Found in Willow Springs 65

February 13, 2009

Rebecca Halonen, Rebecca Morton, and Shira Richman

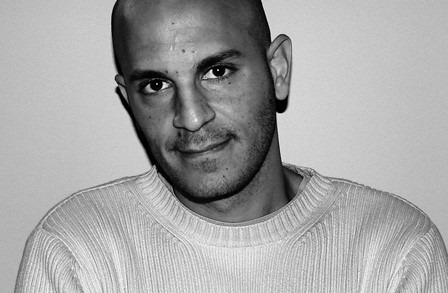

A CONVERSATION WITH FADY JOUDAH

Photo Credit: Poetry Foundation

Fady Joudah was born in Austin, Texas, and currently lives in Houston, but he isn’t generally described as Texan. His parents were born in Palestine and, besides the United States, his father’s career as a professor took the Joudah family to Libya and Saudi Arabia. Fady Joudah continues to lead a life of international engagement. He has practiced medicine in Zambia and Darfur, with Doctors Without Borders, and in what he describes as a “war zone” in Texas, the emergency room of a veterans hospital.

Joudah became well known in the literary world somewhat suddenly when, in 2008, his first book, The Earth in the Attic, was published as the winner of the Yale Younger Prize. That same year, The Butterfly’s Burden, his translation of Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry, won the Society of Authors’ Saif Ghobash-Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation. If I Were Another, Joudah’s second translation of Darwish’s work, was released in October 2009 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

About The Earth in the Attic, Louise Glück writes, “These are small poems, many of them, but the grandeur of the conception is inescapable. Fathers and brothers become prophets, hypothesis becomes dream, simple details of landscape transform themselves into emblems and predictions. The book is varied, coherent, fierce, tender: impossible to put down , impossible to forget. It will make itself felt.”

As a Palestinian-American, and having worked extensively with refugees around the world, Joudah expresses the sense of displacement poignantly, while offering hope through his view of its universality. In his poem “Proposal,” we see the displaced re-placed in disorienting, often alienating contexts: “I think of a little song and / How there must be a tree”; “We left our shoes behind and fled. / We left our scent in them / Then bled out our soles”; and “God reels the earth in when the sky rains / Like fish on a wire.” But it is the constant shifting, which the sea seems to do best, that offers the promise of survival:

And the sea, each time it reaches the shore,

Becomes a bird to see of the land

What it otherwise wouldn’t.

And the wind through the trees

Is the sea coming home.

Poetry, like the sea, offers accessibility to the things most longed for, as Joudah expresses in a piece he published in the Kenyon Review, “In Memory of Mahmoud Darwish,” in which he addresses Darwish: “I would memorize and forget you, tuck you in deep hiding places of my soul, as if I were slowly saturating my being with your seas…sea, that word that also stands for prosody in Arabic.”

We met with Joudah, during the annual AWP Conference, in the Chicago Hilton, where we discussed spiders, playing with time, and “one of the best-kept American secrets.”

SHIRA RICHMAN

I’d like to start with a question about the title of your book, The Earth in the Attic. As humans, our lives revolve around the earth, yet in this book the earth is relegated to an isolated, confined, but elevated place—the attic. Can you talk about how you happened upon this beautiful, strange metaphor?

FADY JOUDAH

It’s a metaphor that comes out of a simile that is in one of the poems in the book, “Along Came a Spider.” As the poem indicates, I happened on it because in one of the refugee settlements where I served, we would wake up an amazing plethora of spider webs after night rain. And spider webs disappear very quickly when the sun scorches them and the moisture evaporates. So it was an amazing scene to drive in the Jeep toward the clinic every morning during the rainy season and see the earth like an attic, in the sense that it was filled with spider webs.

