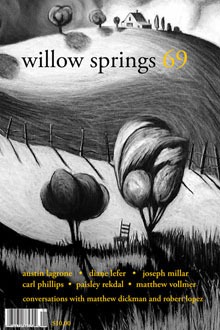

April 15, 2011

TIM GREENUP, KRISTINA MCDONALD, DANIEL SHUTT

A CONVERSATION WITH MATHEW DICKMAN

Photo Credit: Academy of American Poets

It’s difficult to read a Matthew Dickman poem and not uncover some essential nugget of humanity. His debut collection, Alt-American Poem, charts a wavering world of involved pleasures and intense dramas, where any experience is worth mining, be it a morning trip to die farmers’ market or ruminations on suicide.

While acutely aware of grief, his poems never become steeped in it, and his readers never feel bombarded by it. His voice is a companionable one: funny, warm, profane, yet always springing from some place of incense longing to connect with others, in spite of often violent or bewildering circumstances. Dickman’s drive for communion is refreshingly proactive, as he searches, sometimes manically, for any semblance of hope he can find, such as in “Slow Dance,” when he arrives at a place of sobering clarity:

There is no one to save us

because there is no need to be saved.

I’ve hurt you. I’ve loved you. I’ve mowed

the front yard.

Dickman is also a master of die sensorium. So rich are his poems in sights, smells, sounds, tastes, and textures, reading them is like eating a full Thanksgiving spread with your best friend, men curling up by the fireplace together to listen to all your favorite records. Tony Hoagland, in his intro to All-American Poem, says, “We turn loose such powers into our culture so that delay can provoke the rest of us into saying everything in our minds. They use the bribery of imagination to convince us of the benefits of liberty.” For such art to exist, we are all for fortunate.

Calling Dickman’s rise to literary fame a “rags to riches story” wouldn’t be entirely accurate (when is it ever?) but one might call it “a rags to nicer rags story.” In 2008, when he won the Honickman First Book Prize for All-American Poem, Dickman was thirty-four and working at Whole Foods in Portland, Oregon. That Same Year, All-American Poem won the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ May Sarton Poetry Prize and, in 2009, the Kate Tufts Discovery Award and the Stafford/ Hall Award for Poetry.

Add a New Yorker profile and fellowships from The Fine Arts Work Center in Province town and the Vermont Studio Center, and Dickman seems a literary wunderkind. The man himself lacks all pretension though. During our interview at the Northern Lights Brewery in Spokane, he poured the beer, sporting a faded hoodie, a pair of thirty dollar blue jeans, and some beat up sneakers. He was in town for the 13″‘ annual Get Lit! festival, and talked with us about growing up in Portland, his relationship with Dorianne Laux, surrendering to influence, the importance of empathy, and what it’s like being famous.

TIM GREENUP

Let’s start from the beginning. How long has poetry been in your life and how have you nurtured it to where you are today?

MATTHEW DICKMAN

I fell in love with an older girl in high school who liked poems, so I started reading poems and writing bad versions of them to give to her in hopes she would make out with me or take her shirt off. I failed miserably at that part of it. But I started reading Anne Sexton and other poets, and Anne Sexton totally blew my mind. I’d never read poems like hers. In high school, we were reading Donne and Shakespeare, which were great, but not very exciting for a high school boy. Sexton led to others-Plath and Lowell and later Wachowski- and my reading life sort of took off, and I continued to write poems as well.

I grew up in a very healthy single-mom home in a pretty shitty neighborhood. No one was really hanging out reading poems. It was kind of a private thing, but it was also a way for me to deal with what was happening in my neighborhood with my friends: violence, drug abuse and things like that, also, sort of, something to have that was just mine. When I went into community college to start what ended up being my six-year undergraduate program, I got interested in the Beat poets, and I remember seeing a photo of Ginsberg, Kerouac, Neal Cassady, and all of these people standing on a corner outside City Lights bookstore. And I thought, This is amazing-a group of men standing together on a corner, and they’re not going to hurt anybody. Because, in my neighborhood, if I was walking home and there was a group of men on a corner, you’d want to walk around that corner. Something was going to happen or something had just happened. They certainly weren’t talking about beatific, angelic powers. I thought it was amazing that you could be a guy- you could be a man-and you could be humane and compassionate. You could be an artist, but you look at Neal Cassady and he’s still wearing jeans and a tight shirt. Not that I could ever pull that off.

