aware of their desire to be loved. How does that need for love play out in your work?

O’BRIEN

Love separates us from dogs and mice-we know what love is. We crave it and want it, and sometimes it’s a really good, positive thing. But we can do evil things in the name of love too, like kill people. Like go to war: “I love my country, and I’m going to go kill people because I love it so much.” And that’s a macro, kind of gross example, but it’s true. “I love God,” and the Crusades come and you get millions of dead people. On a daily level, what we do for love-to get it and give it-includes tiny things: paying a check or smiling at somebody in an elevator so they’ll like us. You know, holding a door for a person. I want people to like me, and I think we all do, in small petty ways and in big political ways. More than we realize, our behaviors come out of a desire to be loved. To go into a war is a pretty good example of wanting my country to love me, as well as my mom and dad and hometown, even though I thought it was a bad thing to do. I wanted that love more than I wanted to love myself in doing the right thing.

MICHAEL BELL

You’ve written about going to war for that love, or going to Canada-

O’BRIEN

That’s an example of seeing both sides. Part of me is the person who went to Canada, who did the courageous and difficult thing of saying, “No,” which was, for me, really hard for the reason I just mentioned. I wanted to be loved. So, I didn’t say, “No.” I said, “Okay.” I like to write about characters who did have the courage to say, “No,” and who live with the consequences of it.

EDMONDS

You often use repetition in your work, for example, in Northern Lights, when Grace is calling Perry “Poor Boy,” telling him to “Lie down, lie down there. It feels better.” How important is repetition to your prose?

O’BRIEN

There are times when repetition has the effect of a song. If the chorus weren’t there, it wouldn’t really be a song, because it wouldn’t be unified. Repetition has that unifying function. It also functions to remind the reader of the “aboutness” of what they’re reading. It brings you back to a kind of center.

The tough thing as a writer is to know when repetition’s called for and when it’s going to get in the way. There are times when I’ll say, “I shouldn’t be doing it now,” and other times I feel like I have to. I have no formula or recipe for it; there’s a feel in phrasing each repetition, or there’s not. But I do think, in beautiful writing, there’s some kind of repetition that saves it from the prosaic or dull or monotonous-even if it’s just a phrase or a few syllables. It makes a work feel whole and unified, and without it, the work might feel kind of meandering.

BELL

Certain stories are repeated in your work, as well.

O’BRIEN

You’re right. The killing of the baby buffalo, for example, has appeared in three of my books. What I see in writing is what I see in life-recurrence. Life is full of repetition, and throughout my life, the killing of that baby buffalo has recurred-not in actuality-but in my dreams or when I’m sitting alone thinking about the war. I’ll see that animal and I’ll see it again thirty years later or ten minutes later. But I’ll always see it through slightly different perspectives. Sometimes it’ll be the perspective of anger-I felt angry the day it happened-and anger will bring it out of me. Other times it’s a sense of guilt-why should that poor animal have suffered for something it didn’t do? So the repetition is not always exact. That’s how memories keep coming back-the same way as with any writer: Faulkner, Hemingway, Fitzgerald. All drew repetitively on things they had written about before, but through different angles of vision.

TANYA DEBUFF WALLETTE

You’ve said that truth is a function of statements we make about the world. Can you talk more about that?

O’BRIEN

How can there be truth without declarations of truth? It’s a construct of language; the very word “true” is a word. T-R-U-E. And can there be T-R-U-E without the word? Little bits of truth go by, so there goes a hunk, and there goes another chunk, and there goes a piece. The declarations we make about the world are what we mean about things being true or not. So I say that this table is made of wood, and that’s a declaration. Ericka might look under it and see a piece of plastic attached to it. So it’s made partly of wood, but there’s plastic under it, so it’s not made of wood. The truth has been amended.

You could say it’s true when you say, “I love you.” It’s a declaration and it comes out of your mouth. When we say “true,” I guess it has to do with intent-does it feel real to the speaker? But two weeks later, the person says, “I love you,” and it may not be true, because time has passed and feelings change, people change. So the same declaration- exactly the same words-a month later, ten years later, may not be true anymore, even though they’re the same words.