As that poem, “Along Came a Spider,” addresses, it was for me the whole idea that the displaced people of the world, the stateless people of the world, or even the non-citizen citizens of the world—if you want to expand it beyond the boundaries of of governments, nation-states, and refugees—are in the attic. As you say, it is maybe, physically, a higher place. But not in all places is the attic a higher place. In some cultures the attic is a separate room, not necessarily a separate floor as we have in many of our homes. Nevertheless, it is just the idea that you store something you don’t want to throw away, your sense of existence—you store it and ignore it. Only when you move from that house do you check what you left in the attic and see what you want to take with you or throw away. It was that kind of negligence that I was after.

RICHMAN

Were you also thinking about the story of when spider webs hid Muhammad by covering the mouth of the cave and saving his life? Is there something especially treasured about spider webs?

JOUDAH

What interests me is: How does one divert his gaze to nature, without addressing nature as something separate from what we call human progress? Living where I was—I don’t like to name the place and I’m going to get to that—we were surrounded by spiders and other insects. You live comfortably with them. If you see a spider in your house, you don’t call the fire department. So I found myself roommating with spiders or living with spiders and that sent me to the childhood story about Muhammad and then to ideas of identity and spirituality and religion. And that also sent me to another concept, which is the very distinct reality that an Arab or a Muslim in the English language is and has been persistently dehumanized, really.

I say this with particular care, not to necessarily make that identity holy by virtue of an absolute sense of victimhood, because no victim is necessarily a saint and there is no such thing as a race of victims. But I do think there is an arc in the poem that tries to address the humanity of the name, beyond the jargon of history. There’s also a particular slippery slope in the poem I’d like to address about revolutionary ideas in general. I was trying to create, revolutionize, introduce the concept of displacement of the refugee as that which sends us into a new era of hope and “progress,” because it is that sense of horror as byproduct of the nation-state that will probably get us past this limitation of the nation-state and its concept of citizenry and so forth.

In a sense, all religions, when they arose, were modern, revolutionary; they broke with the past, and they advanced the people that initially jumped on the ship. They advanced people, whether or not they were monotheistic. Then myths and traditions and rituals take place. I went far to try to reengage the concept of modernity through the refugee. It’s a bit problematic because if you are a refugee or a stateless person or a displaced person, it does not necessarily mean you are some form of saint, whatever that means. But I think we don’t have enough recognition of the victim as a victim first and foremost. And there’s always a tendency toward apologetic that end up dehumanizing victims more and more.

REBECCA MORTON

Yesterday, at your reading, you mentioned that you work to not abstract people’s suffering.

JOUDAH

I think we all walk around with a filtered vision of other people’s suffering, and naturally we cannot preoccupy ourselves with it too much if we are going to go on with our daily lives, nor should we to a large extent. But I think that people’s suffering becomes a matter of image-intensive desensitization. I think this is particularly the case for us in the U.S., because we are among the five percent of people in the world who have access to the Internet, to movies, to the digital age, and so forth. We think this access is actually the norm, because each of us has whatever phone we have that we can’t operate and laptops and so forth. I see the importance of universalizing suffering. One does not necessarily need to carry the banner of each trauma in the world to at least remain cognizant that suffering which plagues us all is really in large part a product of the abstraction of some people’s humanity and not others’.

Some people are seen as fully human, so their suffering is something we connect with and make holy, and other suffering is just racialized or what have you. There is—I think in Darfur—a stunning example of an entire movement that was and still is obsessed with naming the atrocities, and it is unfortunate because it does nothing for the people of Darfur. Even if the naming stuck, it would still do nothing for the people of Darfur. What remains of that “game of the name” is basically racial politics. I was shocked about this because I was there and suffering was far beyond the pettiness that we think of in our important intellectual skin here in the U.S. We’re always the interventionists; we’re always the ones who are able to do something about things. But the suffering I witnessed was beyond all this jargon.

Theodor Adorno wrote in his Minima Moralia something called The Paragraph. You won’t find it in all editions of Minima Moralia, but there’s a section in the book Can One Live After Auschwitz? called The Paragraph, and he basically talks about the term, the aporia, the paradox, or the unsolvability of naming something and what happens to the name, and he was specifically referring to the UN charter on genocide. It’s a fascinating precedent in the ’40s—around sixty years ago—about how this whole idea of naming genocide will eventually turn into a game of names. After what point does suffering on a mass scale deserve no name and become something that has to be addressed, or at least recognized, by everybody?