I also had my twin brother, Michael, who is a great poet he and I started sharing poems. I ended up finishing school at the University of Oregon. I had gone there because Dorianne Laux taught there. But I never took a class from her. I went there, Michael, me and Dorianne all befriended each other- and then I worked as Dorianne’s personal assistant for a while. We would just hang out and talk about poems and write together.

GREENUP

How did you befriend Dorianne Laux? Is she just an approachable lady?

DICKMAN

I think all poets are. It’s poetry. It’s not like being able to approach a cobbler. “God, he makes really great shoes. He really knows how to fix a Birkenstock. Let’s not talk to him.” My brother and I found out Dorianne was teaching at the University of Oregon in Eugene, and we were living in Portland. It seemed really, really close and we were huge fans. So we called and lied to her. We called the university and said we wanted to talk to Professor Laux about an MFA program that we wanted to attend. We set up a meeting, which my brother and I thought was crazy. We couldn’t believe we could just call her office. We got into the only car we’ve ever owned- his station wagon-and cruised down. We went into her office and started talking and, of course, within ten minutes, she could tell we were full of shit, that we were nowhere near approaching an MFA program, but we did talk for an hour about poets we loved, and we wrote her when we got back to Portland and said, “Thank you so much for your time” and she was very sweet and wrote us back. We started writing back and forth.

I always tell people to do that. I have friendships with poets I never would have had if I hadn’t reached out in some way. And it was never like, “Hey, I really like your poems, do you think you’d write me a recommendation?” It was always like, “When my brother died, I read this poem of yours for months afterwards.” Or, “I’m pretty sure that this poem you wrote made it possible for me to have sex with this woman that I really liked.”

So if you reach out to poets and say, “Hey, your work has meant a lot to me; I think it’s awesome,” most people will write you back. If you connect as human beings, then you might have a mentor relationship, or you might have a friendship relationship, and I think that’s really, really important. Sometimes with schools, and different coasts, and different cities, we get into this thing where we feel like we can’t reach out, or we’re embroiled in our own scene. But poets, even the most “famous,” don’t get a lot of letters saying, “Your work meant something to me.”

DANIELLE SHUTT

Do you consciously bring that passion or drive to be in touch to your poetry?

DICKMAN

I think community is really important. I like that people have different communities. I think the danger is when you start only identifying with one community. Then you have things like the East Coast/West Coast rap wars. In my poems, I’m certainly writing out of my own life, and hopefully in some way it’s with a heart that tries to be inclusive. I want that in my relationships too. I have friends that barely read poems and I have friends that that’s all they do. I have blue-collar friends and I have friends who have earned millions of dollars. Bur I think we all have something in common. I’m also kind of a romantic, I think. And kind of naive.

DICKMAN

The immediate audience is always just me. It would be baffling to sit down and write a poem in a way that I would think, Okay, this poem needs to reach this certain person. I would not have the first idea how to do that. In fact, one of my fears is that my second book will come out and people will read it and be like, This is just Matthew talking. Why buy the book?

So I’m my audience, first and foremost, and then, after that, I don’t really imagine anybody in particular. I mean, I want my poems to be read by people. I don’t think any acting troupe ever rehearses a play for months to not put it on stage. And I love it when people read one of my poems and they’re affected by it. In kind of a base way, I’m happy if they’re affected, regardless of whether they like it or not. If they just fucking hate it and think it’s the worse, it’s something. The worst response would be, like, “Eh, it’s a thing.” I know there are people who like my poems and people who don’t, so I feel lucky in that combination.

