February 20 & March 16 , 2010

Gabe Ehrnwald, Samuel Ligon, Brendan Lynaugh, and Shawn Vestal

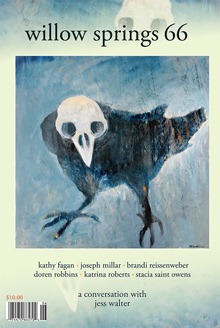

A CONVERSATION WITH JESS WALTER

Photo Credit: thelitupshow.com

JESS WALTER FOLLOWED A CONVOLUTED PATH into the literary mainstream: He was a newspaper reporter who became a nonfiction author who became a ghostwriter who became a mystery novelist who became a literary novelist who also writes screenplays. But no matter the genre, Walter’s work is stamped with vivid watermarks—prose that blends rapid-fire rants with unerring rhythm, a dark humor that has been called “standup tragedy,” an engagement with the political and social, and a devotion to storytelling. “The idea that plot is this ugly, brutish thing that we have to drape our beauty over is infuriating,” he says, “because to me, plot is this beautiful, elegant shape.”

His essays, short fiction, criticism, and journalism have appeared in Details, Playboy, Willow Springs, Newsweek, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the Boston Globe, and elsewhere. His nonfiction book, Every Knee Shall Bow, was a finalist for the PEN Center West literary nonfiction award in 1996. His novel Citizen Vince won a 2006 Edgar Allan Poe award, and his following novel, The Zero, was a finalist for the 2006 National Book Award.

Walter started his career writing for his hometown newspaper, the Spokesman-Review, where he helped cover the standoff between Randy Weaver and federal agents at Ruby Ridge, in North Idaho—work that eventually led to the publication of Every Knee Shall Bow in 1996. His first novel, Over Tumbled Graves, came out in 2001, followed by The Land of the Blind, Citizen Vince, The Zero, and most recently, The Financial Lives of the Poets, which Time magazine called “a small masterpiece, a Wodehouse-level comic performance. But it’s also a deceptively amusing survey of the post-Fannie-and-Freddie American landscape, with a mother lode of bitter truths lying right below its perfect, manicured lawns.”

We spoke with Walter over two meetings at Spokane’s Davenport Hotel, which features prominently in The Land of the Blind. “It’s taken me a long time,” Walter said, “to arrive at a place where I feel like I’m doing the work I set out to do.”

SAMUEL LIGON

How has your writing career evolved or developed since your start as a journalist?

JESS WALTER

It’s evolved accidentally, the way natural selection works in making platypuses. If you decided to become a literary writer by going into journalism and then ghostwriting and then writing mysteries, that’s the worst path you could take. I like to say I’ve taken the service entrance into literary fiction.

I started at the newspaper in 1986 as a junior in college. When Ruby Ridge happened in 1992, I started sending out proposals right away and I took sabbaticals from the newspaper to work on that book. Later, my publisher asked if I wanted to help write Chris Darden’s book on the O.J. Simpson trial. I was compelled by Darden’s Shakespearean angst. I teased him about it later, and called him “Black Hamlet” because I didn’t understand what he was so anxious about.

My publisher at the time said, “Would you be interested in helping him write his book?” In my naiveté, I didn’t even know there was such a thing as ghostwriting. I knew it existed, but I didn’t realize it was an industry, so when she asked me to help him, I just assumed we were going to write it together. We sat down to negotiate, and I didn’t have an agent at the time. I sat across from his agent, his lawyer, and Chris, and they have this contract that says I’m ghostwriting, and I said, “I’m not doing this if my name’s not on the book.” They were like, “How big do you want your name?” I said, “I want my mom to see it from outside a bookstore window.” So that was the agreement, and then there was discussion about what the cover would say—“By Christopher Darden, as told to,” or “By Christopher Darden with”—and I said, “I don’t care about that. I just think it’s a lie to not have my name on the cover.”

Later, when I would do ghostwriting projects—I didn’t want my name on a book once I realized the stigma, and once it became clear to me that ghostwriting was not what I wanted to do. But that was the first ghost job, the Darden book, and again, it wasn’t strictly a ghost project, because my name’s on it. And also, this was a really intelligent guy, and I said, “We’re going to write this book together.” So we had two laptops, and we’d write sentences back and forth. It was collaborative. I moved in with him. And I feel…everything’s accidental, nothing’s planned, but I look at that early part of my career, the ghostwriting, which began with Darden and ended with the Bernard Kerik situation placing me at Ground Zero. I’ve got Ruby Ridge, the O.J. Simpson case, the terrorist attacks of September 11th. I kind of had a perfect fiction writer’s vantage to these cases that, for someone who loves satire and writing about the culture, turned out to be perfect training. It’s not the training I’d advise someone to undertake, and I was miserable through much of it, but it turned out to be a great track to the kind of fiction I wanted to write.

LIGON

How have your books changed from Every Knee Shall Bow to The Financial Lives of the Poets?