I go back to the concept of the universality of suffering. The answer to this for some people is: Well, we’ve decided in international law, which is an important thing if it is at least adhered to and approved—and that is nor the case—that if it’s genocide, we will intervene. The game of the name is to do enough to where those who know how to play with the law—whether they wrote the law or know how to play with the wording—go far enough in their atrocities not to have it called genocide.

So what happens? Ethnic cleansing is, in many people’s minds, an early stage of genocide. So do you not intervene there? What about civil war that is so horrific in its detail, in the Congo, or in Angola when they had their civil war, or in Sri Lanka, or in places that didn’t have civil war—what the Indonesian government did in East Timor? How can you claim that there is a holiness of suffering more important than another or even a legality of suffering? How can you turn such massive suffering into a classification? And whatever answer you give, we have enough history to show us that we know what happens with the politicization of suffering. It dehumanizes the victims repeatedly.

I’m not necessarily saying that we should reduce our threshold for intervention. I’m not necessarily sure that the word “intervention” is the modum operandum here for me, but I think what interests me the most is: Are we truly willing to recognize, first and foremost, suffering, without gaming the name? And then, if we get to that point, what happens afterward? Because I think it would be, hopefully, a brighter moment.

REBECCA HALONEN

How do you understand the role of a poet in all this? What is the poet’s duty?

JOUDAH

I don’t think that writing the poems themselves has to address these issues necessarily, but I do think that one has to be engaged, as a whole person, with such things, to be open to them and courageous enough to recant one’s errors of judgment regarding a larger humanity. I say these words as though I’ve reached this state, but I’m very far from it.

I can’t say that poets should do this or write that. It’s an art form; it’s an imaginative state of being that dabbles with time, and it cannot necessarily be limited to certain concepts. There’s a lot more to poetry and art than the drama of American family life or the politics of refugees. There’s room for both ends of the spectrum, I think.

Bertrand Russell engaged himself as a literary man and a morally committed person. For instance, many of us don’t know that the Russell Tribunal (after Russell’s death) for human rights declared the U.S. action in Vietnam to be genocide. And here’s a man who was celebrated in the English world and the Western world and the world over, won the Nobel Prize and whatever. It is not necessary to say that the U.S. has to be punished or not punished. I’m not even getting there. All I’m saying is that the Tribunal’s declaration should be recognized. Again, until we recognize such things, morality becomes a political game.

A poet should be engaged wholly with such morally difficult questions, being very careful and aware of the slippery slope of proximity to power. You don’t want to raise a banner. We can all get a little too passionate and find out twenty years later that we actually got a little too intense about an ideal or an ideology and ended up as fascist as those we were professing against. But we do have examples of people like Bertolt Brecht or Walter Benjamin who were Marxists and had no trouble backing away from Marxism, when it stood as a political regime they recognized as a problem.

A poet has to be fully engaged, but also has to be careful of the dangers of ideology. I think a poet should struggle for a form of moral and cognitive independence from the jargon of politics or history.

HALONEN

Do you think political poetry is attempting to do that?

JOUDAH

I don’t like the term political poetry. I think it is demeaning, and probably a reflection of certain problems within the literary canon and its relationship to power establishments. It’s convenient to call something political poetry, because it seems to deflect how the poetry establishment itself is deeply embedded, naturally or otherwise, within the larger political system of power, and I think it’s essentially a description as full of hot air as truly propagandist poets are.

There is no such thing as political poetry and non-political poetry. There’s good poetry and bad poetry. Whether good poetry happens to be about your dog or about war—it doesn’t matter to me. But anyway, there’s good poetry. And good poetry is not simply defined by form and theme. There’s a larger human engagement that should be addressed within it.

MORTON

You touched on this before, but I’d like to return to naming. There are no place names—or very few place names—in your book, and because of this, I think the reader is a little unsure about how to inhabit the poems. It feels a little like we, as readers, not being placed, are in a sort of exile. I wonder about exile and the position of the outsider in the poems.