I used to have rules for myself when I was writing, and ideas about whom I was writing for. However a poem gets written is great, but I used to write poems and do a lot of research first. Like, project-poems. And these poems were in stanzas, and pretty squared off. And then, right after my first year of graduate school, I had what some people refer to as a “mental breakdown.” A son of psychic break. I had to take a little time off, and during that time, I decided that I was not going to worry about poems.

I used to worry about them a lot before this happened. If I didn’t write within two or three days, I’d imagine I was experiencing this thing that people called “writer’s block.”

But during this time of getting my brain and my heart right, I decided l wouldn’t deal with it. I would read poems when I wanted to, but I wouldn’t write any. So I didn’t write poems for eight months or so. And then I went back to school and thought, Well, if I can’t write poems anymore, poetry will still be part of my life. It has changed my life, it has molded my life. I thought about doing something cool like a lit review, or running a reading series, or something awesome like that.

But I started writing again. Those poems ended up being like my poems in All-American Poem. No stanzas, no idea in my head before sitting down, just sort of an emotional feeling, like I needed to get something out. Like the poem “V.” I walked by this girl in Austin who was wearing a shirt that said, “Talk nerdy to me,” and I thought it was

SHUTT

Do you see empathy as the ultimate responsibility in what you’re writing about?

DICKMAN

I think empathy is one of the greatest things besides love. Empathy is in love; it’s a part of it. But empathy is the most important thing a human being can do. And I don’t ever, when I’m making a poem, set out to be empathetic. But I think the world is so scary, and in my experience it’s been, sometimes, so wildly violent, that’s my desire- my hope, and where my imagination goes–for there to be at least a strand of empathy there.

You know, making art and experiencing art are both pretty radical, because, in the end, art is about humanization, empathy, and even trust. I think everything can make art-heartbreak, erotic love, familial love, jealousy, headiness. All of these different attributes of human beings can make art. There are only two things that can’t make it, and those are meanness and violence. They can’t sustain themselves, because they-like some creature from Greek mythology-eat themselves and crap themselves out, eat themselves and crap themselves out. There are no moments of exploration, no moments of epiphany in meanness, like there are even in pettiness. I think that’s the only way that things are somehow ruled. You can do so much more out of empathy and love than you can ever accomplish out of meanness or violence.

You can create art looking at chosen things, but you can’t create art out of them. I have a friend who was a neo- Nazi for seven or eight years, and we’ve recently reconnected. He has not been involved in that gang for fourteen years now, but he writes about his experience. His prose about it is moving and terrifying and empathetic and complicated. He could never have done that when he was a neo-Nazi. He could never have created art that could sustain itself out of that.

KRISTINA MCDONALD

Your poems never feel like they’re excluding anyone. I’m curious who you consider your ideal audience. Do you think about that when you’re writing?

DICKMAN

The immediate audience is always just me. It would be baffling to sit down and write a poem in a way that I would think, Okay, this poem needs to reach this certain person. I would not have the first idea how to do that. In fact, one of my fears is that my second book will come out and people will read it and be like, This is just Mathew talking. Why buy the book?

So I’m my audience, first and foremost, and then after that, I don’t really imagine anybody in particular. I mean, I want my poems to be read by people. I don’t think any acting troupe rehearses a play for months to not put it on stage. And I love when people read one of my poems and they’re affected by it. In kind of a base way, I’m happy if they’re affected, regardless of whether they like it or not. If they just fucking hate it and think its the worse, it’s something. The worst response would be, like, “Eh, it’s a thing.” I know there are people who like my poems and people who don’t, so I feel lucky in that combination.

I used to have rules for myself when I was writing, and ideas about whom I was writing for. However a people gets written is great, but I used to write poems and do a lot of research first. Like, project-poems. And these poems were in stanzas, and pretty squared off. And then, right at my first year of graduate school, I had what some people refer to as a “mental breakdown.” A sort of psychic break. I had to take a little time off, and during that time, I decided that I was not going to worry about poems.