WALTER

Each book I write is a kind of reaction to the last one. It’s a constant leveling and adjustment to try to make each book complete and full in itself. When you’re in a book, you’re not thinking about the next one or the last one, you’re only thinking about the one you’re in, but you bring the way the last one felt. My starting point is often, The last one felt like this, now I need to do that. Especially Over Tumbled Graves—I was stunned that everyone saw it as a mystery novel. I look back now and see that’s because it was a mystery novel. You put a serial killer in your book, people tend to treat it like a serial killer book. You eat one lousy foot, they call you a cannibal. But at the time I was writing it, I thought I was writing this deep literary novel that happened to have serial killers and cops in it. And then when it came out, that wasn’t the response. So, with Land of the Blind I thought, Well, I’ll nudge it over a little further. And with Citizen Vince, I think I was a little aware of the way these books were landing, the way they were received, the way they were perceived, the way they were put into bookstores.

There are all sorts of indignities along the way that cause you to do certain things. I remember I was excited to have a reading at Powell’s, this amazing bookstore. I told some friends to meet me there. I didn’t really think that two o’clock in the afternoon was a funny time for a reading at Powell’s. So my friends show up and I walk to the desk and say, “I’m Jess Walter, I have a reading here.” The woman at the counter says, “Oh, that’s a drop-in signing. What’s your book about?” And I said, “Well, it’s a kind of literary crime novel about a serial killer—” I didn’t even finish and she grabs the microphone and says, “Genre department.” This guy comes forward and my friends are standing right there and I’m thinking, Oh, this sucks!

LIGON

Can you talk about the difference between “literary” fiction and “genre” fiction?

WALTER

I’ve often felt frustrated at the divide between commercial and literary fiction, because to me, it hurts both. You can have this horrible writing in crime fiction because people only focus on plots, and they treat them like crossword puzzles. “Well, I knew who the killer was on page eleven! I’ve solved it! Why do I need to keep reading?” And when people complain about literary fiction, they say there’s not enough story. So I’ve always felt like there’s got to be some sweet spot in the middle you can hit. With Land of the Blind, I thought, Oh, I’m writing a coming of age novel, and I’m kind of melding it with this other thing, and it’s also a novel of ideas! You have all the conventions of crime fiction that I wasn’t following. There was no murder. It starts with a confession instead of the body, which is where you start with a murder mystery. I wanted someone to come in and confess to a crime that hasn’t actually been committed. And then it was a kind of twenty-five-year-long murder that began when they were children—it’s really about the way he treated this guy as a kid. So it was, in my mind, a coming-of-age novel disguised. Again, you hit what you think is some sweet spot and no one wants it. People really want crime fiction and they love those books. You mess with the conventions, they don’t understand why. I was making Subaru Brats—you know those little Subarus that were a cross between a pickup and a car? Nobody wanted those or there would be a bunch of them around today. And I made a great Subaru Brat, but I was the only one who appreciated it.

LIGON

Do you think anybody succeeds in that kind of hybrid?

WALTER

I think Richard Price comes closest. Once he established his literary bona fides he could write crime fiction. Pete Dexter, because he won the National Book Award, can write a crime novel and have his position. John Banville wins a Booker Prize and can go write crime fiction. But it doesn’t work the other way. You can’t name someone who’s made a career as a crime writer who is then respected as a literary novelist.

SHAWN VESTAL

But after you won the Edgar for Citizen Vince, the next book, The Zero, was a finalist for the National Book Award.

WALTER

When I say no one’s done it, I kind of think I’m the only one. [Laughs.] And I don’t know that most people want to do that. It’s one of those Guinness Book of World Records things that no one else really wants to do. You stand on your head on a toilet for four years and you’ve done it longer than anyone else. It’s not a path a lot of people want to take.

BRENDAN LYNAUGH

Citizen Vince felt like more than a crime novel. Were you aware that you were turning a corner?

WALTER

It felt like the kind of novel I wanted to be writing. I get really excited about thematic elements, probably more than I should, and more than most writers. I kept thinking, This is really about voting. That was the sweet spot I had always imagined between crime fiction and literary fiction—you know, that I could create characters that were hopefully deep and rich. There would be all these ideas swirling around, especially in the character Vince and in his monologues. I like ranting and riffing, and Vince could do that in a voice I was pleased with, and yet, I could still drape it over the conventions of a crime novel. I think it was more the sort of novel I’d imagined I would write all along. And it does feel like I turned a corner at that point. And then I moved on to The Zero and Financial Lives of the Poets.

LYNAUGH

You’ve mentioned having to teach yourself how to write a novel. Can you remember big moments in that process?

WALTER

I still feel like I’m teaching myself all the time, learning things and in a constant conversation with myself about what it is. The emotions of writing a novel, the highs and lows, the ups and downs, the loathing for what you’ve written—I described it in my journal at one point as the diary of a man living on the ocean who has no idea what tides are. “Oh my God, the water’s going out! It’s a drought! Oh my God, the water’s coming in! It’s a flood!” I couldn’t believe how seriously I took this. With every book I would say, “If this is not the worst thing ever written… I need to just throw this away and start from scratch.” And then the next day, I would say, “I may be writing a new kind of literature here. There’s a very good chance that my grandchildren will have to study this book. I should put a little note in there for them.” The grandiosity was stunning, and the lows were stunning, too.