I think language is what we’re looking at when we’re deciding whether something is true or not. There are more complicated examples, such as my Methodist minister back in Worthington saying to me, “Thou shalt not kill,” and developing a whole sermon on it. Two months later, I get to Vietnam and there’s this guy saying, “You better kill or we’ll court-martial your ass.” Can they both be true? Does it depend on the speaker if a thing is true or not? Who uttered it? There were certainly no qualifications made by that minister. He didn’t say, “Thou shalt not kill, unless your country tells you to, or unless it’s a Vietcong soldier.”

And so-when you’re a twenty-one-year-old kid, sent from that church to that war, and you’re told to kill people for causes you don’t believe in, that you think are plainly stupid and ridiculous-where’s truth? And what’s true about yourself? Am I the nice guy I thought I was? You wonder where truth resides, even within yourself. Then you come home and spend the next four decades looking back on it, angry at yourself and feeling guilty. Truth is just really difficult and evasive and fluid.

It reminds me of what we were talking about earlier, concerning absolutism. There’s a current in the world nowadays-it’s always been there, but now it seems more pronounced-a kind of absolute I’m- right-you’re-wrong. Turn on CNN and Fox. It’s right in front of you: “I’m right, you’re wrong. Here’s the truth of things.” There’s no humility. There’s no “Maybe.” There’s no “I think.” It’s just, “Here’s the truth.”

And that kills people: Stop the communists, those people are trying to invade South Vietnam. There’s no room for debate or to look at history-it’s just, “That’s the truth,” a simple-minded, zealous, fanatical, complacent, pious, self-righteousness that eats at somebody who’s been in war and watched people die as a result.

BELL

You said in a recent interview that art is cutting through rhetoric and convention to open a trapdoor in your soul. What art has done that for you?

O’BRIEN

There are so many beautiful stories that have done it for me. It’s a feeling of moving away from obligation as I turn the pages. Here’s a classic, and I’m going to find out why, I think with a little skepticism. And then I begin turning pages and this trapdoor feeling comes and I tumble through it, entranced. To name the books or the stories, you’d have to do an encyclopedia of great writing, because the trapdoors are all different and the fall is further and different in its feeling-a fall of sadness or lightness or happiness, of the miraculous-all kinds of different ways of falling.

TAYLOR

When you talk about falling through the trapdoor, do you have that sense of not wanting to leave?

O’BRIEN

Very much so. You can see the pages dwindling and you know the dream is going to end. When you’re actually dreaming, you don’t have that feeling; you don’t count the pages in your dream, so it feels as if it could go on to eternity. But with a book, when you’re lying in bed and you see the dwindling pages, there’s a sense of growing sadness-much like getting old. You can feel the end approaching. It carries a sense of sadness with it. But it carries a sense of resolution too, so it’s okay.

BELL

Is that something you’re conscious of when you’re writing the fictional dream?

O’BRIEN

I’m conscious of the story coming to a conclusion and that the characters are going to join not just other characters of mine and those I’ve read, but the literal dead and Shakespeare and my dad. There’s a sadness to that, that makes us human. I think it’s probably a sign of dominance, that we’re aware of our mortality. And I feel it in the writing even of short stories, that this is coming to a sad end, even if it’s a cheerful or joyful end.

EDMONDS

In the final footnote at the end of each “Evidence” chapter of In the Lake of the Woods, we hear what sounds like an essayist’s voice. Can you discuss those footnotes?

O’BRIEN

It’s an organizing device, for one thing, where the story of John Wade is being told by someone trying to discover what happened to him and whether he did it or not. This narrator, as the story goes on, is frustrated the way most readers are, and not getting very far, not getting much closer to what really happened.

I wanted his sense of frustration to mirror the reader’s; it was a way of diffusing pure frustration-to say that not just the reader is frustrated by not getting an answer to the mystery, but take it beyond that, to a narrator saying, “Well, at least I can accommodate not knowing by realizing that that’s life for you. We don’t know where we go when we die, and that’s life. Do we go to heaven with halos and harps? We don’t know.” People pretend they know, and this narrator says that religions are constructed to make up answers for what we really don’t know. We’re fooling ourselves, the way John Wade fools himself by building artificial constructs of what we call faith. But, you know, a non-believer is going to say, “I have faith that the table’s going to rise in three seconds, watch.” It may not rise, but for a true believer, that’s not going to do anything to their faith. You can’t debate with faith.