JOUDAH

I have to answer in two parts. I think that refusing to name the place is because of the tendency toward sensationalizing the locale, and that distracts from the suffering and the humanity of others. People refer to Darfur in my book of poems, and I insist on not mentioning which parts of the poems speak of Palestine and which speak of the Congolese and Angolan refugees I took care of in Zambia. But it’s interesting that some people feel a particular sense of comfort in mentioning Darfur, and that’s their problem, not mine.

There’s a lot of stuff that merges with so many other states of being. I hated the idea that people would say, ” Did you hear what he wrote about in Zambia?” And it’s not necessarily about Zambia. It’s about the human condition.

There’s no doubt that identifying myself as a Palestinian rubs many people the wrong way. The information is also utilized by people to ends I’m not interested in whatever those ends are. You mention the word “Palestinian,” and you get people standing on either side of the aisle. I’m not interested in that in my poetry—maybe in some other arena, but not in my poetry. Sometimes it’s comical to me to hear the commentary or to read reviews because some people are trying to dabble with how to make sense of political views in the book. Actually, what they’re trying to do is make sense of their own political views or lack thereof, not necessarily the poetry that I’m trying to write.

As for exile, I think it’s the state of the poet, period, whether it’s internal exile or external exile, and in most cases it’s both, which I think is also a state of the human condition. I think we all feel internally exiled from ourselves or even our loved ones. You wake in the morning and you’re tired of going to work. You put on a particular persona when you’re at work, and it’s different when you’re at home and it’s different when you’re with your mother or your father or your wife, husband, and so forth. Sometimes the pressures of life make you feel like you’re far from who you think you are or who you aspire to be or all these things that we grapple with in modern day psychology. Then there’s the external exile, which goes back to the original point that I mentioned—the idea of one of the syndromes of our contemporary existence: What does it mean to be a citizen?

MORTON

I read that you began writing during your residency. What was it that you wanted or needed in poetry during that time?

JOUDAH

Chinua Achebe said something about how you write because you have a story to tell. I have a story to tell; I could have written novels or I could have written essays, but why did I write poetry? I don’t think anyone knows how to answer that question. I just think it’s some little twist in the brain, that I’m inclined to the rhythms and patterns of poetry as opposed to other methods of linguistic expression.

HALONEN

Do you write in Arabic?

JOUDAH

No. My relationship to Arabic has become quite automatic. There are many instances where I am probably writing something in English directly from Arabic, not being conscious of it at the moment, but when I put it down on paper I realize exactly where the syntax came from, exactly where the automatic translation process came from.

RICHMAN

Why don’t you write in Arabic?

JOUDAH

Because I exist in English, I guess, for a large part—as far as writing poetry. In reaction to that, I chose translation from Arabic into English to maintain a relationship to Arabic in poetry. But I have a busy life as it is—as a physician, a father, and a husband. I’m trying to write, I’m glad to be writing. I’m writing and so I’m happy about that. I don’t want to put too much emphasis on linking my identity to the language that I write in, as if it’s somehow part of a political statement or a cultural statement. I’m glad to be writing poems when I can.

HALONEN

Can you talk a little bit about the opportunities or limitations of translation?

JOUDAH

Translation is a mistreated aspect of poetry. I think all poetry is translated. Perhaps all life is translation, since we consider reality as a matter of perception, and so is our perception of our own reality through language. It comes across as a translation. At least in creative writing as opposed to the hackneyed speech that we all share over the air and whatnot. So that is one aspect of it.

The other aspect is that the actual process of taking work and writing it in a new language gets a bad rap in the sense that the concept of fidelity is, I think, prostituted by even the best minds. Because there is no such thing as infidelity and there is no such thing as fidelity. All forms of translation suffer from fidelity and benefit from it, and suffer from infidelity and benefit from that. Those who say, “Well, you should try to make it seem as much of a natural poem as in the host language,” are after fidelity in a different way than those who say, “No, you should be strictly accurate and representative of the original language.” They’re after a different kind of fidelity. Or a different kind of infidelity. Freud would be happy with this.