I think of it as this engine, these pistons going up and down. The process that I fool myself with is that I write the last sentence last, and so I’ll comb over the beginning so many times, but I can’t finish if I feel like there’s something wrong early on. I always have to go back and rewrite things. The moment I finish a novel, I always feel the same incredible high. My finishes are phony at first. I always have to go back through dozens of times, but that sense, when I write the last sentence and pull my hands away or clap my hands like a Vegas dealer, it’s thrilling. And then maybe a week later, or two days later, the crashing doubt comes back. I’ve learned now that I love almost every part of that journey. I even love the self-loathing. I think to separate the hypercritical self-loathing writer from the one who dreams of doing something beyond his ability is impossible and probably not even worthwhile. I don’t think you could have one without the other.

I just read David Shields’ new book Reality Hunger and now my debate and argument with myself is also with him. I’m constantly walking around, saying, “Well, take that, David Shields!” or “What about this, David Shields?” Which is great—to have a foil. But that book was remarkable and vexing in so many ways. I found myself walking around arguing with him, which is such a pointless thing to do. It reminded me of some drunk guy on the dorm floor you’re trying to argue with and he just keeps quoting Pink Floyd. You can’t win that argument. And other times, it reminded me of arguing with a girlfriend, because you say, “Well, clearly this, this, and this,” and she says, “But that’s just how I feel.” You can’t win that, either.

But it makes me want to debate those points, because I think it’s a really compelling case, a great read, and really powerful work. Because it’s a manifesto, it wants to make a case, and it’s a case I would certainly argue with. First, that narrative is dead, and that there’s some supplanting of it by a desire for reality. I think the reality that we’re really desiring is far more narrative-driven than he’s letting on. We don’t really want reality. We want reality set in a certain narrative frame. What we really want is the Elephant Man. We want freak show. Reality tv is not like the lyric essay, which is the thing he’s arguing for. It’s like the Elephant Man. It’s the freakiest stuff you can imagine. That’s what we want to see on YouTube—glimpses of the freakish.

I find it illustrative that A Million Little Pieces was rejected as a novel, because you couldn’t get away with that shit in fiction, but you can, oddly enough, in this kind of hybrid nonfiction thing. So there’s the idea that fiction and nonfiction have blended in a way. That because history is subjective, that because memoirs only come from memory, because journalism has been proven to be imperfect, there should be no filter between fiction and nonfiction, which I find to be almost insane, almost a kind of academic trick in which you point to a swamp and say, “Look, therefore there is no land, nor water. They are only the same thing.” And you get there through some sort of “if or then” dialogue with yourself, and pretty soon, you’re trying to drive a boat through the desert. You can’t do that.

Just because there are places where there’s swampland doesn’t mean that there isn’t a desire and need and higher form for nonfiction and fiction. So that’s the argument I walk around having. Zadie Smith wrote about Reality Hunger—something like, “All right, Mr. Shields, read better fiction. You’re right. There’s a lot that’s dead with fiction. Now go read the good stuff, because those manipulations and tired conventions are exactly what good fiction tries to overcome and subvert and not fall victim to.”

LIGON

You suggested that nonfiction can get away with stuff that fiction can’t. Like what?

WALTER

What was Tom Wolfe’s famous pronouncement? That fiction can’t keep up with the real world? I think fiction has the responsibility of a kind of universality that nonfiction doesn’t. A good example is Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn. His portrayal of Tourette’s is—to anyone who has nervous habits or tics or things—so real that it immediately takes you inside that condition. It’s brilliant for that. It isn’t just someone with Tourette’s spouting dirty words, which is what the reality television version would be. It’s a human portrayal of this thing that may be freakish to people who don’t have it, but through Lethem’s telling is a fully realized and human condition that we relate to.

LIGON

You mentioned two North Korean pieces the other day, one fiction, one nonfiction. What could the nonfiction deliver that the fiction couldn’t?

WALTER

The first thing that pops into my head that the nonfiction delivered was context. Both pieces had to do with the period of starvation in North Korea. Both had people making this sort of paste from tree bark that they would eat. In some ways, the nonfiction was more harrowing for its authority, for its truth, I guess. It provided context. I found out how many people starved to death during this period. And the nonfiction piece was structured almost like a short story, which is really interesting, because it was not a big societal piece. It was focused on one woman who had been a party believer and whose husband and mother and one of her children had starved to death. She’d finally made her way into South Korea. And it was a narrative of these people starving to death, with the context that this was happening to the entire nation, the politics behind it, the seamless way in which those externalities could be brought in and not break you out of the illusion of the piece. You could come in and out of narrative and pure informative reporting, and I think when fiction does that—one good example is The Known World—it can be thrilling, but it’s also a really tricky thing. It’s an innovation of voice that when I see it, I’m kind of thrilled. That’s what this nonfiction piece was able to do.

The great thing about it, the thing I would probably agree with David Shields about, is that it did not require a movement at the end. It did not require some artful ending. It just ended. The woman went to South Korea. She lived with her daughter and she put on a bunch of weight. There didn’t need to be one last scene in which she goes out to the woods and strips some tree bark and takes it home because she’s acquired a taste for it. It was able to sort of just play itself out.

