February 3, 2011

Blake Butler, Samuel Ligon, and Joseph Salvatore

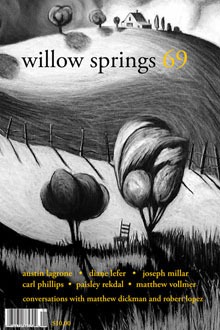

A CONVERSATION WITH ROBERT LOPEZ

Photo Credit: unsaidmagazine.wordpress.com

The fiction of Robert Lopez occurs in a world simultaneously oppressive and hilarious, in which people fail to recognize their spouses or lovers, in which something is wrong but it’s not clear what, in which characters are subjected to a kind of imprisonment they don’t understand and, at first glance, hardly seem to care about. But they do care; throughout the work, characters demonstrate a deep, subtle resistance to the restrictions of their lives and relationships and institutional affiliations or entrapments-a resistance coupled with an inability to master forces in a world they can’t begin to understand. Often noted for his distinctive voice and style, Lopez creates worlds and characters we somehow at once recognize and yet have never seen before, arising from language and cadences that compel like a kind of beautiful, weird song.

Robert Lopez was born in Brooklyn, New York and raised on Long Island. He’s the author of two novels, Part of the World and Kamby Bolongo Mean River, and, most recently, a book of stories called Asunder. The Faster Times notes that “the Lopez syntax has evolved over the years to become both recognizable and utterly unique in its uncompromising approach. Language may be a dull instrument, but it’s the best we’ve got; lucky for us, Lopez is up to the challenge.” The Review of Contemporary Fiction refers to his prose as “like a great jazz performance : pointedly provisional, even damaged, and solicitous of audience participation.”

Lopez’s stories have appeared in Bomb, the Threepenny Review, New England Review, Willow Springs, Norton’s Sudden Fiction Latino, and many other places. He’s taught at Columbia University and William Paterson University, and he currently teaches at The New School, Pratt Institute, and Pine Manor College’s Solstice Low-Residency MFA Program. He’s been a fiction fellow of the New York Foundation for the Arts, as well as a visiting writer at the Vermont Studio Center. He edits No News Today, a blog, or running anthology of dispatches from a deep pool of writers, including Roy Kesey, Amelia Gray, Terese Svoboda, Jess Walter, and Nelly Reifler, to name but a few.

We met with Mr. Lopez at the Omni Shoreham hotel in Washington DC, where we talked about logic and connective threads, damage and its aftermath, repetition and refrain, knowing and not knowing, and how, as a writer, “you have to cultivate your fears, your perversions, your peccadilloes, your compulsions.”

BLAKE BUTLER

Throughout your work there’s a balance between knowing and not knowing, revealing and not revealing. Your characters seem at once unaware of their social function and hyper aware of it. Is this a product of you, the writer, not knowing what you’re going to write as you’re writing?

ROBERT LOPEZ

I’m always most interested in not knowing. That’s my default. To me, there’s authority in that ignorance, because I know that my narrators and characters don’t know anything and I know that they’re aware that they don’t know. I also know that it’s frustrating as hell to them, but that they, on some level, accept it. They want connection with people, but they know that connection is never going to happen.

JOSEPH SALVATORE

They want connection so badly they can’t do it right?

LOPEZ

They don’t know how to do it right.

SAMUEL LIGON

What makes a story feel complete to you?

LOPEZ

By the time you get to the end of a piece of fiction, I think you should feel that you’ve been someplace, that you’ve had an experience. Somewhere I read John Turturro saying, when asked how he played a character: “Well, what you saw is what I did. I can’t really go beyond chat.” Similarly, for me, the way a story works is how it works. It’s an intuitive thing. I might feel, Okay, here’s the end. But that doesn’t mean I necessarily know how my fiction works, or that I want to demystify it.

I do have a sense of how short stories work structurally and formally, though I can’t say I understand the workings of long fiction, even though I’ve written two novels. There are probably ten failed stories I cannibalized for Part of the World. Same thing with Kamby Bolongo Mean River. I cannibalize what doesn’t totally succeed in its original context but chat has something good or interesting, some language or a situation, and I use chat. The fragmentation leads to something that starts to feel complete. I like what Donald Barchelme said about college-something like “Fragments are the only form I use.” I work with fragments because it’s the only way I know how to work when I put together something long.