So the device is meant to organize this frustration about not knowing, but also to raise it to a level beyond the story, to the level of the world we live in. The most important things for most of us are unknowable. Did that person love me? You can’t know for a fact; you can’t get into somebody’s head and read their thoughts. All you can go on is evidence, how the person talked and behaved, and even then we’re fooled a lot. Even things about ourselves are unknowable. I wanted the book to go beyond the surface mystery of a woman vanishing and then a husband vanishing, and to reduce the gap of inevitable frustration. That’s part of being alive, and we’re all going to end up where John and Kathy Wade are. We’re all going to vanish from our lives. And where we’re going, we don’t know. It may be a good place, a bad place, or maybe back to nothingness. We don’t know.

TAYLOR

How did the three part structure of The Nuclear Age-Fission, Fusion, and Critical Mass-come about?

O’BRIEN

With that book, I was into actually counting lines and doing a kind of mathematical structure. I wanted almost what you do with poetry-and that was an error on my part. Not that the idea was bad, but it forced me to play a game I didn’t want to play. The aliveness of the novel is killed in part by the too-severe rules I put on myself.

It would have been a better book had I limited the story to the wife, the daughter, and the obsessed guy in his backyard digging a hole. I was too ambitious in my architecture, and the book suffered. It came out of a desire to make rules for myself and be faithful to them. Sometimes that works. I did the same thing with The Things They Carried, where I set up rules: I’m going to write a novel that reads like a memoir, and I’m going to obey all the conventions of memoir. You know, my own name, and dedicating the book to the characters in the book. I wanted to make it feel like you’re reading something that really happened, but then periodically say, “This is a novel, a work of fiction.” Those rules worked. They opened things where the other rules closed things. You never know which way it’s going to go, until you’re ten years done with it and sort of feel the result.

I do like to experiment with setting parameters that will structure story. I’m going to try these parameters and make them new and all mine-as new as I can make them, and then try to be faithful to them. Really good things can come out of rigid parameters, not always failures.

EDMONDS

Twenty years passed between If I Die in a Combat Zone and The Things They Carried. How would you differentiate those two books in terms of structure and theme?

O’BRIEN

If I Die was written as a pretty straightforward war memoir, but not entirely straightforward. I scrambled chronologies. The book opens in the war and circles back to growing up and then goes forward. Most memoirs are written as a straightforward chronology, and I wasn’t interested in that. I didn’t think it would engage the reader. The book is about a character’s experiences in Vietnam, and to get there 150 pages into the book seems to me to kind of cheat. Right away I was moving slightly away from the conventions of memoir. Nonetheless, If I Die is a fairly accurate representation of what I went through in Vietnam; the events occurred more or less as they’re described.

But you can’t put everything in. Should this memory go in or that one? All memoirs go through this selecting, and in the end, memoir is not utterly and absolutely faithful to what occurred. Memory fails. You can remember the feel of a conversation: “Oh, I love you,” Jean said. “Oh, I love you too,” Jack said. You can remember the “love you” stuff, but your memory is going to fail at what was said next, or what was said first. How you got to “I love you” is erased from your memory.

In writing If I Die, I learned distrust of truth. Pick up a newspaper. You’re reading what you take as absolute truth: “Today Richard Nixon blah blah blah.” You read it, but what you’re forgetting is that the reporter had to throw away all these other truths. His editor tells him, “Put in these column inches.” Everything else is thrown away. You’re getting part of the truth, but is that the truth if you leave stuff out? Where I come from, that’s called a half-truth. And you compound that because of all kinds of other variables.

In a work of history about the Battle of Hastings, say-you know, a history book-you’re writing about the battle, but you can’t put in every thought of every soldier as the battle unfolds. You don’t know every thought of every soldier. So, when you call a thing “true,” how true is the truth? I mean, is part of the truth true? I’m not saying that historians or newspaper writers lie. What I’m saying is, to bill something as the truth is suspect, and I learned that in If I Die. I felt I was reasonably faithful to what had occurred, but I knew I hadn’t held a mirror up to what had actually happened.