The short story (which hasn’t been published yet but is forthcoming in Playboy) by Adam Johnson was about an orphan in the same time period, who kidnaps Japanese tourists and brings them back to North Korea—kind of sanctioned by the army. The story is full of starvations, full of all this stuff, and the movement of it, the artful movement is really pleasing and yet you’re aware that that’s where it’s going. When it finishes, you have the sense of release of a story. You’ve been taken to this world and then released from it. And you’ve seen a full movement of character. You’ve seen something that wasn’t required in the nonfiction piece, a reckoning or a surprise or some other narrative turn; the stone was carved into a figure. And I think we know those effects and we know those feelings that we expect to get from both, and maybe that’s what Shields finds so thrilling about the hybrid style that he’s working in. To confuse those effects, to fire off these neurons when you expected those to be fired off, that’s what every fiction writer hopes to do—to not give you what you expect, but something that’s satisfying in some way and which you didn’t see coming.

LIGON

Do you think that the nonfiction was about a phenomenon that occurred in North Korea and something systemic to North Korea, and the fiction was about a person?

WALTER

It’s funny, because the nonfiction was about a person, and this person was used to illustrate a condition within North Korea. And so the person was almost a way of viewing the larger context, whereas in the short story, the context was backdrop at most, or was a way to sort of narrow down on that person. You know the world you’re in. You’re in North Korea. It’s this period of hardship and starvation and that telescopes down on the individual, whereas the other one opens up the world that way. I do think those are both intriguing shapes and that they do very different things. Thank God for both.

LYNAUGH

Often in your books, the main character has some sort of disability— the blindness in The Zero, and various characters in other books who can’t sleep the entire story. What does disability do for your novels?

WALTER

I think everybody has some disability. I think that’s the condition of being human. What happens when they’re more visible, more on the surface? You’re definitely putting pressure on. That’s what I like about crime in fiction. I like conflict that’s sharper and higher-pitched. And I like that within—I think it’s another kind of conflict, a conflict within the character, and the way in which the world deals with these people and they deal with the world. I guess it’s heightening that stuff.

I got a stick in my eye when I was five and had to train myself to look people in the eye, because when I was a kid I would constantly look down so that other kids wouldn’t make fun of me—so to me, disability is a very real state of humanity that I think we all have in some way. I think I use the vision and eyesight issues because that’s such an elemental and key way in which we deal with each other. I also think it’s probably an autobiographical desire of mine to try to explore this in fiction.

LIGON

In Land of the Blind, Clark lost an eye as a kid. In The Zero, Remy has a problem with detached retinas. How does your experience of getting a stick in the eye when you were a kid move away from autobiography in your work and take on a fictional quality?

WALTER

Autobiography is a tool of the fiction writer. I think that Land of the Blind is all about vision, about how Clark sees himself, how the world sees him. And the gaps within there. You become interested in those things in a really personal way, and then I think the thing to do with fiction is refine that interest, refine that sort of thematic push that you have in something until it takes on some meaning you weren’t aware of. I think you arrive at levels of meaning in fiction that you don’t always reach with memoir, that you might not reach with any other kind of writing because of the process, which forces you to go possibly deeper into character than you would with nonfiction or memoir. I think it forces you to create themes that are even more alive than a memoir would be. We’ve all read those autobiographies by generals or politicians, in which you think, “Were they even around for their own life?” They seem to be describing it as this series of achievements that have no motivations connected to them.

VESTAL

You write about the newspaper industry in The Financial Lives of the Poets. Do you think the decline of journalism’s had an impact on fiction?

WALTER

It’s hard to not focus on the ancillary effects, where the review is going to come from and things like that. I’ve always thought that journalism has been a great training ground for novelists. I would make twenty-seven percent of our novelists go work at a newspaper, because you learn to navigate these systems.

You cover any sort of politics, you cover crime. You begin to see the difference between public and private, the way people show themselves in public and the way they really are. You learn the mechanisms of a culture, how a courtroom works, how a police department works, how an election works. One of the ghost jobs I did involved a political campaign and these political operatives…. I’ve got these characters stowed away. They’re such great characters because they have insight into the hypocrisies that we know are there, but we don’t exactly know how they work. That precision, that journalistic precision, is something. Like Richard Price. He’s very much like a documentarian in that style. He’s in there, in those cop cars, in those projects. He’s working with those social workers, and to hear anyone describe his process, it sounds exactly like immersion journalism. So in that way, I think journalists can be outward-looking in their fiction; I think they can get beyond the limits of their own experience and imagination more freely because of their training.

Also, you write every day. You lose fear of publication. You know how to work on deadlines. But you also get out of yourself as a writer. You write something that is very utilitarian—people use it. It’s sort of disposable. I remember being in MFA workshops and people bringing their stories in and the angst of that room was almost too much for me to bear. They had so much invested and I never felt that.

At a newspaper someone is going to handle your stuff. They’re going to edit it, they’re going to change things. You learn to keep your stories separate from yourself. That’s valuable for a new writer because the fear of publication stops a lot of people from working, the idea that it’s got to be perfect. No journalist goes in thinking that they know everything at the beginning, and yet, today, as a fiction writer, you almost get more attention for your debut novel than the ones after. You’re expected to kind of arrive as this fully formed artist, and I know I wasn’t. It’s taken me a long time to arrive at a place where I feel like I’m doing the work I set out to do. I used to have an editor at the newspaper who would say, “All right, this is beautiful writing here, but you have three adjectives. We’re going to pick one. What’s the best one?” I was constantly pruning and looking for the telling detail.