BUTLER

Some of the linchpins for your characters are their feelings of comfort when they recall memories from childhood, particularly in Kamby. All else-the concrete reality around the narrator-seems somehow chimerical.

LOPEZ

And what’s funny to me is that I don’t find anything particularly sustaining in memory. The present always beats the hell out of anything we may have done in the past. Same goes for the people in my past people I loved. Memory is flawed, hazy, and therefore unsatisfying. So it’s funny that to the narrators or characters in my fiction, memory is the only thing that’s reliable or real.

LIGON

What’s the driving force of Kamby?

LOPEZ

The character is static-he’s confined. But he wants out. It’s his desire to escape that’s the driving force, unlike, for example, Beckett’s character in Molloy, who’s in this bed, in this room. He doesn’t want to be anywhere else. He’s accepting of where he is and what he’s doing. He’s telling his story; he’s going to cell it now, tell it one more time, etc. Whereas, the narrator of Kamby wants the hell out of that place, but he doesn’t know how to achieve the escape. That’s where chose suicide attempts come in-if they are suicide attempts. But if he were to get out, I don’t think he would be able to survive.

LIGON

What’s wrong with him?

LOPEZ

I have no idea.

SALVATORE

You’ve said that you write in a state of not knowing, and that, after the writing is over, you remain uncertain of what you’ve done and maybe even why you’ve done it. One could say that your books enact that same not knowing. So, not only are the characters and the reader kept in the dark, but the writer keeps himself in the dark, too?

LOPEZ

That’s exactly right.

SALVATORE

So you’re totally resisting the old Fiction 101, which is that you should know your characters’ predilections and preferences- what color sheets he sleeps in, which cereal she buys, whether his wristwatch is digital or has a face. This is the stuff we’re told we’re supposed to know, even though cereal and wristwatches are never mentioned in the story.

LOPEZ

Exactly. For example, there’s no mention of the parents of the narrator in Part of the World, and I have no idea about them-who they were, how they brought him up. It never occurred to me. The truth is, to me there’s no such thing as character. There’s no such thing as story. Or plot. All we have are words arranged on a page. It’s on the reader to make character. There’s no such thing as a Holden Caulfield. Somehow readers experience and feel like they know this character, but there is no real character.

SALVATORE

But language has to signify something. Plot exists because the writer chooses to construct language to make meaningful articulations that move in a particular direction. We can’t just say that words are empty signifiers.

LOPEZ

Of course they’re not empty signifiers, because then you could put any words in any order. In the Raethke poem, “My Papa’s Waltz,” the words are in a very specific order. Half of the poem’s readers think it’s about child abuse, the other half think it’s a father and son horsing around. Does it matter what Roethke’s intent was? No, it’s up to the reader to decide. As a writer, I’m going to do what I have to do to keep myself engaged. I hope I’m going to keep a few readers engaged along the way. And then, what you make out of it is what you make out of it.

LIGON

In Kamby, the reader does get deep context for the narrator’s life. We end up knowing a lot about him. Why do you show us what you show us in Kamby?

LOPEZ

I never think about what needs to- well no, that’s a lie- I do think about what needs to go into a story to compel the reader. I love what VS. Prichett said: ”A short story is something glimpsed out of the corner of the eye in passing.” I’ve always held onto that. And not just for a short story, but also for a novel. Obviously a novel has to be fuller; it has to be a different experience. But you can cultivate the “not knowing” part of that fullness. And so, what’s left out of Kamby and what’s left out of Part of the World is as important as what’s put in.

The narrator in Kamby talks about his injury, and then he mentions a place called Injury, Alaska. Now, is Injury, Alaska a real place? I have no idea, but he claims to have grown up there. Some of his claims are kind of ridiculous because, obviously, there’s no place in Alaska where they need air conditioning. So is he intentionally fucking around with the reader? I don’t think he’s intentionally trying to be duplicitous.