It was liberating to think, Well, if you could do that in a memoir, why not write a work of fiction, in which, through fictional strategies, you don’t have to worry about being faithful to the truth? There are different kind of truths you’re after, a feel, an emotional truth, a spiritual and psychological truth not tethered to the world we live in. You can leave that behind and search for truths that remain true despite the real world. People do bad things for love, good things for it. That’s the kind of truth that’s untethered to the world. So, they’re different in that fundamental aspect, these two books.

BELL

Could you extend that comparison to Cacciato as well?

O’BRIEN

Cacciato was born out of a real thing, a desire to run from war. I wanted to get the fuck out, and I fantasized about it during AIT-at Fort Lewis, where Canada’s ninety miles away. I’d be walking around the fort doing all this preparation stuff-you know, target practice and all the crap we did-knowing I could be on a bus and in Canada maybe two hours later. I dreamt about it-I don’t mean during sleep, I mean as I’m doing this stuff. I’d hold it out as a thing: God, if this gets bad enough, I can do it. As I wrote about it in If I Die, I kind of half planned it, thinking, Maybe I’ll leave.

Cacciato was born out of something similar. All through Vietnam, you’re carrying a weapon and war’s all around you and people die and you’re getting wounded. There are these mountains, and what’s to stop you from just walking into them? There’s no authority or MPs in the bush. You’ve got this weapon, so you can get food if you need it by holding people up. What’s keeping you in the war has nothing to do with the stuff that did in the States: authority and borders. What’s keeping you is social pressure. I want my friends to love me. I don’t want to be seen as a deserter. It’s all interior stuff that’s keeping you in this horror, when every impulse is to get out.

I’m not the first person to have written about this. Hemingway wrote about it in A Farewell to Arms and Heller in Catch-22 and Homer in The Illiad. The desire to flee the murder and homicide and mayhem is fundamental. You’d have to be insane to not want to do that. So the story was born out of real stuff, but I wanted to write something that extended this daydream I’d had in AIT, through the story of Cacciato; the soldier has an extended daydream. What if we went after Cacciato, what would have happened next? Would we have made it to Paris? And what would have happened in Paris? Could I have lived with myself walking away from a war?

It was kind of a mirror to what I was thinking during those nightmarish days at Fort Lewis, when I couldn’t quite get myself to imagine crossing the border. I couldn’t quite get that far. But this character in the book, Paul Berlin, could see himself, or at least imagine himself, doing it. It’s a made-up story, but it’s born out of a real thing.

TAYLOR

Were you trying to play with truth in Tomcat in Love, with Chippering’s obsession with words and what they mean?

O’BRIEN

I wasn’t playing with truth exactly, but with the endless hairsplitting and self-justifications of our own bad behaviors. It was written during the Clinton era, so I was kind of modeling it on that Monica Lewinsky stuff, you know-“It wasn’t sex.” You draw these fine lines about whether blowjobs are sex or not and it’s just laughable. It was kind of the world around me, a guy who has no filter over what proper behavior is. It was written about the relentless remorselessness of his sexism. He just couldn’t and wouldn’t stop. He’d go through one demeaning, horrendous happenstance and march into the next one, the way, through history, we’ve all-mankind-done it, you know?

War is bad, but we don’t stop making it. Same with his behavior toward women. He will not learn from the most embarrassing and demeaning things that happen to him. In a way it was playing with truth, because this guy doesn’t recognize truth, even if it’s right in front of him. Other books are largely tragic, in the sense that they’re somber and pretty grim. This book, because of the Clinton thing, made me want to write a comedy and laugh at what is really not very laughable stuff.

BELL

When you were talking about the Battle of Hastings and history, I was reminded of July, July and how we have all these different characters from a class. Were you trying to create a history of the class of ’69?

O’BRIEN

I was trying to create a different take on the same stuff-different people responding to the same central phenomena. There’s a war in progress, and so many people are full of idealism. How do we respond to the same things? And the characters are different aspects of my own personality. Sometimes I’d be Billy going to Winnipeg, and other times I’d be David Todd going to Vietnam and living with the crippling, debilitating, corrosive effects afterward, the way he did. Other times, I’d be Amy, living in the world of a marriage gone sour.