Also, because of the constraints on space, I think journalists often write better-paced fiction, which is the reason people love crime fiction and other potboilers. It’s not that people have bloodlust. It’s about pacing.

VESTAL

Many of your books have humorous elements. What makes something funny? And how do you use that toward a serious purpose?

WALTER

One of the tics I’m trying to get away from is tending toward things only because they’re funny. A few times, I’ll find myself so in love with something I thought was funny that it takes away from the narrative or it introduces something that strains credulity. Some of the humor in Citizen Vince I’m proudest of is the really quiet stuff. It doesn’t come out of absurdity. It just comes out of small character moments. I guess some of it is absurd, two guys in a witness protection program debating the pizza in town, but that’s also a complaint I’ve heard from every New Yorker who ever moved to Spokane, so it seems weirdly grounded, too. You don’t want anything to be a crutch. Plot has been a crutch for me, suspense has been a crutch for me, and sometimes I think humor is a crutch for me.

LIGON

Plot seems to be one of the hardest things to talk about, and people often ask writers, “Do you know the plot before you go in?” What do you know of the story before you start actually writing words?

WALTER

There’s a fallacy that the story starts when you’re writing words. I walk around with the idea, with the characters, with all of that stuff, until I think I may have a clear sense of what that story is—before I start writing it.

I’m going to digress a little bit. One of the frustrations I have with Shields’ book is that he keeps saying narrative is clearly dead, that clearly no one likes narrative. And it’s like, No! People are reading Dan Brown not because he’s a great prose stylist, but because of the narrative. Story is alive and well. People love it. And it doesn’t even have to be a new story. It can be the same old story. That central premise is totally wrong.

I loved reading Charles Baxter’s essay on rhyming action, because to me, there’s an artistic elegance in plot and story. There’s a sense among some people that there’s been an academic movement away from storytelling. There was a great essay—and I call it great because it was infuriating to me in so many ways—that blamed the Cult of the Sentence for the death of literary fiction, the much talked about death of literary fiction, the idea being that somehow, writers focusing only on the sentence as a unit of beauty and on the writing itself, have divorced themselves from what readers want. I don’t think that’s necessarily the case, but I have heard writers say, “I don’t want any story at all. I just want beautiful language.” And I think, first of all, Bullshit. But second of all, the idea that plot is this ugly, brutish thing that we have to drape our beauty over is infuriating, because to me, plot is this beautiful, elegant shape. And that’s what I get so thrilled about in writing. That’s what I got excited about with Citizen Vince, when I began to see this kind of movement of the character and the way the language and everything would reveal this movement that would take you to this place where you would have a feeling of completion. The plot of that story is inseparable from a kind of motion in which Vince lives in this town. He’s afraid someone has been sent to kill him from New York. So he goes to New York, where he’s assigned to kill the guy he thinks came to kill him. I love that movement.

LYNAUGH

In the plot of Citizen Vince, toward the end, there’s a withholding of Vince’s plan. Did you worry about that being too “devicey”?

WALTER

I love device. When that comes about is when we go in Reagan and Carter’s heads, the day that Vince comes home. If I’m showing those scenes, he’s on an airplane, he’s thinking, Holy crap, now I gotta go kill this guy. Or maybe I won’t. I’ve got a big decision. It would have been so static. The book is third person and there are plenty of other times in which you don’t exactly know what Vince is up to. You don’t exactly know what he’s doing at that card game until he tells Gotti why he’s there. So if it was the first time it had come up, it would have felt far more “devicey” and I probably would have been too embarrassed to do it. But instead, we’re looking at Carter and Reagan, who are doing a sort of thematic dance around what this novel is about, the idea of shadows following each other, and when we get back to Vince, he’s taking action and his thoughts are in the moment.

GABE EHRNWALD

Some readers might feel there’s a kind of withholding in terms of the vote.

WALTER

Who he votes for? Maybe because I initially saw this as a screenplay, I thought of that scene as a camera shot, like the famous tracking shot in Citizen Kane in which the camera rises and rises and rises. It’s one of the longest shots in history. It rises completely out of where Kane is speaking. And so I imagined that same shot when Vince is voting, that you’d be centered over him and you’d be seeing the ballot the way he does and then all of a sudden, the camera rises and rises and rises so you could see the act of voting but you could never see who he voted for. I really did imagine that I turned my head when Vince voted and gave him the same privacy we all get.

LIGON

What does it do for the novel that the reader doesn’t know?

WALTER

If it was just a novel about a guy who became a Republican or Democrat, what would that be worth? It’s about a guy who chooses as his point of redemption, his symbolic redemption, the process of voting, which is a really corny thing, and I knew it was corny the minute I thought of it. Am I really going to write a civic thriller? That’s what it is, a kind of civic thriller, but no one else gets to choose what our own symbols of redemption are. And for Vince, voting is meaningful. On the most basic level, not telling the reader who he votes for connects with a theme of the book, that it’s about this person choosing this thing we all take for granted and maybe see as empty or corny or whatever it is, and around that creating a new identity and allowing himself to change.

LYNAUGH

Can you talk about other devices you’ve used?