Unlike many writers, place really doesn’t interest me. Which is why Part of the World doesn’t “take place” anywhere. Kamby might take place in Alaska, or it might not. Very few of my short stories even mention place. And none of these people have jobs-at least that are mentioned. The jobs of the characters don’t interest me. What does interest me in, say, Kamby, is what is revealed about the character through his memories and his feelings about those memories. Whether it’s Charlie being a boxer, or his mother being kind of an abusive deadbeat. But my intention is not to explain why he’s where he is or how he got in that situation.

BUTLER

All of these things we’re talking about-the traditional elements of fiction-are play-toys for what’s really the magic of your writing, which is the logic. In your novella, The Trees Underground, we watch a character’s logic evolve by bouncing back and forth between orchestrations of place, person, and memory. In Kamby, when the character remembers what his brother used to do to him, it isn’t as interesting as him trying to figure out why he remembers that and who exactly that guy was. And it’s logical; it’s like math without anything following the equals sign. How do you use what I’m calling logic as a tool in your writing?

LOPEZ

It’s a great question and it really resonates with me. How do writers create transitions in narrative? My approach is to pick out something that’s come before the time in which the story takes place. I try to create a connective thread. So it’s just a matter of finding out what those threads are and which of those threads interest me. The narrator of Kamby might mention something that his current tormentors are doing to him; and that’s going to catapult him into talking about the time he was with Charlie and they were out early one morning sneaking out of the house or whatever. I couldn’t possibly work without that logical progression from point to point. Maybe I rely too heavily on it.

BUTLER

But that’s where the emotion is for me, because that’s how life feels.

LOPEZ

And that emotion is: How the fuck did I get here.

The narrator of The Trees Underground finds himself someplace and has no idea how he got there. But he’s there and he’s responsible for people who need his help. He doesn’t know what qualifies him to do any of the things he’s doing, yet he has to do them. He’s also hoping to get the hell out of there, just like in Kamby Bolongo. But unlike in Kamby, he has responsibilities. Both narrators find themselves mysteriously confined to a place. Both narrators feel a certain impotence because they have no real free will; they can’t leave for some reason or another.

SALVATORE

And in Trees Underground it becomes a question of, Does he really have these responsibilities, or is this something they do to keep him busy because he’s annoying?

LOPEZ

Yeah, it could be that as well. Absolutely. And I don’t know the answer.

LIGON

Is the logic logical? Is it rational?

SALVATORE

It’s logical to the narrator in the moment he’s in. It’s like a dementia patient. You watch them and in the moment they’re convinced-“This is this way and that is that way”-and the next minute, they’re almost a different person. “No-that’s not how it is.” And it continues to change because something’s wrong with their brain. It’s true now, and it’s true now, and now it’s not true, but it’ll be true again.

LOPEZ

Most of us can connect, maybe, to these narrators or characters to a degree, but not completely. The narrator of The Trees Underground is kind of extreme-dull-witted and totally befuddled by what he’s doing and who these people are, and he doesn’t understand very fundamental things. I think this rubs up against what we know of the world and how we move around the world and feel like we can give the appearance that we’re competent. We’re holding it together to an extent.

LIGON

Does fiction need damage to work?

LOPEZ

I think we’re born damaged. I think we’re marked at birth. You know, you come out of there and they slap your ass, and it’s already traumatic. And immediately you’re thrust into coping mode. As Larkin so famously said: Your parents, they fuck you up. And then our schools fuck us up. So, yes, I find damaged characters, damaged narrators to be the most compelling kind. But they have to be human at the same time.

BUTLER

The damage is always off the page. We don’t know what the hell is wrong with a character, as though we’re getting the aftermath.

LOPEZ

It’s always the aftermath-when they’re taking baby steps toward something that resembles recovery. For the people in my fiction, it’s baby steps all the way through, across tenuous ground. They’re trying to make it across somehow, without getting more damaged along the way.

BUTLER

You use a lot of diched language and repetition and something that almost feels like sampling. Characters repeat things they’ve heard. But you’re not really quoting it; you’re sticking it into the rest of their speech. It’s like they’re dinging to these meaningless ways of speaking.

SALVATORE

Yeah-the characters skew a cliche that reveals some kind of mystery in the story. And then the form enacts it by this recursive-what might be called repetition, but I’m thinking more like Gertrude Stein’s recursion where when we return to either a phrase or a sec piece, it’s slightly skewed again. Is that a strategy you practice?