What’s most important for me in translation is the transference of the spirit of the text. If I translate poetry five or ten years from now, I might have a different opinion, because I think my relationship to language changes as I learn more and have different opinions about it and so I approach things differently. I do think translation should attempt to infuse something new in the host language, so it allows for that sense of mystery to exist, as opposed to those who want a natural poem in the host language—whatever that means, because “a natural poem” has its own problems. The host language has a wide array of “natural poems.” I think Celan said, “There is no such thing as translation. You write a new poem.” I disagree with him, because my poems take a lot longer to write than it takes me to translate. But that’s not what he was talking about. I think he meant that if you’re infusing something, you are writing a new poetry, introducing a new poetry.

RICHMAN

You seem to use rhythm deliberately in your work, and in many places I’ve noticed a symmetrical meter, most obviously in the titles The Earth in the Attic and The Butterfly’s Burden. When scanned, they have identical rhythms. There’s symmetry in many parts of the poem “Pulse”—in section seven, within the line: “One of us shouted Wow in her sleep,” and between the lines of the last couplet of section nine: “Then saplings and mud. / And then the dried sand.” How deliberate are you in determining your rhythms?

JOUDAH

Not very, at this point. I used to count syllables a lot, and not for lines. I counted them sometimes for sentences, and sometimes, in shorter poems, I counted them for the totality of the poem. But not per line. I do like the focus on a deliberate rhythm, as you call it. And I also do like occasional merging between classical prosody, if you will, and a contemporary sense of rhythm. But I go a lot by my ear, knowing that poetry is largely dependent on normal speech, whatever that means, and on normal speech patterns, which are varied.

There’s an interesting concept in formal contemporary Arabic poetry, similar to what I said, where the unit for prosody, which is called taf ‘eelah, is basically in the entire poem or in the entire stanza, so it’s not dependent on a line. And I was always interested in this way of looking at the whole poem. That goes back to why I used to count syllables in the entire poem. If I had an even number, I considered the poem metrically complete. But that’s obviously not true, because you can also have an odd number and it all depends on whether you use an anapest or a dactyl or a trochee and, again, it goes back to speech patterns, so it’s not fixed. But it is a whole idea that in the sentence, in the stanza, or in the entire poem, there is a sense of complete foot count, if you will, a complete meter of sorts, without the focus on line-per-line symmetry.

RICHMAN

I don’t know if I’m imagining this, but in “The Onion Poem,” is there a glimmer of a ghazal?

JOUDAH

I remember sharing that poem with Marilyn Hacker, and she said, ”I’m glad to see you’re making your own form of a ghazal.”

I don’t like the ghazal form, though, to tell you the truth.

I don’t disparage it at all, but somehow it just doesn’t appeal to me. I like repetition in poetry, and I think poetry is dependent on repetition and parallel, but I’m not into that form. I guess you could say if the idea in “The Onion Poem ” is to repeat the tone of question—the repetition of question and answer, which is an ancient idea in poetry—you could say that it parallels the ghazal in that sense. I guess “The Onion Poem” presents its own dialectic in the first question and resolves it, seemingly, in the answer, in the reply. But then again, if I say that, I am not paralleling the ghazal line; I’m just paralleling an ancient method of call and response in poetry.

Formal elements in poetry, especially in free verse, are wonderful when they go past that idea of metrics and numbers, because there are so many aspects of language that lend themselves to formality, whether regarding alliteration or anaphora or epiphora or parallelism or chiasmus. All these wonderful tools, for me, are what make the free verse poem formal.

RICHMAN

In the poem “Proposal,” the sea becomes loosed from its seabed and becomes a bird. It becomes wind, which allows it to see aspects of land and to know the trees as home. To what extent do you identify with the sea?

JOUDAH

I don’t know. I feel a little emotional to address the question. It’s a trope. The sea is a trope. I guess I can hide behind that in my answer.