The idealism is crippled for all of these characters in different ways- what they aspire to wasn’t always shattered, but it was diminished for everybody in the book. It’s meant to be, in part, a story of a generation. I was part of that romanticism and naiveté and the high ideals. This is a generation to stop war, hit the streets, and not just change war, but change male-female relations and make them more equal and fonder. Those expectations were ground away by what happened to these people, the way my own idealism was ground away by Vietnam. I became cynical, skeptical of political leadership and my fellow man. It’s not only the political leadership, but also the old lady in Dubuque who’s voting for another war without any thought, but doesn’t want her son in it: “Anybody else’s kid, but not mine,” the way Bush’s two daughters weren’t sent off to war and so on. To see that hypocrisy repeated again and again makes you cynical.

EDMONDS

What’s your take on the situation in Libya?

O’BRIEN

There’s this ambivalence that hits me. A part of me thinks, God, Gadhafi is a tyrant and he’s evil; he tortures people and he should be tossed out on his ear. A lot of people in his own country think so. Then another part of me thinks, Man, we’ve tried that before-doing other people’s work for them, and it doesn’t always turn out the way we want. As in, say, Vietnam.

The noblest of ideals can turn sour and backfire. Nobody appointed the United States policeman of the world and arbiter of conflicts: We’re going to step in and get rid of this tyrant and that tyrant. We could be at war with three quarters of the world right now, for the same reasons. Overthrowing despots. You could be at war everywhere. Is that what we want? Do people have a right to determine their own destinies, or are we supposed to step in?

So I’m ambivalent. Part of me thinks, I don’t like that guy. And part of me thinks, Man, that could be really dangerous. In the end, I don’t trust principle. I don’t trust generalizations. I mean, I have to ask myself basic questions. For example, would I want my kids to go die over there to get rid of that guy? Do I feel that strongly about it? I try to make it personal. Would I want to lose my life for that? Is it worth it? And sometimes the answer is, Yeah, it probably would be. Say, a World War II situation. Other times, I’m not so sure. Say, Vietnam.

WALLETTE

I wonder if you could talk about how your stories arise or develop.

O’BRIEN

It varies by book and by short story. Sometimes I start with a scrap of language that interests me, and I pursue it. There’s a story in The Things They Carried called “How to Tell a True War Story” and the first line is, “This is true.” Period. Three words. And I wrote those words without knowledge of what was true, what the word “this” referred to, and what the word “true” meant. True in what way? Then I wrote the next two sentences: “I had a buddy in Vietnam. His name was Bob Kiley, but everyone called him Rat.” Period. Right away I knew that the first sentence and next two sentences were in contradiction, because I didn’t have a buddy in Vietnam by the name of Bob Kiley, and there was no Rat. That contradiction intrigued me, because, I guess, it was part of the overall structure of the book-playing with what’s true and challenging that word in every way I could.

But then it was an investigation. The sentences that followed were a way of trying-through a story told in bits and pieces, a collage-to get at what I meant in the first sentence, with “This is true.” What does it mean when you say a thing is “true,” and how do the meanings of the word “true” change through story?

Other stories are born in different ways. An image will come into my head-Cacciato was born that way, those mountains I mentioned. It came from a memory of looking at the mountains and saying to a guy, “God, we could just walk into those mountains, and who’s going to stop us? We can get out of here.” I remember the guy laughing and saying, “You’re out of your mind,” you know, and that was the end of it. But the image of looking at those mountains and saying that was the genesis of a novel.

Some of them begin from overheard conversations. One came out of a letter received in the mail from a woman that made me want to write a story about that letter. They start in all kinds of different ways. One of the things about talking about writing, period, is that it’s so reductive. You pull out a thread and talk about that theme or this, and you feel like you haven’t done service to the whole web of it all: language, character, plot, all that stuff.

EDMONDS

Northern Lights is told from the close perspective of Perry, who is not in the war. What was the dichotomy like in inhabiting Perry, while developing Harvey?