LOPEZ

We all know the experience of deja-vu, like, I’ve done this before. I play with that experience in Part of the World-places and events and thoughts and language occur and reoccur. I use borrowed language to illuminate something and to create tension. In Part of the World, the narrator is totally unaware that he’s ripping off Nabakov or Proust or Wallace Stevens. Sometimes he’s doing it verbatim, and sometimes he’s fucking around with the text. But he has no idea, because he doesn’t know what’s his and what isn’t. He can’t distinguish a thought that might be original from something that he read or that someone said to him. He appropriates what another character says to him the same way he appropriates Beckett or Shakespeare. He doesn’t know what belongs to him.

LIGON

The repetition makes your sentences and word choices feel extremely deliberate. Your teacher, Amy Hempel, has been referred to as a “line writer.” Are you a line writer?

LOPEZ

I think there are certainly line writers, who produce work in which the line becomes the dominant experience of reading, as opposed to work that’s all about story or narrative. You could say Alice Munro is a narrative writer. But Updike, to me, was a line writer. Those sentences are put together in a way that seems much more sophisticated than, say, Alice Munro’s.

Music was a big part of my experience growing up, and as a teenager I started singing and playing guitar. I’m into the ways that music works structurally, and this informs my use of language and line. Repetition is key in music-the refrain is a vital element. If you take refrain out of music then the whole thing can fall apart.

LIGON

Is there risk in too much focus on line?

LOPEZ

There can be, certainly. And sometimes risks work out and sometimes they don’t. Sometimes a writer’s prose is so dense that a reader isn’t able to extract any emotion. The language can be meticulous; the lines, the sentences, can be perfect. But one can’t get any feeling out of it. I’ve read well regarded work that has left me feeling cold- not cold as in the chill of fear-I mean cold as in flat-lined: books that are perfectly constructed, but I couldn’t draw a visceral response from the work. Language-wise they might be perfect, but I need something more. The language can’t be-for me, for my sensibility-it has to work for me. Like Gertrude Stein said, there has to be a “there there.”

SALVATORE

It’s interesting that you talk about the need for emotion, and Stein’s “there there” in light of your strategy of cultivating ignorance and not providing characters with jobs, places, and in some cases, past history. You’ve said you want compelling-

LOPEZ

It has to be entertaining.

SALVATORE

So, on the one hand you don’t want to know too much about what’s going on behind the curtain of your fiction. And yet you actually, think, you’re a craftsperson whose more conscious of a craft than he’s admitting. And who, as a reader, responds to the very craft elements that he feigns ignorance of. This is what it seems to me Blake was saying about characters making him feel human feelings. I’m wondering if, when you talk about creating compelling work, you’re not simply talking about plain old plot?

LOPEZ

Ah, God. I have no idea. I mean, for me- it’s like the Supreme Court’s definition of pornography. I can’t define it, but I know it when I see it. I know it when I do it.

Sometimes whatever it is that we’re calling “compelling” happens in the initial composition, and a lot of times it happens in the revision. For instance, in Part of the World it happened solely in revision, because in the very, very first draft, absolutely nothing compelling happened. I was playing with the tenets of the nouveau roman, trying to get rid of everything to see what was left. But then, going over it, I thought, Okay, you need something to happen. So, that sense of a “there there” definitely happened in revision with Part of the World.

LIGON

What bores you as a reader?

LOPEZ

Again, it’s similar to the Supreme Court thing. For instance, each of you goes about creating a story in an entirely different way, but when I read your work, I feel there’s a heat that’s generated. On occasion, I pick up The Night in Question, by Tobias Wolff, and every semester I teach “Bullet in the Brain.” Bue I recently picked up Back in the World and I read all the first lines, and they just weren’t as dynamic as his other first lines. Writers are cold, “The whole story has to be in the first line.” What bores me is the overly familiar, the pedestrian.

SALVATORE

If we apply that logic, “Call me Ishmael” would probably not pass-

LOPEZ

No, no, “Call me Ishmael” certainly does. There’s something arresting about “Call me Ishmael.” Is that not your name? Who are you? What else would we call you? That, to me, is a brilliant opening.

SALVATORE

Amy Hempel used to say that she couldn’t write past one line if that line wasn’t working. Is it that way for you with the first line of a story or novel?