WALTER

Fiction writing can feel kind of meek sometimes, and if we’re going to run from device, if we’re going to run from things like that, it’s going to stay meek. Your job is to engage the reader. Sometimes to fool them awhile, sometimes to suspend something that you don’t want them to know for a while. Sometimes it’s to have the action interrupted by an end dash and not tell the reader what happened. Sometimes it’s to write something in the first person. There are all different kinds of tools and techniques and I don’t know what makes them devices. But I like to be playful, and I like inventive styles of writing.

The book that nailed me the hardest in the last few years was David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, which is a Russian nesting doll of a book. It’s a device at its very genetic core and I was thrilled reading it. I loved to see what could be accomplished.

I don’t have some bag of devices. But I certainly am constantly looking for something inventive to do with structure, with voice, with all of those elemental pieces of writing that combine to make the whole. So it might be a large structural thing. It might be a voice thing. It might be something that feels as “devicey” as having the action break at midpoint in The Zero and then having the character discover alongside the reader what’s missing. Which feels more blatantly “devicey,” but opens up the thing in a way that you wouldn’t have gotten if you’d written the novel straight. I think those kinds of formal inventions and devices and gimmicks can sometimes lead you to a place to discover not only what’s possible with the language and the sentences and paragraphs, but also what your story is about, what brought you to this. For me, when it works the way it did in The Zero, there’s not a lot of distance between the formal playfulness and the thematic drive that made me want to do it in the first place.

LIGON

Why is withholding important to fiction? Can withholding ever become cheap?

WALTER

A lot of times, what makes something work is what isn’t there. We know that with language, we know that with character, so why wouldn’t it be the same with story? Why wouldn’t the things that you choose not to put in be those things that kind of open the piece up?

When is it cheap? When you’re honestly assessing your own work and you worry about things, what I worry about is that I’ll sell the farm for a cheap gimmick. One of my favorite novels is Martin Amis’ Time’s Arrow, which occurs in reverse. It’s all gimmick. Does it work? Depends on the reader, but I love the inventiveness of it. And Martin Amis referred to that book in The Information, which is another great novel. In The Information, the novel that the protagonist has just written makes people nauseous and causes them to have strokes. Amis is writing about Time’s Arrow and people’s reaction to it.

You know your weaknesses and strengths as a writer, so I’m probably the worst person in the world to ask when a device becomes cheap, when it overwhelms the thing it’s working on, because I tend to like those. Maybe it’s because I read a great deal and I’m looking for something new and different. But I also think it goes back to the fact that I’m most interested in the elemental things, finding out what exactly makes voice, and then the large things, almost like a scientist. Science is interested in the very tiny and the huge, the universe and the subatomic. So I think that my concern with structure, with the fullness of things, makes me more prone to like those sorts of innovations.

VESTAL

What are the similarities or differences between the Spokane in your books and the real one? Or have you set out to capture the “real” Spokane?

WALTER

I don’t know if William Kennedy said, “I’m going to capture Albany.” You just tell those handful of stories that strike you, and then later, if they end up creating a full sense of a place, I can’t imagine it being anything more than accidental at best, because I never set out to create Spokane. I was a crime reporter, so I think I’ve probably created a much more downtrodden, crime-ridden, nasty-ass place than really exists, and yet, I think it’s a very real version of some of those places, too. The Financial Lives of the Poets is set anywhere, and yet to me, it’s so clearly Spokane. People write to me and say, “I think that 7-11 is right by my house! I live in Santa Monica.” “I think that 7-11 is right across the street, except it’s a Piggly Wiggly here.” So I think there’s probably something universal in what I’m envisioning as Spokane in that book.

VESTAL

Vince makes a brief cameo—uncredited as Vince—in The Financial Lives of the Poets, and it made me wonder if you had a sort of vision of a kind of world behind the immediately present world. Or a kind of network.

WALTER

I think I do, and I think every author kind of does. I don’t mind those things overlapping a little, but in no way do I think of that as some definitive portrait of the city. It’s just the terrain that I happen to be writing about. Usually when I’m done with a book—I don’t, for instance, wonder if anything else happened to Brian Remy from The Zero. Maybe Carolyn Mabry from my first two novels, I think there might be more to talk about there, but for the most part, I don’t feel like characters deserve a second novel. And though some of my characters have reoccurred, they’ve been fringe characters. I think it’s another kind of playfulness that made me sneak Vince in there. And the fact that I don’t call him Vince—because at the end of Citizen Vince he’s sort of gone back and claimed his early identity, which is Marty. But I also liked the wink at myself that ninety-nine percent of readers won’t get. When people do discover it, though—again, we talked about withholding—there’s a kind of withholding. I could have easily made it Vince and made it clear, but when people get it, it’s like this special thing between me and the couple of readers who have noticed it.

LIGON

Does your fiction get anything from the place—Spokane—that it wouldn’t get from a different town, like Tallahassee or Des Moines or Providence?