RICHMAN

I was wondering if you were referencing the fact that the Mediterranean Sea dried up at one time and then somehow returned to its place?

JOUDAH

If I engage in this conversation, I’d be analyzing the privacy of the poem, dragging it out into some sort of a factual discussion, and I think that would take away from it. For me, it’s important that readers see and hear that sea the way they wish—as the Mediterranean or as the sea you hear in the air when you’re far from the sea. I’m also aware that some people don’t know what to do with the mention of the word “Haifa,” for instance.

I’m addressing my wife and her father and my father. But really, the poem was written far away from the past and the Mediterranean. I can tell you that much.

MORTON

In the book’s first poem, “Atlas,” the speaker says, “Let me tell you a fable.” This sort of storytelling appears throughout the book. Why?

JOUDAH

I don’t have a spontaneous inclination toward a full narrative poem, but I think narrative is essential to poetry and to the contemporary poem. To incorporate it, I have to wed it to lyric. Some people have a rash about the concept of “lyric narrative,” and some people are puritans—either there’s a lyric poem or a narrative poem. I guess I believe in that merger, or that unity.

I have a tendency toward playing with time. Narrative means that there is a chronological order, or disorder, but I try to incorporate lyric into my narrative so that the narrative appears to be from within my time and from without it. Some people might use the word “legend” or “myth” for that, and for me, much good poetry comes out of the attempt, the successful attempt, to rewrite myth.

But what is meant by myth? Is it the sublimation of a ritual? And I mean sublimation in the way solid goes into gas, that chemical process. So you take a ritual and you somehow release it of its own physical properties through the language of time. Whatever that means. In interviews you have to say, “Whatever that means.” You have to include these disclaimers.

HALONEN

Which poets do you return to?

JOUDAH

I think it varies in different phases. I used to go back to Rilke, but I don’t look at him at all now. These days I go back to George Oppen. I love his lyric. I think he’s an incredibly engaged poet with the world and has a wonderful sense of humanity that pierces through ideology. A light with luminosity. You can see there’s something magical about his abandonment of poetry. He quit poetry and then twenty-odd years later he returned and had a very prolific output in his older years. Through those years you see how he progressed with his syntax. Or not how he progressed, but how he varied and experimented with syntax and lyric. It’s refreshing to see this engagement with the world in his actual life and in his poetry while still being true to art itself—instead of getting lost in ideologies.

He’s one of the best-kept American secrets. There is a rise to his name now because we are in a state of war. Which I think diminishes his brilliance. This brings me back to political poetry—a lot of people consider George Oppen a political poet, which for me is just absurd. Maybe it’s similar to how people get all worked up about the term “confessional poetry.”

RICHMAN

I read that when you were seven, you were watching television, and you announced to your mother that you wanted to be a doctor. What were you watching?

JOUDAH

I don’t know. I know there was a family gathering—my aunts and cousins and so forth—and we were in Libya at the time. It’s a question we all know—everyone turns to you when you’re younger and says, “What do you want to do when you grow up?” I don’t know why I said I wanted to be a doctor.

I must have been overwhelmed by some sense of…I was thinking about it this morning actually, and this is a way to address the restructuring of memory. This morning I wanted to say that I must have felt some sort of angst in the room or in the family situation. Something must have happened. My family—my immediate family and aunts and uncles and my older cousins—are all refugees in the true sense of the word. They had rough childhoods. I don’t know if some of that sense of anxiety was somehow seeping in the conversation and I picked up on it and decided that I had to say something or whatever. I have no idea.

RICHMAN

When did you realize your interest in poetry?

JOUDAH

Probably around the same age, because I used to memorize a lot of poetry when I was younger and recite it and get encouragement and support for such memorization. I started to write random lines— three- or four-line poems or something in Arabic prosody. So I think I’ve had that interest since a young age, but there was all this side-tracking, with the medicine and leaving one culture and coming to the next. Eventually, I realized I just had to keep writing. I had to keep expressing my own existence.