LOPEZ

Every piece I’ve written-the novels, stories, or the play I just finished-comes from a single line. They never come from an idea or an image or an experience; they come from one single line. And the next line pushes off the previous line. In Kamby, that line is “Should the phone ring I will answer it.” I like the contingency of that. There’s power and powerlessness in that line. “Should the phone ring,” which is totally outside my control, “I will answer it.”

SALVATORE

The theorist Gilles Deleuze, in writing about Melville’s Bartleby, says that the comical is always literal. It can’t be metaphorized because of the way it works in Melville, the syntactic queerness of “I would prefer not to,” a linguistic formula that is the story’s “glory” and which “every loving reader repeats.” He talks about different kinds of humor, including works by Kleist, Dostoevsky, Kafka, Beckett. Do you see yourself as a part of this lineage? It’s a humanizing kind of humor, in a certain way.

LOPEZ

I saw this really good movie recently- Winter’s Bone. It was entirely humorless. Now, you can do a dark, dark movie, and I respond to darkness. But God damn it, have some laughs along the way. That was my major problem with that picture- there wasn’t one chuckle or light moment or even a dark funny thing; there was nothing funny at all. When that happens, it’s one note and no matter how compelling it is I don’t respond the way I’d like to respond. I’m not saying I want something to be jokey, like Dave Barry in the Miami Herald or something.

BUTLER

I think there are two kinds of humor: inside and outside. Your characters tell jokes about things they think are supposed to be funny, or that they really think are funny, which makes their shitty world a little better. But then, there’s the humor where you’re looking at this guy who’s keeping track of which way his erections go, left or right. And he’s not joking . The scariest moments are when I see your characters doing things I do myself. I’ll be reading about something a character does and I realize that I do that and I’m like, “Oh my fucking God!” Because everyone does those things in different ways.

LOPEZ

I tell students that you have to cultivate your fears, your perversions, your peccadilloes, your compulsions. You have to use that stuff because it’s ultimately going to make the work vibrant and come off the page. All the stories we tell have been told a million times before. Nobody’s going to come up with a new story. It’s all the same old thing; somebody is losing something, somebody wants something, somebody is afraid of losing something, somebody is afraid of wanting something. We can’t not write those stories. We cultivate the strange things that make us unique, and that uniqueness is what connects us to other people. Otherwise strangeness is just a freak-show. Like what you see on Jerry Springer.

BUTLER

You’ve said you don’t know how to write a novel, though you’ve written two novels, you don’t think of yourself as a novelist. Do you consider your novels to be very long short stories?

LOPEZ

No, I think they’re novels. But when I think of a novelist, I think of someone who sits down and writes novels. John Updike is a novelist, Anne Tyler is a novelist. I do consider myself a writer, but as often as not, I feel like it’s almost always a happy accident every time one of these things comes together- whether it is a one-page story or a novel; like it was almost the luck of some sort of draw.

BUTLER

The last lines of “Monkey in the Middle” are, “I’ve come to realize that what goes on when I’m not around is none of my business. Mostly.” If it feels like luck to you, why do you keep doing it?

LOPEZ

Because it gives me something that nothing else does, and because it’s what I can do. When it’s working, it’s such a satisfying feeling. And, you know, it’s nice to have the books on the shelf. You can look at them and say, “I did that,” although I rarely do this. At any rate, there’s a line in the Wallace Stevens poem, “The Planet on the Table:” ”Ariel was glad he had written his poems. They were of a remembered time/Or of something seen that he liked.” And then later in the poem, there’s this: “Some affluence, if only half-perceived,/In the poverty of their words.” The desire to make something that wasn’t there before motivates me.

There’s a magic when a line comes and you put another line behind it. I remember Stanley Elkin saying something like-at this point he was in a wheelchair-“Well, I might not be much physically, but on the page, I’m a god.” When we write, we can be gods. Though, of course, our readers don’t think of us as gods. Kamby certainly has some detractors a few people have voiced their disappointment about that book.

LIGON

What do they want that they’re not getting? Plot?