I used to worry about them a lot before this happened. If I didn’t write within two or three days, I’d imagine I was experiencing this thing that people call “writers block.” But during this time of getting my brain right and my heart right, I decided I wouldn’t deal with it. I would read poems when I wanted to, but I wouldn’t write poems for eight months or so. And then I went back to school and thought, Well, if I can’t write poems anymore, poetry will still be a part of my life, it has molded my life. I thought about doing something cool like a lit review, or running a reading series, or something awesome like that.

But I started writing again. Those poems ended up being like the poems in All-American Poem. No stanzas, no idea in my head before sitting down, just sort of an emotional feeling, like I needed to get something out. Like the poem in “V.” I walked by this girl in Austin who was wearing a shirt that said, “Talk nerdy to me,” and thought it was a great shirt. It was was common, but it was also more than that, because I went home and there was something bothering me about the shirt. Something that seemed to be resonating. I sat down and wrote the first couple lines, where this girl walks by wearing this shirt that says, “Blah blah blah.” No idea where I was going. It was like colorful building blocks, sort of being stacked one on top of another.

GREENUP

It’s interesting to hear you say you were working in stanzas and tighter lines, because, just looking through All-American Poem, there’s such freedom in how your poems are constructed. Is that really just a response to your mental state? Like you were one way for a while and you felt constricted by air, and once you broke free it was like, I’m never going back; I just want my lines to do whatever they want?

DICKMAN

I felt that way not just in my writing, but in my life. So, before I went to therapy, I felt that there were parts of my life I was constricting and not dealing with, and I was not as free as I could be. Which is not very free at all, for any of us. So I think it was a reaction to that, but it wasn’t very conscious. It was only after I had been writing like that for a couple months that I realized, This is actually fucking fun. I’m not suffering over the page as much. I might be suffering about what I’m writing about, but not how I’m writing it. I think you can trace that impulse back to the fact that I was a really poor student. It’s like somebody saying, “Well, I don’t do essays. Or paragraphs. I don’t figure out this thing that’s actually very fascinating.” I think stanzas, line breaks-you know, these things are interesting and powerful in molding a poem and your experience of a poem. But I’m horrible with line breaks and, for me, when I’m making a poem, I’m interested in the things that stanza breaks and sometimes smart line breaks don’t concern themselves with- the experience.

SHUTT

When do you get a sense that a poem is coming to its end?

DICKMAN

Sometimes it’s just instinct, like an exhale. Sometimes the exhale is short and sometimes it’s long and sometimes you can write a poem and it sort of naturally comes to the end and it just feels right. It’s like if you ask, “Why are you and this person together?” No one says, “Well, here’s the list of things that make us lit together. “You’re just like, “It feels good.” But, also, I’m a true believer in redraft and rewriting. I once asked Jorie Graham: “How Do you know a poem is finished?” I was particularly interested in a couple of her poems that were sort of listy and went on for a long time, because I’m kind of a listy, blabby, poet too. And that can go on forever. If it’s a bad date-how do you stop it so it’s a good date? She said, “If you’re unsure about the last line, you should write another fifty to a hundred lines.”

The instinct in workshops is often to cut stuff, which is natural, but sometimes unhealthy. Her suggestion might be rough if you’re writing a ten-line poem, but I think what she’s talking about, really, is to go beyond further. You’re not going to keep all of it, but you might figure out something about the poem with that kind of writing.

Sometimes, I’m having a rough time with a poem, I’ll read it and then turn it over and immediately type it up without looking at it. It’s not so much an exercise in memory; the point isn’t to read the poem, turn it over, and remember the whole thing. But you read it and you get a close sense of it, and if you try to write it again, new things will come out. What’s happening, I think, is that the conscious part of your brain is busy trying to remember the poem, and since you’ve got your conscious over in the corner being busy, your subconscious can come out and have more freedom. Other things will come up. And then I print it and look at them side by side. Maybe it’s a failure. Fine. But maybe, scuff that’s come up in this new draft looks better than the old one, or maybe the old one and the new one together makes you think about something else, which could lead to a better ending to the poem or a better beginning.