WALTER

I think Spokane is one of the most isolated cities of its size in the United States, and that its isolation casts a lot of different shadows. I think there’s a sense of isolation here that’s great for fiction. And yet the place doesn’t have an accent. It doesn’t have a special ethnicity. It’s a really general place, but hours from anywhere, which gives it a kind of lab quality. As if you could have any kind of experiment here that you wanted. There’s a lot of film work here now because it has that quality—it could be anywhere. So I think yes and no. Spokane could be Des Moines. It could be Providence. It could be the Lower East Side in certain ways, and yet, I think its isolation allows a lot of different things to happen. In thrillers, you’re constantly trying to get your hero alone, and if you think about it, cops always travel in at least twos, sometimes twelves, and yet, you’ve got to get to a point where your protagonist is alone facing whatever he or she is facing. I think that the isolation from the rest of the world that Spokane has creates story possibilities. You can have guys from the Witness Protection Program show up here and have everything they need. It’s kind of self-contained. Most cities of two or three hundred thousand are not self-contained. Most are outside bigger cities and this is like Pluto. I guess Pluto isn’t a planet anymore. It’s like Neptune, a small, distant planet. It doesn’t have moons. It’s in its own orbit.

EHRNWALD

What’s the difference between writing a screenplay and writing a novel?

WALTER

Screenwriting is so collaborative. It’s not the writer’s medium. It’s a director’s medium and an actor’s medium. So that’s the first thing, the collaboration. Also, form is so important and so is economy. Form and economy are the two things you’re constantly battling, and I sort of equate the formal restrictions to poetry, not that I’m much of a poet myself. But I’ll start writing a poem and it’ll turn into prose because I can’t master the economy or the form. I’ve said before that scripts tend to be more external, more action-driven. They don’t have to be. You can have a voice-driven script. You can have My Dinner with Andre, all dialogue. So it doesn’t have to have action. You could have 110 pages of voice-over. It could all be internal. Didn’t they make Johnny Got His Gun into a movie? I think they did, which takes place entirely inside the mind of someone who has been maimed in battle and is unable to communicate with the outside world. Then it’s done through flashback; you still have to show something on the screen. But practically, they couldn’t be more different forms. I like both. Screenwriting I just don’t take as seriously. I don’t think it’s as hard. I don’t think it’s as interesting. I don’t think it’s as rewarding. I think because it takes someone to animate it and make it live that it is beyond my understanding. I can’t imagine ever being fully satisfied with a screenplay. I like fiction better, as a reader and a writer. I like the process of reading a novel far more than seeing a film.

Because my own fiction has flirted with being adapted and made, I’ve had to kind of come up with a mental divorce between a film and the source material—because they are totally different things. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is one of my favorite novels and one of my favorite films, and they are not the same thing at all. You can’t get that paranoia from the book in the movie. You can’t get the walls, the machinery behind the walls from the novel into the film. You couldn’t get Jack Nicholson into the novel and you shouldn’t try. You couldn’t get Danny DeVito as Martini. Those things are animated by actors.

VESTAL

Were there any trends that you noticed as a judge for the 2008 National Book Award?

WALTER

Another judge told me, “You’ll be stunned by how many good books you read and how few great ones.” And I think that’s probably true of any year you judge. There’s a ton of very good fiction out there, but I finished most of the books with some sense of their failing. And their failing was not necessarily the author’s fault. The thing that comes to every writer as they start to finish something is that they’ve begun an imperfect journey. I don’t think any book is perfect and sometimes things are more interesting because of the imperfections.

The other thing you’ll hear people say sometimes: “Why isn’t anyone writing realism?” or, “Why did postmodernism die?” or, “Why isn’t anyone doing this or that?” And the thing I realized is that everyone is doing everything. I found examples of every literary trend you could imagine. Are we finding our way to those books? Are publishers getting behind those books? Are those books reaching wider audiences? No. But someone was trying almost everything. There were some small things that I noticed, like books with titled chapters. There were a lot of linked story collections. It’s hard to tell what’s driven by the writers and what’s driven by the marketplace, such as it exists. It may be publishers saying, “We need more linked stories.” The collections that I thought worked best, though, often weren’t linked. Those collections that were linked felt like bland novels or you’d make a game of saying, “All right, which story did they write to try to link this together?”

VESTAL

A lot of your work involves an individual with some kind of fraught relationship with a system. Did your work on Ruby Ridge in any way set that course?

WALTER

I think my whole life as a reporter was geared toward seeing how systems fail us. You look at the systems we love—just the people at this table—we love universities and they’re in a kind of spiral of failure right now that is epic in scale. We love newspapers and they’re dying out from under us. We love literature and it’s not healthy at all. I love movies and that system’s falling apart. It isn’t just the criminal justice system, it isn’t just the government. The kind of systems that we create to take care of us and to take care of the things we care about and love always break down and fail, almost inevitably. You build the machine and the machine is going to fall apart. The thing I always go back to in my fiction is that these systems, in a way, don’t even exist. They’re powered by people’s insecurities, emotions, greed. One example is New York politics. It’s a huge interworking system of all of these different elements, and yet my experience of it was Rudolph Giuliani, who had a kind of Mussolini-like desire for power and acclaim, and Bernard Kerik, who was a figure destined to implode because of his own appetites, weaknesses, and frailties. And the O.J. Simpson murder case, which I saw kind of secondhand, coming into the wreckage afterward, was all about the failings of people, or the way human frailty causes these systems to break down.