LOPEZ

I imagine. But they can go to a million other writers for that. It’s none of my business. I wouldn’t know plot if it knocked me in the-

BUTLER

But you’re a huge movie lover. And plot is a major part of movies, particularly certain kinds of movies that I know you like, like The Godfather. So what’s the difference between telling a story in image and writing a script?

LOPEZ

When you do something visually you have the instrument of the actor who communicates so much without using language-without resorting to the base thing chat language is. One of my favorite moments in film is the brilliant Anthony Hopkins in The Remains of the Day. He’s in his parlor, right? And he’s the most uptight character you’re ever going to come across-entirely introverted and withdrawn, scared of human contact. He’s in his parlor, he’s in his safe place, and he’s reading a book, and a woman he’s attracted to, played by Emma Thompson, invades his space. She wants to know what he’s reading; she’s curious. “What are you reading? Just tell me what you’re reading.” But he doesn’t want to tell her. By not wanting to show her the book, he’s saying, “This is my private time and you’re invading it. I want to be alone.” He’s holding the book to his chest, but she’s insistent; she’s moving in on him, which he is not inviting at all. She’s caking the book physically from his hands. And the heat that Hopkins has in his eyes, of repression-he wants her, he’s extremely attracted to her, but he doesn’t know how to go about the next human move. He can’t negotiate it; he can’t handle it; he can’t express it, certainly. But Hopkins somehow manages to communicate all of that without language. It’s all here; it’s all in his face.

That’s what film can do. And I can think of other moments. The end of Big Night is one of my favorite moments in film. The brothers have had this argument, it was horrible, and you think they’re now estranged. You think, This is it, they have to go their separate ways. The very next morning they’re exhausted, they’ve had this big night and there’s a scene entirely without dialogue that goes on for minutes. It’s extraordinary. Stanley Tucci makes eggs for himself and then for his brother, played by Tony Shalhoub. The whole scene is like a silent movie at this point. That’s the kind of thing that when we write fiction we just can’t do. And in film, I want to know what’s going to happen-I expect to know. I require plot. Whereas, in fiction, I don’t require that at all.

LIGON

You have a deep emotional response to the ending of Big Night. Can you talk about a similar response you’ve had to fiction?

LOPEZ

You know, it’s funny. I’ve almost never had- I’m not quite our new Speaker of the House where I can cry on a dime, but I can get emotional. I can be emotional. Music has moved me that way many times, film has moved me that way. That hasn’t happened in a long time with film, though. But there have been times with film where I’ve either felt leveled in the seat, where I can’t move, or I’ve been moved to tears. I have never been moved to tears, except for one time, with reading. And it wasn’t fiction, it was nonfiction. It was Andre Dubus in Broken Vessels. There’s an essay in that book that moved me to tears. But for fiction, I’m neither-it’s a different feeling. It’s visceral because I do feel stirred somehow. I feel compelled, I feel entertained, but somehow it’s a different kind of emotional connection. Maybe it’s because it’s the thing that I do. I don’t know.

LIGON

Do you get as much pleasure from it today as-

LOPEZ

Not even close.

SALVATORE

In what, reading or writing?

LOPEZ

Reading. I read to my friends, and I get pleasure out of that, but there was a time when-if a new book by a writer I admired was coming out, I was there that Tuesday getting it. And that doesn’t happen anymore. I think I’ve been over saturated. I teach four workshops a semester. That means I’m reading critically all the time. So even if I read somebody I consider a friend and who I like-not even a close friend where I want to read everything, but a casual good friend and I want to support them-I pick up the book, because I’m supporting it and I’m reading them, and I like their writing. But I go for a little bit, and then it’s as if I say, Okay, I’ve got a sense of that, and I put it down. It always feels like I’m on the job.

BUTLER

The pleasure factor has diminished for me, too. I don’t necessarily feel on the job, but I feel the pulling away. Each year I feel a little less pleasure, reading and writing.

LOPEZ

I remember feeling it was a magical experience to get a new book. Magical.

SALVATORE

What are some of those magical books you couldn’t wait to buy? And what are you drawn to today?