O’BRIEN

We started out by talking about how part of me is the guy that stayed home and didn’t want to go, and didn’t go, who wanted a peaceful life and wanted nothing to do with killing anybody and was slightly in awe of and felt estranged from this other personality that went to the war. To this day, I look skeptically at that other part of my personality who went to war, and I don’t feel like that’s the person you’re looking at here.

TAYLOR

Is that what you were exploring in Lake of the Woods, with Wade’s attempt to sort of magically remove his participation in the massacre?

O’BRIEN

I think we all do little tricks to try to erase our flaws, even from ourselves. We’ll fine tune, and we’ll try as much as we can to forget the bad things we’ve done and wish we hadn’t, and magnify those things we’re proud of. I think our country does it, too, and other countries as well, where we erase what we did. We think of America, the great and the good and the beautiful, and we could talk for an eternity about the Constitution and all that. But you could also talk about slavery and American Indians, Jim Crow laws, Hollywood blacklists. Our country, like other countries, erases, through forgetfulness, the reality of what was and probably still is. When John Wade erases his name from the roles after what happened at the My Lai massacre, he’s doing pretty much what everybody in this country is doing as they eat their lunch. They’ve erased My Lai. Nobody thinks about what their country did-how we once had slaves and once exterminated a whole race of people, the Indians. People don’t think about that stuff. It’s erased.

Certain people really erase it. The Fourth of July types in their speeches, for example: “America the great and the honorable and sacrificial,” and most of them are fellow soldiers in Vietnam who’ve erased it all. It’s all nostalgia and, “Boy, we sacrificed ourselves,” and they walk around in their fatigues that don’t fit anymore over their potbellies. They’ve erased how much they hated it and what a sewer of nastiness it all was. And not just the stuff you’d expect-the killing and the daily firefights-just the daily nastiness of it all: beating up on people and racism and knocking kids around and burning down people’s houses and pissing in their wells and all the nastiness that’s part of even a righteous war, much less one that’s utterly without rectitude.

I find it frustrating to meet veterans. I’ll give a reading or a talk and they’ll come up to me and say, “Thank you for your service,” and my heart just goes to my guts. Oh man, they didn’t hear what I said or they’d know I don’t want to be thanked for it. That would be like telling Ted Bundy, “Thank you for your service.” I feel like I did something bad, and they’re saying, “Thank you.” They didn’t hear what I was talking about. You know you’re not the person they should be saying that to. Say it to somebody who believes in it and wants to hear it, but not to this guy.

So you feel that it’s all futile in a way. I’ll think, What the fuck am I doing, writing these books and going to colleges? It feels like it’s all been a waste when you hear somebody say that to you. It’s as though I’ve been inadequate or they’re deaf-probably a mixture of the two. You go home feeling like, Oh man, I’m not doing this again for a long time, because you feel like you can’t do anything. It feels like after all of these years of trying to write as truly and gracefully and beautifully as I can, I’ve gotten nowhere. And I’m not the only person who’s felt that way. That’s what Vonnegut meant in Slaughterhouse-Five, that line about how you might as well write an anti-glacier book as an anti-war book, wars being as easy to stop as glaciers. I met Mailer late in his life and he had the same sort of thing to say, that he didn’t get anywhere. He smiled at me and said, “And you didn’t either.”

EDMONDS

How’s writing changed for you since you had your sons, Timmy and Tad?

O’BRIEN

I’m writing about being an older dad with two little boys, but the fundamentals are the same. As in Vietnam, where I felt this proximity to death-you’re aware of your mortality when you’re in a war, and the same when you’re old and become a parent. What’s going to become of these boys? Thirty years from now, I’m either going to be really old or dead. Life delivers stuff to you-a war or kids-that makes you viscerally aware of what we’re all aware of intellectually-that we’re going to die. We know that, but we erase it. We don’t want to look at it, and we don’t. But certain things put it in your face. I’m trying to write a book now that takes account of my own mortality and the youth of those kids, the realities of it, but that then tries to do what I did with the books in Vietnam, to salvage something from the inevitable and the ugly, the little stories and the works of art that I hope will be carried not just by my boys when I’m gone, but in other hearts as well. The object, I guess, is to leave behind, both for my children and for other readers, something that we all aspire to, something that’s beautiful in one way or another, a story that does something to our hearts that wouldn’t have been done otherwise.