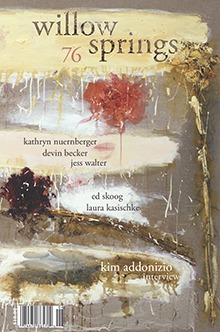

“Cheston!” by Jess Walter

SOMETHING WAS THE MATTER with the baby.

“He seems depressed,” said the father.

“I don’t think babies can get depressed,” said the mother. She suspected Cheston was mimicking the father, who sometimes affected the sort of spiritual weariness blues players exhibited, or aging gunfighters.

“Anyone can be depressed,” the father said defensively. He wondered if the mother calling Cheston the baby wasn’t the real problem; he was, after all, nearly four. The father decided to start calling him Buddy.

Cheston was playing Legos. The father walked over. “What are you building, Buddy?”

“Gallows,” Cheston said.

The mother tried to sound cheerful. “Who are you hanging?”

“–Buddy–” the father added.

“Hope,” Cheston said, the Lego man twisting in the still air.

“HOW ABOUT THE TRAMPOLINE PLACE for your birthday?” the mother asked.

Cheston was coloring. He only used the one crayon: black.

Sponge Bob, Squidward, Patrick, he was coloring them all black. “I don’t care.”

“We could have the party here.”

“Doesn’t matter,” Cheston said.

“Who should we invite?”

“Mother.” Cheston dropped the black crayon in the crease of the coloring book. “I. Do. Not. Care.”

“But it’s your fourth birthday,” she said.

“Yes. I am aware of that.” Cheston’s blonde hair swooped in a curling C on his forehead and his eyelashes batted like waking butterflies. Finally, he sighed. “Maybe Cameron-“

“Cameron, yes!” the mother said.

“Because I hate Cameron.”

“Why would you say that, Cheston?”

“Why would anyone say anything?”

SOMEONE WAS NICKlNG THE FATHER’S SCOTCH. He drank only pricey single-malt! slays- Laphroaig, Ardbeg, Bruichladdich. The father suspected their housekeeper. The bottles were kept in a series of tall cabinets in a big closet off his study. The father had just decided to mark the open bottles with a Sharpie when he saw something under one of the liquor cabinets.

A sippy cup lid.

The father walked to Cheston’s bedroom doorway. The boy had his back to the father, facing the window, and was palming his Batman sippy cup like a brandy snifter. He swirled the drink. Ice clinked.

The father was dumbfounded: who puts thirty-year-old scotch on rocks?

THE PSYCHOLOGIST REMOVED HER GLASSES. “Well, technically, there’s nothing wrong with Cheston.”

The way she said “nothing wrong” made the father think that having nothing wrong might be the worst thing that could be wrong with someone.

“We did standard testing, associative play. Cheston’s a bright boy, as far as that’s concerned.” The psychologist looked over the frame of her glasses. “And there’s been no recent trauma?”

“No,” they both said too quickly, without looking at one another. They lived well, in nine rooms on Central Park West. The father had inherited a great deal of money and his “work” was managing his own wealth. The mother volunteered at charities.

“We should be careful,” the psychologist said, “trying to diagnose what might just be a reasoned belief system.”

My son is Jeffrey Dahmer, thought the mother.

“What I’m saying…” the psychologist took off her glasses, “… is that I don’t think Cheston is depressed. I think… ” she chewed her lip, “… your baby is a nihilist.”

*

AT HALFTIME, Cheston’s soccer coach pulled the father aside.

“Listen,” the coach said, “I appreciate Cheston’s unique personality, but he keeps shooting at our goal.”

It was true. Cheston’s condition had progressed to mereological nihilism. He no longer believed in the composition of things. For Cheston one goal post was just like another, in fact was no different than a telephone pole or a doghouse.

“Maybe play him at forward?” the father suggested.

In the second half Cheston no longer observed the random nature of sidelines. He dribbled through the parents, to the next field over, and booted the ball into the street.

“Good kick, Buddy!” yelled the father.

“MONKEY SHOESHINE LUMBER TRUCK, ” Cheston said at dinner one night.

“What?” his mother asked.

“Balamagafu,” Cheston said. Then he made a farting noise and stabbed himself in the leg with his fork.

While the mother put him to bed, the father looked it up online. “Epistemological nihilism,” the father said. “He’s denying the

validity of all knowledge: language, ritual, it’s all lost meaning. He’s given into complete abstraction.”

The psychologist said to bring him in on Monday.

The mother gripped the phone. “What if Monday’s too late?”

“Toddlers are incapable of that,” the psychologist said. “Of harming themselves.”

But that hadn’t even occurred to her. The mother was afraid of something else.

THE FATHER CAME OUT of his study, holding in one hand Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and in the other Heidegger’s Nihilism as Determined by the History of Being. “This is interesting,” he said. “If we can get him to differentiate between being and A being… then maybe… maybe…”

Low clouds raced past the window. The mother sighed. “I’ve had a lover for two years.”

“Me, too,” the father said. “For almost four.”

“And you’re gay,” the mother said.

“Yes,” the father said.

“I turned tricks in college,” the mother said. “I didn’t need the money. It was probably the last time I was happy.”

“I’ve never been happy.”

“I know.”

“I embezzle money from my sisters’ accounts.”

“I hate volunteering. I despise the poor.”

The father searched for something else to say. “I wear your underwear,” he said finally.

“Yes,” the mother said.

The father held up the Heidegger book. “I don’t understand a fucking word of this, Cecilia.”

The mother began weeping.

Because her name wasn’t Cecilia.

“Buddy!” the father cried.

“Turkey shoe blindfold,” the mother said. But even as she said it, she couldn’t remember what those words meant.

The father yanked down his pants and his wife’s underpants. He peed all over the marble floor.

“Happy birthday,” Cheston said from the doorway.