There’s a relationship between a jury and the judge and lawyers that approaches Stockholm Syndrome or one of those syndromes. Gerry Spence, in Ruby Ridge, was brilliant at playing juries. He would do everything but crawl in the box with them. “You and I all know that this case is insane….” The most brilliant thing that he did in that case—the prosecution put up all of these rifles. All the Weavers’ guns were on this big pegboard. It was daunting, all these guns. At one point, Spence just strode up there and yanked a gun off and sighted it and then handed it through the jury box. The prosecution objected, and Spence said, “Your Honor, they put them up here. I just wanted the jury to get a closer look.” Knowing that an Idaho jury—everyone’s sighted a rifle at some point. So now these rifles aren’t things on a wall. You’d see jurors looking around the courtroom with rifles, and the prosecution going, “Oh shit, we just lost the case.” That was the kind of thing that went on in the Simpson case, too.

I find the anti-government furor today fascinating in so many ways. Because there is no government. It’s us. And in Every Knee Shall Bow, that was the thing I sort of tried to pull back the curtain from. White separatism was another kind of system. Systems don’t battle. It’s the people within them.

LIGON

Do you see common attributes in your characters? Can you look at your characters and say, “I recognize this character as having this kind of moral code or that set of beliefs, or being stuck in this system?”

WALTER

It’s one of those things that can freeze you up if you spend too much time thinking about it. My characters can be wiseasses. They can be a little lost, a little out of step with everything going on around them. But that also allows them to be more observant of paradoxes and ironies and of those moments in which the things that we strive for, and the things that we do, don’t connect. Or, to go back to systems, the things that the system’s supposed to do and what it actually does don’t align.

I think the kind of character I’m drawn to is someone who sees the cracks that other people don’t see, Brian Remy in The Zero being one example—he’s the only one aware of his own condition, which he comes to believe the rest of the world shares but just doesn’t recognize. I think the characters’ awareness of the absurdities around them is the main thing. And then there are obviously some surface things—that they don’t sleep, they’ve all lost an eye, they probably order the same drinks. They riff the way I like to riff. I love Marilynne Robinson’s answer when someone asked her if any of her characters were her and she said, “Oh, yes, all of them.” I think there’s that sense when you create these people that they’re extensions, hopefully not only of you, but partly of you.

LIGON

You talked about fragmentation in Over Tumbled Graves, but there was a different kind of fragmentation in The Zero. Did that fragmentation come early for you in the writing?

WALTER

I had written a short story years ago called “Flashers, Floaters, and Vitreous Detachment.” In that story, there was an insane person who saw streaks and lines and believed the streaks and lines were connecting people and buildings and ideas and things. I had that piece just sitting there forever. When I was at Ground Zero, we kept not finding bodies. We kept thinking we were going to find more bodies and we kept not finding them. The idea that these people were just gone, that they had been atomized, was hard to get your mind around. I kept thinking about that Maltese Falcon idea of disappearing and starting your life over. So I started mulling a novel about someone who disappears and starts life over.

More than any of the other books, that was a thematic book. There were all these things I wanted to say about the culture, about the way we reacted to September 11th, about the leadership at Ground Zero, about all those things that were bubbling around, and yet I couldn’t quite ever complete those thoughts. I couldn’t get my mind around what it was I was trying to say to myself. And I thought, If I wait for this, I will never get there. I sort of transferred my own confusion and inability to track and process to the character. And that felt right. I can’t remember the first time I wrote one of those sentences where I just ended it with a dash, but oh my God, it was the most freeing thing, realizing that you don’t have to write those transitions. Transitions suck. Transitions are almost always forced. Or if they’re not, then they take you—they transition—to a place you don’t want to go.

I had done some screenwriting at that point, and there’s an old saw in screenwriting that you want to begin a scene as late as possible and end it as soon as possible. And I thought, What if I end the scene way before anyone even knows what the scene is about? The freedom of that was a great discovery once I realized I could just bail out of scenes any time I wanted. Sometimes, the scene would accomplish what I thought it was going to, and other times, it would just hang there, a complete fragment. I was aware, all along, of the larger story I was telling, but the fragmentation kept it so fresh for me, because I was never sure how much of it I was going to reveal. I had almost two versions of the story. I had the full story, and I had this fragmented version I was telling. It made me a little crazy as a writer to be walking around with this kind of insane story that I’m telling myself in my head.

LIGON

And that book was also about systems—

WALTER

Part of it is that I’m writing in 2003 and we’re all gung ho to get into Iraq, and I’m writing a book that when I showed my wife, she said, “I think you’ll go to jail for this.” And my agent said, “I don’t think I can represent this book.” But I couldn’t stop working on it.

I went back to Kafka and kept drawing in my mind these lines between Kafka’s systems and the kind of overarching sense in Kafka’s work that the state is bearing down on him, on the individual. And in my mind, this was worse, because we were culpable. We were the system that was bearing down on us. We had a part in it by our inaction, by the fact that we kept electing George W. Bush. We were culpable in the surreal nature of our response to this action. We all knew that we weren’t really going to war because Iraq had gotten yellowcake uranium. We knew that wasn’t the reason. We just wanted to kick some ass. Maybe some of us put little “no war” signs in our windows. And I felt a little bit…I felt as if we’d all gone insane, as if the whole culture had gone a little bit insane. Maybe some of us were only a little insane, but it felt like such a big, important thing to be working on and writing and saying. And from a writer’s standpoint, it was thrilling to be dangling these scenes, and to be sort of nakedly saying things that I, as a younger writer, would not have had the courage to even try to say.