GREENUP

In an interview on Bookworm with Michael Silverblatt, you were talking about how you’ll read someone like Jorie Graham, someone who’s sort of heady and cerebral, and you’ll think, Why aren’t I writing chosen types of poems? But then, when you sit down to the page, it’s like, you do what you do. I feel like sometimes we put pressure on ourselves-at least I do-to become like, Oh, how can I be headier? or, How can I shatter the world a little more?

DICKMAN

I think we shatter the world in our own way. Jorie Graham Applied to be Jorie Graham. It’s no shock that if I applied to be Jorie Graham, and Jorie Graham applied to be Jorie Graham, she would get the job. I might be shortlisted for the work, but I wouldn’t get it, which is fine. But I think that’s a healthy reaction; it also means you’re a reader. You’re reading something beyond what you write, which is so intensely important.

When I came back to grad school from my waylay, something I started doing, which I never would have done consciously- I started imitating people I liked. Like, really closely imitating them. I remember reading a ton of Lucille Clifton. She’s amazing. And I started writing these Lucille Clifton kind of poems. They were short. I was trying to find these bright, hyper-energetic of crystalline images. A lot of poems were about my own mother’s bout with breast cancer. So, you know, sometimes the subjects sort of overlapped. I would do that for a while, and then I’d pick up someone else and start interacting them. I never sent out any of those poems to get published. I was just digging on them. And it was actually more exercise as a reader than as a writer, because in attempting to mimic them, I got closer to the language that I was reading. And even though each one was a type of failure, it was at least a failure in the left field of the same stadium that this person was in. Whoever said you should be cautious of in influence, or afraid of influence, is just wrong. We are influenced by so many things. If you’re afraid of influence, then don’t ever watch TV, don’t read anything, certainly don’t talk to anybody- I mean it’s a path of insanity to try to

not be influenced.

GREENUP

You’re observant of everything and it’s like, I see this, I’ll Follow it. I feel this, I’ll follow it. I smell this, I’ll follow it. Is there anywhere you haven’t gone that you’d like co go?

DICKMAN

The new book I’m working on is called Mayakovsky’s Revolver. Vladimir Mayakovsky was a revolutionary Russian poet who shot himself. There are rumors that the KGB killed him, but most of his friends believe he committed suicide. This book is called that partly because its center is a group of elegies for my older brother, who also committed suicide. Some moments are about friends of mine who died that way. I’m delving into a place I never went to in All-American Poem, which is this idea of the Shadow- the Shadow being, obviously, the shadowy, darker part of ourselves. We present ourselves like, I’m not going to kill you. But depending on the circumstances, who knows? We’re all nice people. I’m nice, we’re all nice together, but we have this shadowy, dark stuff. I wanted to explore some of that in an artistic way. There are a couple poems in the book that come out of almost exact personal experience. Like “An Elegy to Goldfish,” about killing my sister’s fish, and then chasing her around with a piece of an orange, telling her it was the dead goldfish and making her eat it. And then, another experience when I was younger: telling a very inappropriate joke in what my grandmother would call “mixed company,” and that joke being something that had happened to one of the people in the “mixed company.” And also, not just particular experiences of the Shadow, but also what’s emotionally of the Shadow, like my own failures and things like that. I mean, talk about multitudes: our failures

as well as our great moments of empathy.

MCDONALD

Is there anything you consider off-limits, something that doesn’t belong in a poem?