LOPEZ

These days, there are no authors other than my friends that I’m excited about. Because it seems I’ve already seen what’s being done. There’s nothing new for me there, which I know is bullshit, but whatever. And the books that I loved in the past- well, I picked up I Sailed with Magellan recently, and I remember the first time I read “We Didn’t”-it was in the nineties-and that story knocked me on my ass. I thought it was one of the greatest things I’d ever read. It lived in my memory as a brilliant, brilliant story. But when I recently picked up I Sailed with Magellan and reread “We Didn’t,” it just wasn’t happening for me.

That story is the same, but I’ve changed and now the story doesn’t work for me. I lament the change. I’ve become too ruthless as a reader. If there’s a line, if there’s a clause that explains too much or feels too commonplace, I can’t abide it and I stop. But I did read The Coast of Chicago recently and totally dug it. I didn’t have a single moment where I thought, “Well, whatever.” But looking at I Sailed with Magellan, I’ve been trying that and it just hasn’t happened for me. And I don’t know exactly why.

SALVATORE

Your work, it seems to me, is influenced by David Markson and Samuel Beckett. Would you talk a bit about those influences or others?

LOPEZ

I’ve said this before, but reading Hemingway’s ”A Clean, Well Lighted Place” many years ago made me want to write a story. So I wrote a story or two. I had no instruction, I wasn’t an English major. I took lit classes in college, but didn’t pay attention in them, so I never did the work. I actually paid for the papers I handed in. The way I was taught literature in high school and college was to look for symbols and memorize and extract interpretive meaning that was concrete. We would read a poem and say, “What’s the poet really saying?”

What’s the poet really saying? The poet said what’s on the page.

SALVATORE

But poets do talk about how hard they’ve worked on a metaphor, and to make a particular, very aestheticized event for the reader, right? So poets are thinking about it.

LOPEZ

And that’s poetry I’m not interested in. I read Wallace Stevens. I love Wallace Stevens. I don’t want to know that he’s trying for metaphor, because to me, he’s not. To me, he’s putting language down that has metaphor. To me-and I tell this to my students all the time-it’s like acting. You want to feel the anger, you don’t want to show the anger. If you feel the anger as an actor, the anger will come out. But if you’re crying to play anger, you’re going to be overacting. If a writer is trying to be true to whatever he or she is putting down on the page, the metaphor is going to happen. It has to happen, because everything. I mean, we don’t live in a bubble. We don’t live in a vacuum. Everything is contingent upon something else. Everything is related to something else. So metaphor is inevitable. It arises. It cannot not happen. So, when people say, “I’m trying for a metaphor, I need a metaphor,” I think it’s the wrong way to go about it. It gets heavy-handed. It makes the reader say, “You’re not trusting me as the reader to get it, and so you have to hit me over the head with it.”

LIGON

You mentioned Hemingway-

LOPEZ

Hemingway made me want to read. When I came across Carver, he made me want to be a writer. Not just write a story, but make a life out of this activity. There was something about the power and mystery of chose stories. Every one, at the end, had a punch in the gut. I felt like I’d been someplace. I felt I’d experienced something. And I had an emotional, visceral connection to it, along the lines of “Ballad of a Thin Man;” something has happened here but you don’t know what it is. And I was totally fine with not knowing what it is.

But when I came to read Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress, and the fragmented way that was put together, I said, “Okay, fragments. That’s something I can move around in.” And so that worked with me and that sparked something in me. And also, Beckett’s Molloy-where he strips everything down, and gets rid of so much. I like what Faulkner said in his Nobel acceptance speech, ”All literature is the human heart in conflict with itself.” And, to me, I try to distill that down to someone in a room-How did I get here? How do I get out of here? How do I make connections with other people? There are feelings of isolation. And disappointment. Beckett and Markson handle that on a language level and a narrative strategy level that moved me and opened up my head to what could be done on the page.

LIGON

In contrast to some of the bleakness of the worlds you create, are you a romantic? Your characters are so often disappointed, like: “It shouldn’t be this way. We’re damaged and it shouldn’t be this way.” There’s something innocent and romantic in that view.

LOPEZ

I’ve never thought of it in those terms, but I think you’re right. I mean, I think all of my narrators believe that life shouldn’t always be this hard. This is how it is, but it shouldn’t be this way. And almost like Jesus on the cross: “Why have I been forsaken, oh Lord? Why me? Why have I been forsaken?” But then, also: They get through somehow. Somehow, they get through.