DICKMAN

If you consider separating areas, like writing a poem, into the spiritual world and the secular world, then in the spiritual world I don’t think anything is off-limits. In the secular world, there might be limits. You might have something you wrote about your grandmother or your boyfriend that you don’t want to publish while they’re alive. Or you might say, “Fuck it, it’s my life. I’m going to publish it.” Larry Levis once said in a poem, “Out here, I can say anything,” and when I heard that, it was this amazing moment about freedom, because we’re not free people, except when we’re making art. That’s the only moment when we’re truly free, the only moment when we’re the people with the key to the lock. I don’t think anything should be cast out as far as subject matter in a poem, though, or how you write a poem, or what you want to include in a poem. I mean, fuck, we’re going to die.

GREENUP

Would you talk a little about your whirlwind rise to poetry fame, because it all seemed so fast- winning the American Poetry Review first book prize and being profiled with your brother in the New Yorker. What was that like?

DICKMAN

Well, it was weird, because I had been part of this group of poets, and still am-me and my twin brother and my friend Carl and my friend Mike. My brother had this string of successes where he’d gotten poems in American Poetry Review, and I got a rejection. Then he got into the New Yorker, and then he got his book taken by Copper Canyon. And after that, Mike won the Starrett Prize, which is the first book prize for the Pitt Poetry Series.

Carl and I were like, “Well, can’t happen for everybody.” You know what I mean? We’re close friends, we all share our writing, we’ve shared it for thirteen years and I sent out to a bunch of book contests and to a couple publishers that were interested though the book I sent them was very different from this one. And they all said no.

Then I sent some more poems off to APR and I got an e-mail, and they were like “Hey, we want to publish these two poems you sent us.” I was fucking stoked. Like, American Poetry Review, which is huge. It felt great. In my e-mail back to them, I said, “I’ve done a couple redrafts on one of the poems that I’d love to send you, and you CU1 publish either version.

A week later, I got a phone message from Eliwbeth Scanlon at APR who’s a wonderful lady. She was like, “Hey, this is Elizabeth at APR Give me a call back.” I thought she was calling because I e-mailed her the redraft of the poem. I called her and she said, “Matthew, we are your new favorite literary review.” And J was like, “Oh, great, yeah. You guys are awesome.” And she said, “Do you know why I called you?” And I said, “Yeah,about the redraft I sent you.” And she said, “No, you just won the Honickman First Book Prize.” I was so shocked, I was like, “Get the fuck out.”

I got off the phone and ran down the stairs screaming and called my brother. From the time I found out to three days after-at least three days-I felt on top of the world. And then, after many months, I got the book in the mail. It didn’t feel like a real book. It felt like something I’d made at Costco, if Costco had a printing press. A Couple days later, I picked it up again and it looked like a real book. But just because it had my name on it, it didn’t seem real to me. A while after that it felt normal, and it was awesome and continues to be awesome.

The New Yorker profile interviews happened right before I got the book in the mail. So the interviews were conducted between finding out I’d won a book prize, and the book being printed. Then it came out, I got an e-mail from a friend of mine- a kind of “big deal” poet in New York- who was like, “So, how does it feel to be famous?” I told her this true story. I was working at Whole Foods in Portland and had recently moved from the dish room- where I’d started as a thirty-four-year-old- to the deli, where I’d just gotten done with this dinner rush of assholes who were really, super rude. That’s the sad tiling; I hadn’t done customer service in a long time and sort of thought we were really brave, just to be human. But then, working the sandwich/pizza lines at Whole Foods, dealing with people’s rudeness was amazing to me. And disheartening. I was sort of broken after the rush, standing there in my uniform, in my apron, covered in pizza sauce and flour, looking out the sliding glass doors at the little lights coming through the Portland sky. The cash registers were right there in my view, and there were all these magazines at the cash registers and the person who always came to switch out the magazines walked into my view. He took the old New Yorker off, and put the new New Yorker on that had this big profile of my brother and me. And then he left. I was at the pizza island, staring at it, thinking, This is life. You know? This is life. You’re working the shitty job, paying rent, but then , sometimes, something incredible happens. And so I wrote my friend about this. I was like, This is what it’s like to be famous.